Places in the mind - online exhibition

Places in the mind

With: Peter Black, David Cook, Chevron Hassett, Harry Culy, Mary Macpherson, Jane Wilcox

PhotoForum Online exhibition: October 2021

Curated by Mary Macpherson and Harry Culy

Essay: The Marzipan Tree, by Mark Amery for PhotoForum

(Peter Black, from Blacksville, David Cook, John, from Social Housing, Chevron Hassett, from One Heart, One Beat, Harry Culy, from Mirror City, Mary Macpherson, from Of the Hill, Jane Wilcox, from Māhina)

I

There was the box of marzipan I stole from the larder. I hid it out of sight in a hollow tree, just over the hill from our house, in the strip of bush lining the edge of the river estuary.

When I think of this place the light is always dappled, the sun shining through the leaves. There’s a soft bed of leaf fall underfoot - lace-like skeleton leaves - and, out beyond the darkness of the bush, bright light glints on shell and water. There’s the sound of the clicking of small crabs, and the smell of warm rich earth on my fingers. I’m there for a twist of sweet from the disappearing marzipan bar. Over time, its box sinks deeper and deeper into the dying tree until finally one day my arm can no longer reach it. I have lost it for good.

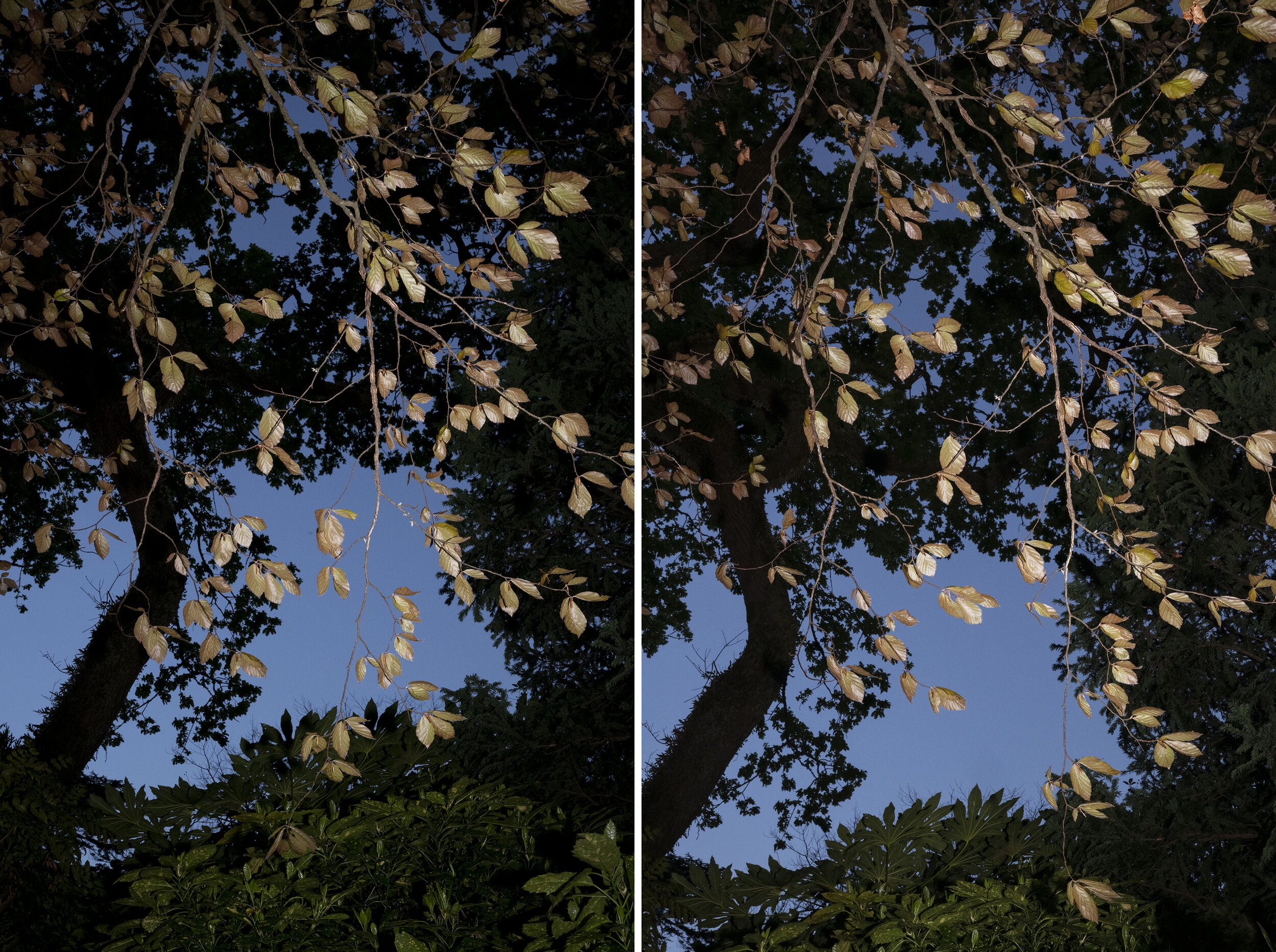

(Jane Wilcox, from Māhina)

It’s one pin in my memory map of a childhood landscape in Okura, on the northern edge of Tāmaki Makaurau. It’s the landscape that existed just beyond calls to come home for dinner. From the vantage point of the family house deck it stretches out of sight in both directions along the river, in bush and on mudflats, under and in branches of trees.

As I walked away from the house, glancing over my shoulder to see if I was spotted, I crossed an invisible boundary. Free, yet within a stumble of familiar houses. A space for personal invention; for stories, play and discovery - of all kinds - with friends. Each small bay or turn of path here in my mind still has its own warm psychic shape, its outline sharpened by danger: the soft mudstone rocks we carved the names of our girl crushes into with the broken bottle glass found in the cracks (itself slowly softening with the wash of the tide); the little dilapidated shed where we discovered cigarette butts and tried to smoke rock oysters; a giant stand of bamboo where we made a hollow and stashed Playboy magazines taken from my friend’s father’s wardrobe.

From age 7 to 19 - child to teenager to adult - my body grew bigger in this landscape. The world beyond it was a differently scaled place. Now I am of that wider world, and this first mapped land seems smaller. But I hold it in my mind’s eye. It remains close.

This was a liminal landscape: a space between family and a shared wider world, between one destination and another, which I was yet not able to fully visit. There are things in that land I’m not proud of. Small things - representing negative aspects of developing small pockets of life for yourself - but it’s also a place I discovered to be both in the world and with myself.

Now I have other liminal landscapes that exist between my home and the wider world, but the potency of those childhood memories sees their aura mapped onto these new places. Is this the case for all of us? I have now lived for even longer in Paekākāriki, home of hapu Ngāti Haumia, than Okura. A landscape bound by maunga Ngawha, awa Wainui and te moana. Across this, are pathways through the sandhills, tracks created as much by people as planners.

II

We are bound to the landscapes just beyond our fences far more than our legal rights over parcels of property indicate. Or capitalism encourages us to believe. I take the spirit of this from the words of Frank Lloyd Wright in the frontispiece to Mary Macpherson’s series in Places in the Mind : ‘a house should not be on a hill but of a hill.’ It is, as Lloyd Wright goes on to say, a matter of belonging and - my words - not ownership. Just out of sight and call are familiar and very personal topographies more widely treated as banal, almost invisible. They provide spaces for our minds to roam between our arranged selves and a more uncontrollable wider world. In the mind’s eye they are in a way both interiors and exteriors, mirroring the interior chamber of the analogue camera.

(Mary Macpherson, from Of the Hill)

Together the works in Places in the Mind create their own collective liminal landscape of Te Whanganui-a-tara, Wellington. There is Blacksville but there is also Mirror City, and other unnamed but psychically mapped locales. The mirror I hold is different to the mirror you hold, but they reflect some of the same spaces in a small city. These are important shared places. We just don’t often notice. Or read about them, or see them portrayed.

In Places in the Mind photography free ranges through this terrain as shared between photographer, subjects and viewers. It can even be, in the case of David Cook’s Social Housing, an apartment block elevator. Where in those shiny-surfaced enclosed in-between spaces - their own mirror cities - do our minds go? Light bounces back at us.

(David Cook, Newtown Park Apartments IV, Danny, from Social Housing)

The preciousness of psychic spaces within our close environs is more commonly discussed in regards to mental health and gardens. In her 2021 book The Well Gardened Mind (pub HarperCollins) psychiatrist and gardener Sue Stuart-Smith writes of the garden as the space between our dreams and the ground - the place between what is ‘me’ and ‘not me’ and ‘between what we can conceive of and what the ground gives us to work with.’ Yet the landscape of these photographs and of which I write is beyond the garden fence. It’s more dangerous. It is shared, yet also gardened by the mind. For many people it's all they’ve got.

My remembered idyll is rural, for others it’s the odd out-of-sight scraggy corners of rubbish and weeds in suburb or city. Places neglected by urban design and the council worker’s care. In Wellington you may be lucky like Macpherson to have the town belt. For others, as in Culy’s suite, scraggly pockets of streetscape or back carparks are valued space.

With Places in the Mind we can create a different kind of map of Wellington, far from the touristic or standard documentary viewpoint of Wellington.nz.

(From left: Peter Black, from Blacksville, Harry Culy, from Mirror City)

In the 1970s geographer Jay Appleton developed a psychology of the landscape based on the belief that we prefer environments that have elements of both ‘prospect’ and ‘refuge’ - places where we can see without being seen, but also that provide places to parade. I’m reminded of the behaviour of birds outside my window. We look for vistas but we also look for protection. Space to be creative, yet open to happenstance - space in between places offering cover and display. It’s here we might find this exhibition.

Co-Curator Mary Macpherson uses the term post-documentary to describe this grouping, and it’s true that one thing that distinguishes this group is the way narrative and truth is left up to us as viewers. We make our own paths, mould our own trees. Places in the Mind is more akin to a web containing different angles, refusing to take one story arc or perspective. I take Harry Culy’s image of a web between side mirror and car body as some emblem.

Equally, the artists are in no way one school. They are quite different from one another, while all deeply engaged socially and politically with the world around them, playing in this space between ground and imagination. The viewer is an active author. Just as with platforms like Instagram we make our own meaning through a patchwork of images, and the fracturing of any sense of a collective truth in the media leads currently to the fledgling concept of post-journalism (as proposed In Andrey Mir’s 2020 book Postjournalism and the death of newspapers).

III

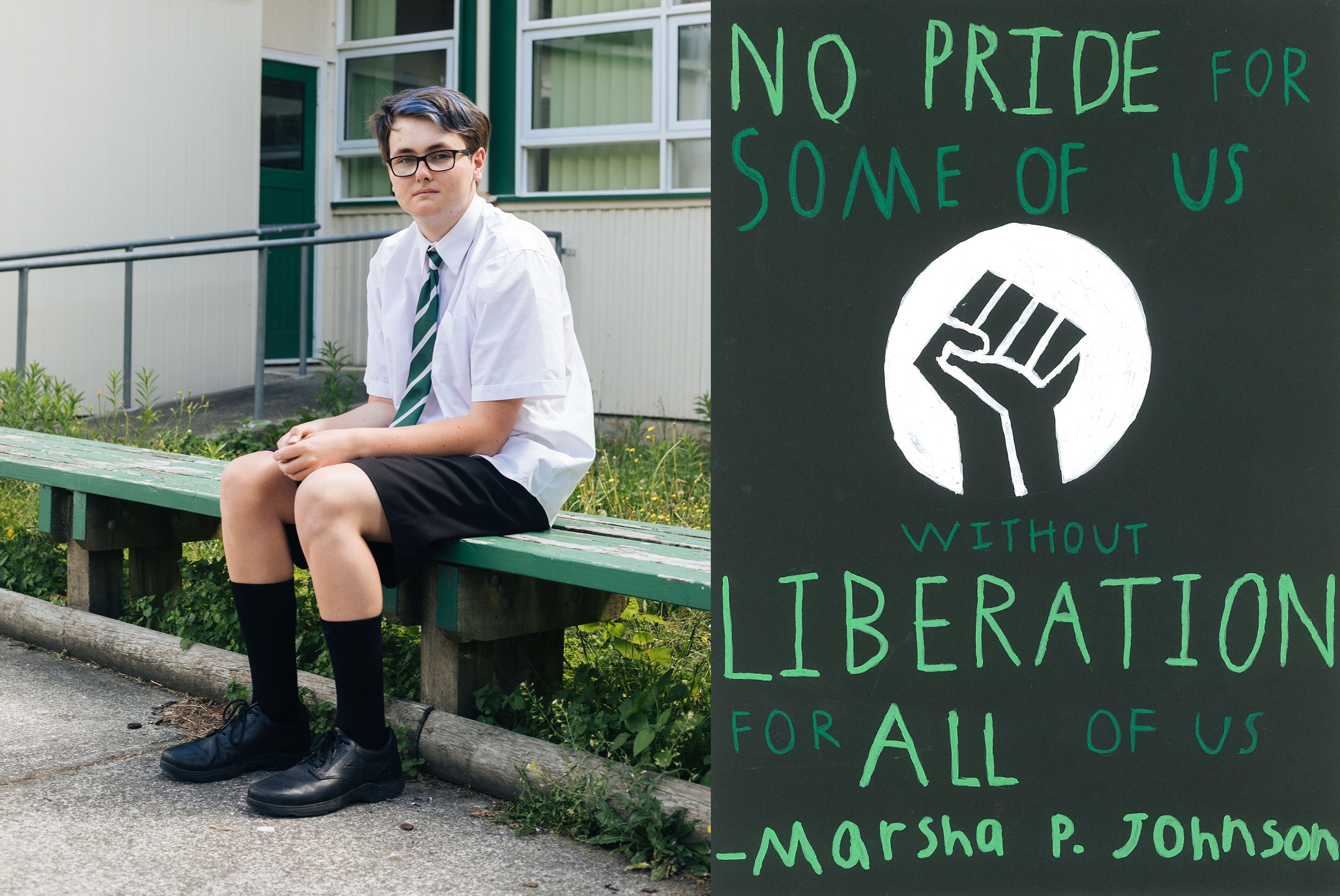

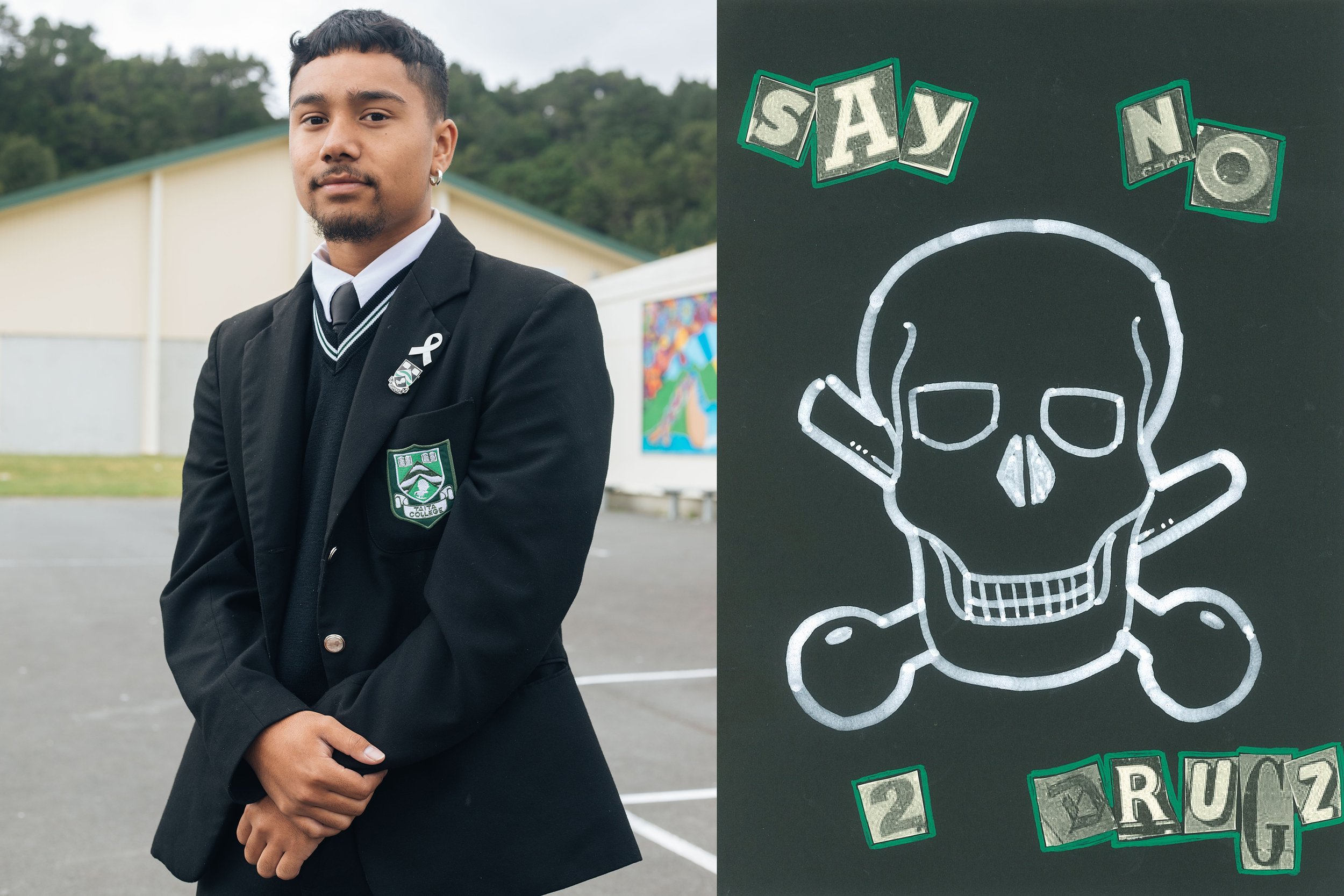

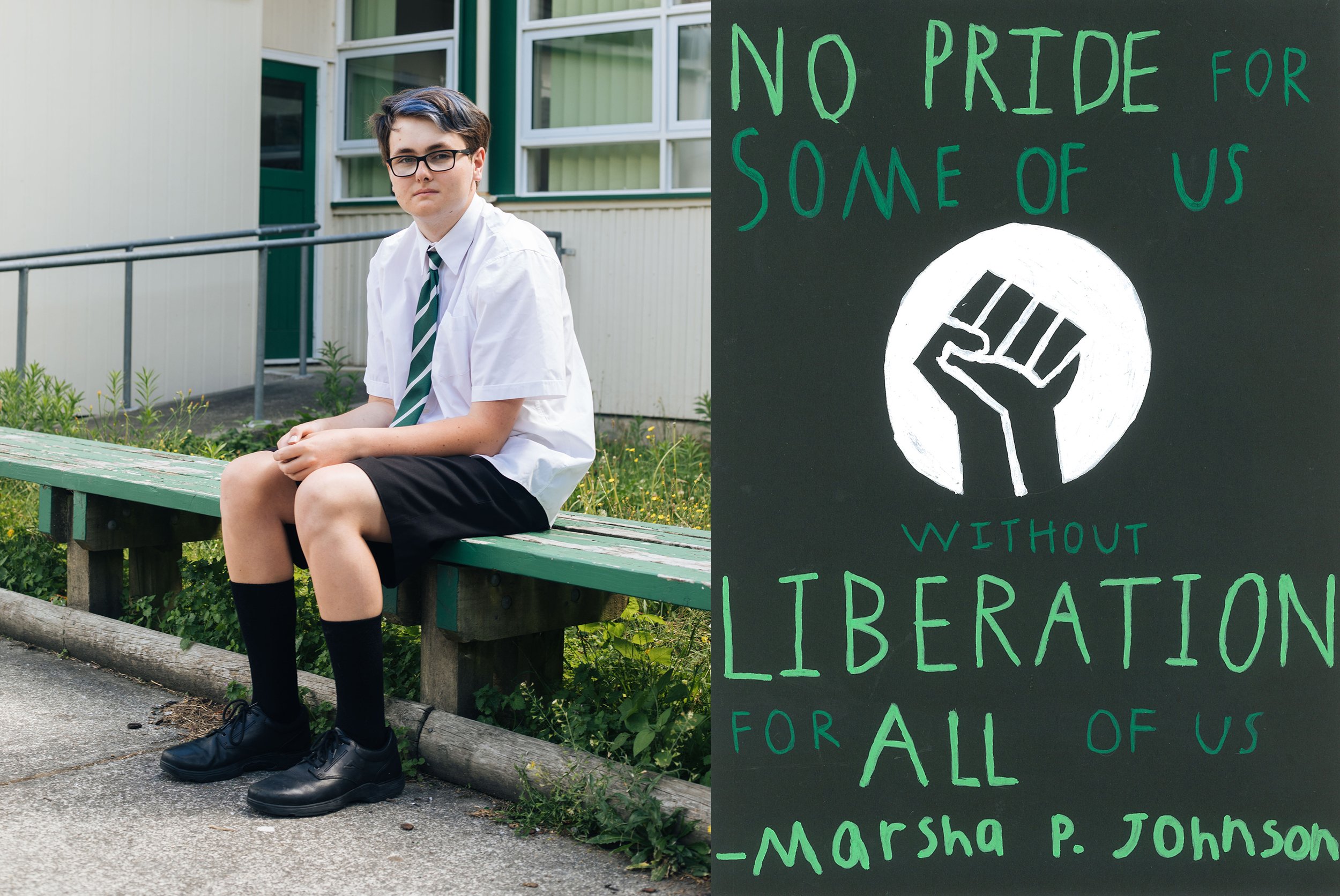

(Chevron Hassett, from One Heart, One Beat)

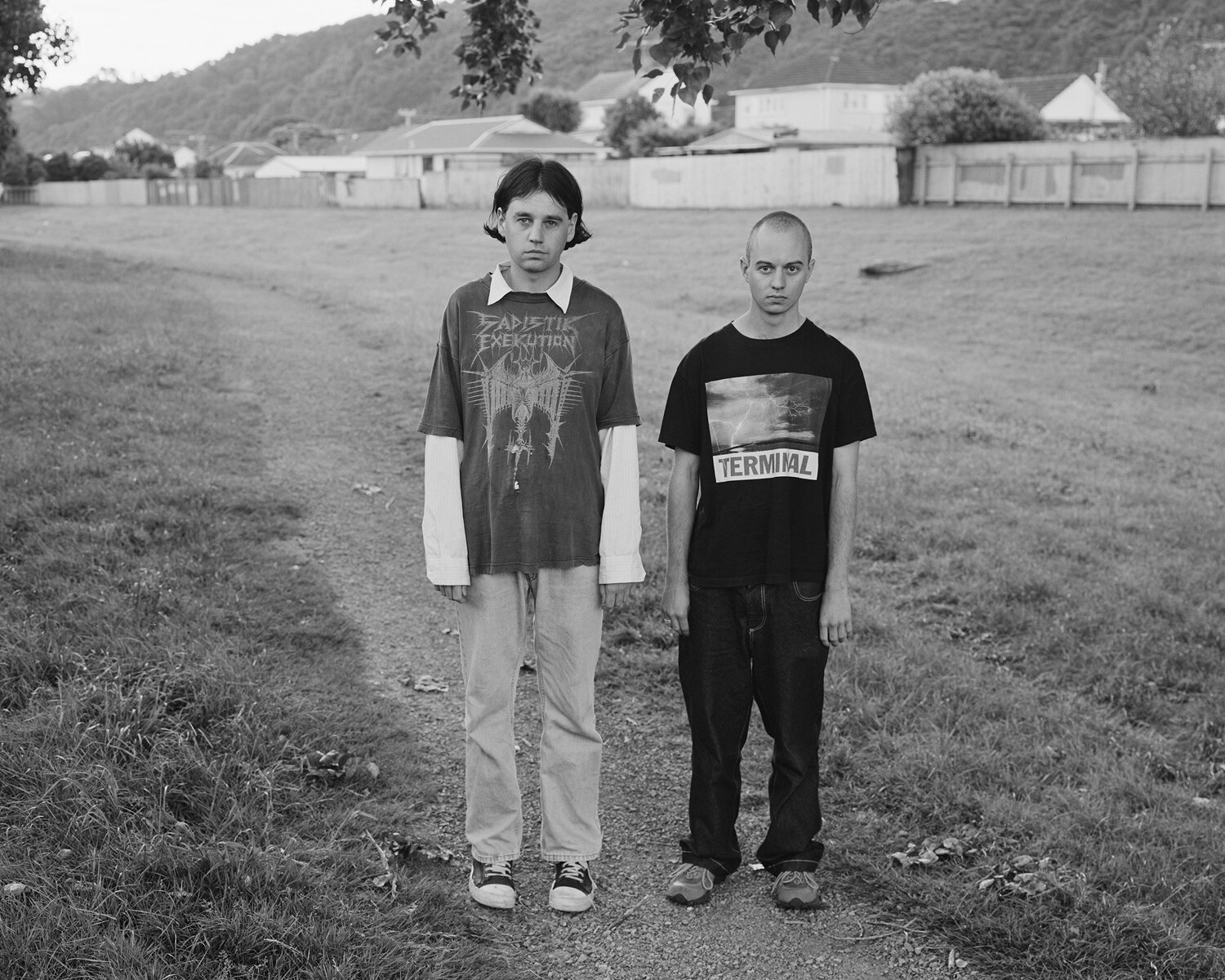

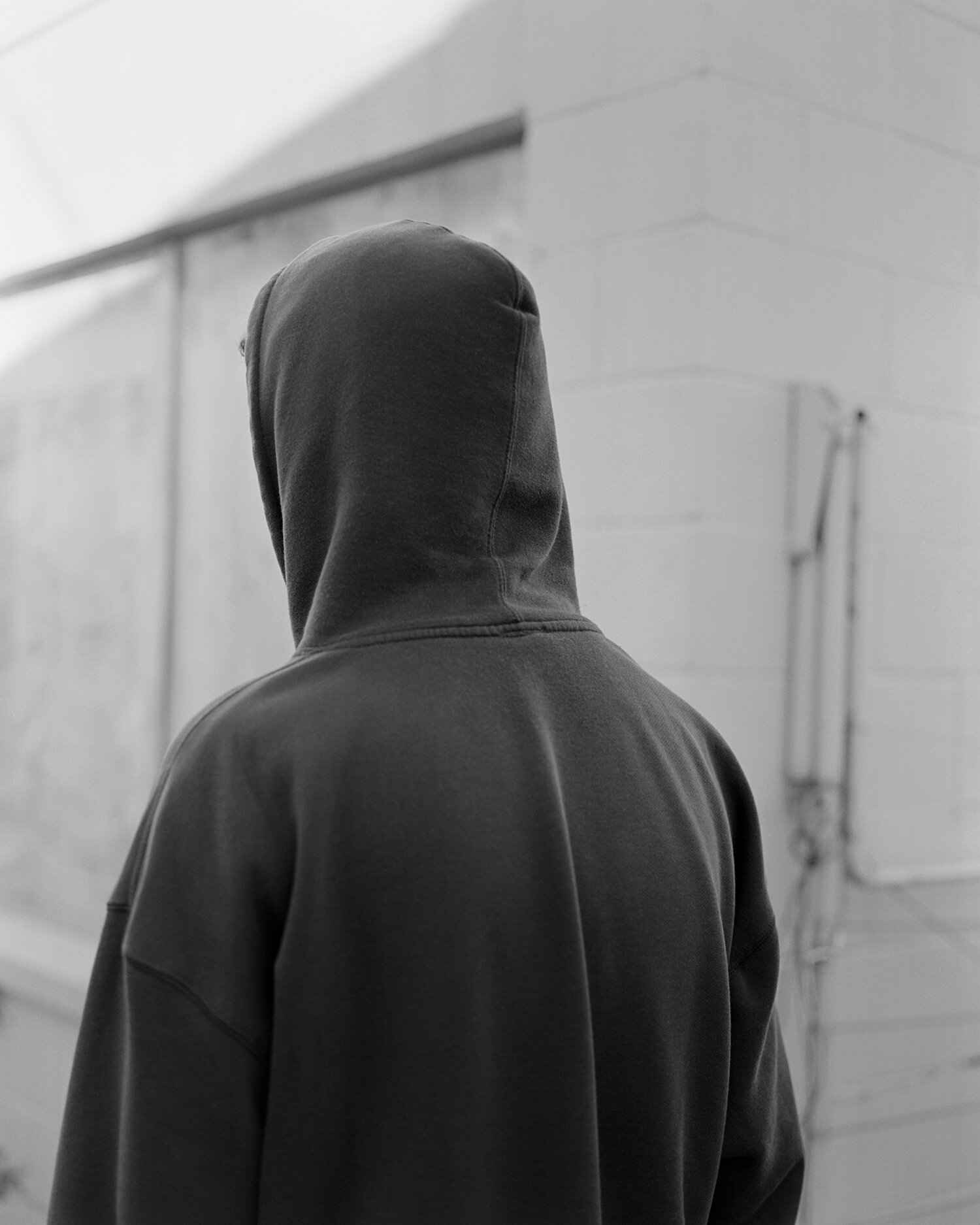

In the work of Harry Culy and Chevron Hassett we see a care in collaborating with those portrayed. Hassett breaks the documentary one-way authorship model entirely by placing next to his portraits of year-13 Taita College students posters made by them. In Culy’s Mirror City the mirror appears to be moving its angle all the time, so that instead of reflecting ourselves, it reflects what others might see, and how the young might tentatively assert themselves in public space. Rather than left safely, removed in a place as voyeur, our screen is shattered (in one image literally) or a new personal screen is placed before us - the protective screen of a mobile phone stuck to glass, itself photographed through glass. A hall of mirrors.

(Harry Culy, Mirror City)

Mirror City is as Culy says both an expression of his own place in the city and that of those he portrays. Working with a large format 4 by 5 camera (much like another great chronicler of hidden shared Wellington spaces Andrew Ross), Culy evidently isn't snapping quickly but working with his subjects to set up an image in shared space. Do we relate the tag ‘Best Friends Forever’ to one of the portraits of young women presented either side of it, or ‘Davo’ carved in a tree? We get to create the stories. Like Hassett the works assert the creative acts of others, but disrupt our sense they have been made for us.

Safe distance is also removed in David Cook’s Social Housing, and again the collaboration between photographer and subject is clear. These are, as he says, neighbours and friends. He lives next door. Yet there is still distance, space we the viewer might occupy. Cook’s portraits are in contrast for example with British photographer Richard Billington’s well-known 1996 series Ray’s a Laugh (which some have claimed redefined at the time the documentary narrative). Here images of Billington’s parents and their pets in their tower block apartment are marked for the viewer by a true but uncomfortable voyeurism for us of a family caught in an alcoholic haze (a series that got dubbed ’squalid realism’) (1). As the title suggests, we laugh at them rather than with them.

(David Cook, Social Housing: 1, John at Newtown Park; 2, Newtown Park Apartments I; 3, Paul; 4, Paul at home; 5, Newtown Park Apartments II; 6, John; 7, Newtown Park Apartments III; 8, Shelley and Karl; 9 Shelley; 10 Newtown Park Apartments IV; 11, Danny; 12, Katherine and Terry; 13, Newtown Park Apartments V; 14, Alex; 15, Raymond; 16, Seventh floor; 17, Michael; 18, Granville; 19, Mike).

In contrast in Cook’s image Karl and Shelley a couple in a lift embody love and care for each other. The elevator is itself a liminal space in which they close their eyes and dream, just as another resident Paul does in the images that follow. None of these figures face us - we don’t interrupt their thoughts - yet through Cook they welcome us to join them in their dream space.

In Cook’s portraits there’s a clear sense subject and photographer are sharing something with us together, but open to us making our own sense. As John leans over a fence, secateurs in hand, he’s framing our view through his own cuttings, his own creative dreaming, as Cook is also doing. John’s not looking for an escape - no snipping through the rusted chainlink fence - he’s mentally already escaped. Rather he’s leaving us a place to creep through as well.

The refuge landscape of Cook’s Social Housing is interesting for not being nearby Newtown Park or the Town Belt, but the closer scraps of common space within and abutting the towers. I dare say it reflects its occupants’ lives.

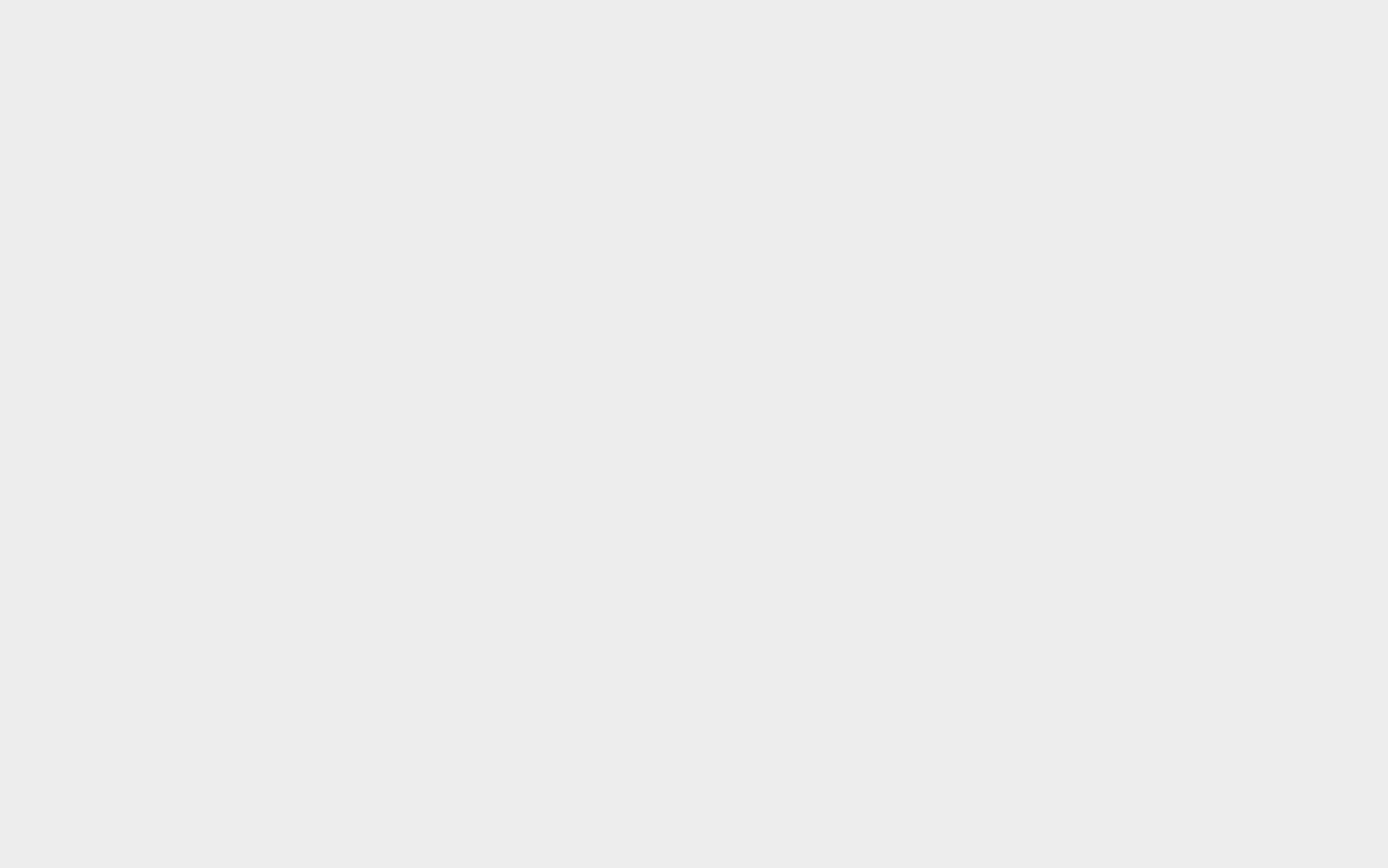

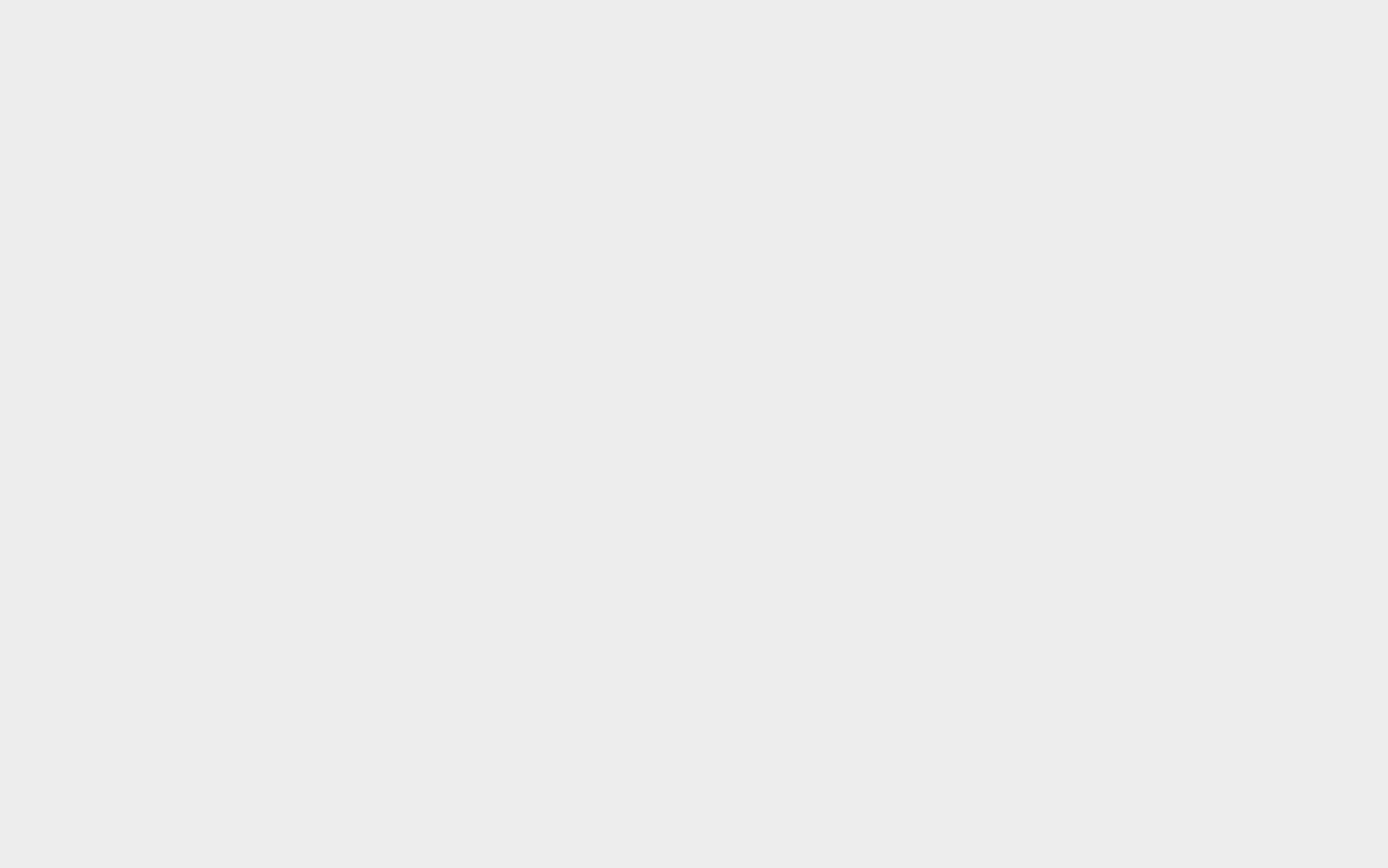

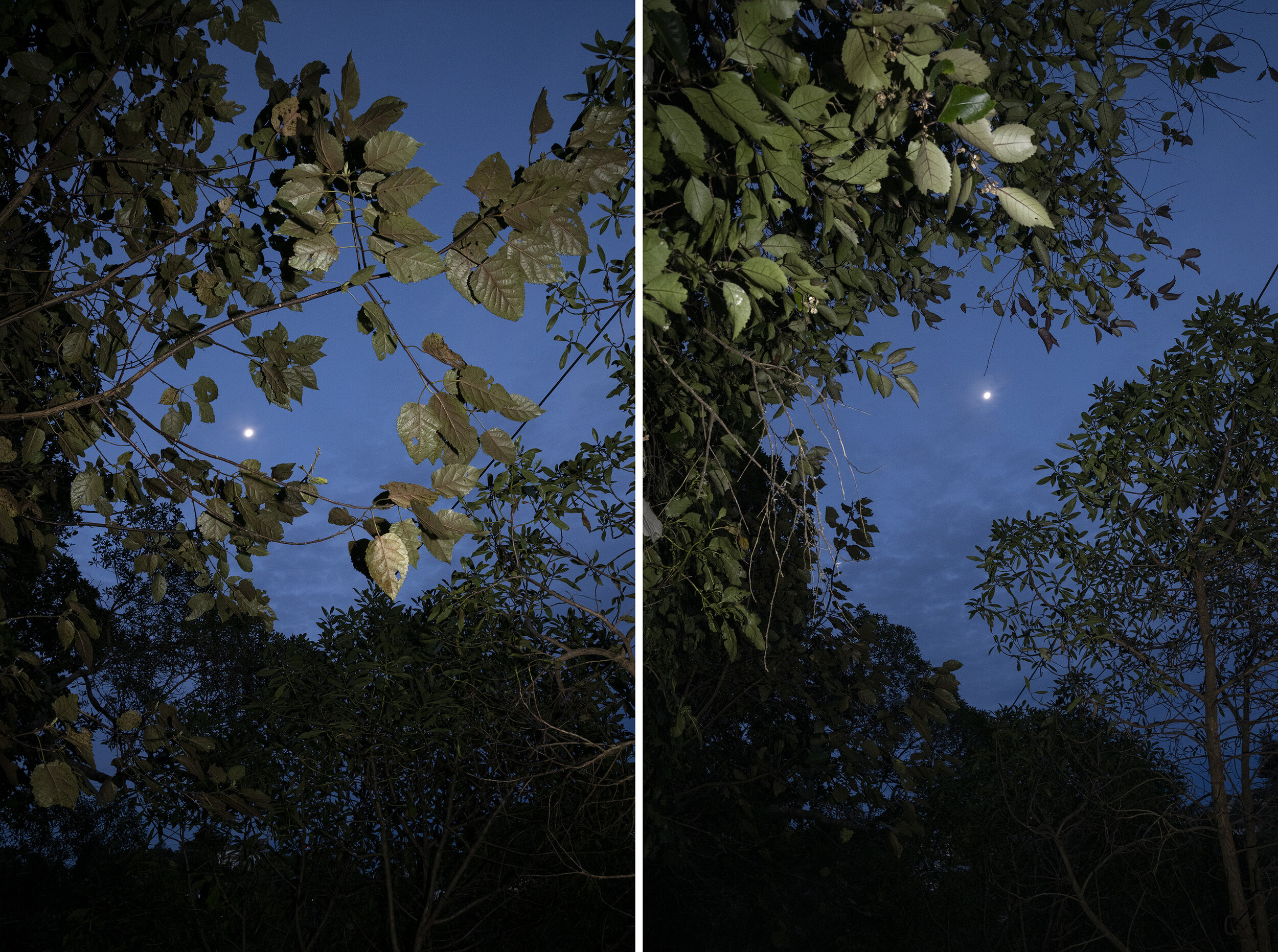

(Jane Wilcox, Māhina)

In Jane Wilcox’s Māhina I am taken back to that place of the marizpan tree, a landscape of prospect and refuge. A place I now mould to my own imagination. The images are shot at twilight, that in-between time where the physical world at our feet meets the creative world of our head. It is worth thinking of the science in this space of magic: twilight, or the gloaming, is a time when the sun has gone below the horizon but its presence is still felt. Our experience is dramatically altered by this fact - shadows disappear, and objects become silhouettes. Their sculptural texture changes.

In Wilcox’s work we’re not looking at the landscape, we’re within it, looking up and out to the tree-framed sky. This is a liberating creative space for the viewer, familiar from childhood. A leaf-lined cubby, protected yet gazing out. Wilcox’s images are distinctive for her unabashed use of a flash. What usually denotes the marketed fiction of fashion and fairy tale here sees light bounce off the underside of leaves, emphasising how the world of make-believe operates around us, with the darkness beyond. Emphasised is the coexistence of internal and external worlds, just as in Hassett, Cook or Culy’s series the viewpoints of photographer and subject coexist. Wilcox’s blooms and fronds are beautiful in a sublime Romantic tradition - I’m reminded in the reaching forms and palette of the baroque ( as if we are looking up at a great painted ceiling) - but there’s no story I’m being told. I am left to play.

(Mary Macpherson, Of the Hill)

Meanwhile, google Ahumairangi and the most common perspective of this Wellington landmark is the hill itself but of one particular view - the dress circle of buildings around the inner harbour, from the wharves to Roseneath, with the Orongorongos in the background. This is the ‘money shot’, a projected shared vision of economic prosperity wrapped up in a graceful scenic curve. In her Of the Hill series on Ahumairangi Mary Macpherson counters this. The gorse hills behind are favoured, views are interrupted by power lines, or the grass of the hill rises up close in the foreground dominating the harbour. So close Macpherson could be rolling down it.

These photographs are mainly of the hill itself, even if that might at first seem to be a road or a parked car. A broken railing or a pile of fill are punctum, stop signs for the viewer, welcoming us to play in these neglected spaces rather than gaze off into the distance. Macpherson takes up the challenge of recognising that the most extremely banal of spaces right in front of our homes are places we escape into. Even an empty concrete walkway invites play.

Macpherson’s images test pictorial landscape stereotypes. One image sees us looking down at homes peppering the hill, taken amongst the ground level wild grasses and blackberries (obscuring the view as much as the powerlines. This view picks out those neglected hillside green patches that have been left to creeping weeds as much as the pretty wooden homes, and in particular those around an odd oblong shaped walled and decked extension of a home’s private property, the wall marking out the strangeness of fee simple title boundaries. Meanwhile amongst the images of park land a series of giant tree stumps, mark how this town belt is changing. Most photographers would tilt the camera to be level with the ground, but instead Macpherson is one with the hill, recognising its gradient. I think of playing on those stumps, but moreover the big old pine trees in Okura we made huts in. The huts where I had my first real hot kiss and fed a possum milk in a saucer - creating our first precarious homes, like birds in their nests.

(Peter Black, from Blacksville)

If Macpherson sets a scene for us to enter, Peter Black’s Blackville provides a play full of characters for us to dance with. It’s a reminder too that the liminal spaces can be our central city streets. When I say ‘play’ there is both theatre here, with the artist and viewer as directors, but also a rare welcome abundance of smart witty imaginative play by the photographer, which is encouraged in us.

Blacksville is a parade of poignant object theatre with, again, the narrative left for the viewer to write. The actions of people and the gestures of the world around us - a branch offering fingers, the eyes of a sinister doll - are equally animatronic. One thing leads to an association with another. A red dress hangs lit in a shop window across an Auckland intersection at night. It looks possessed, and indeed in the next image its energy has morphed into the clothing of a figure deep in their own world seen through a laundromat window. There are many of these magical narrative switches encouraging the viewer to start conducting some telekinesis of their own.

Red dances deliciously through the series, from a dress to a coat to a pair of red shoes, asking to be worn and danced in. It could even be a homage to the colour’s use in Nicholas Roeg’s 1973 classic film thriller Don’t Look Now. Generally this series feels influenced by such cinematographic tension and meaning-building plays. In another image a girl quietly plays with the sugar sachets in a tearoom. The red chairs around her look like they may have a life of their own - or is it she who is able to move them with her mind? Black’s scenes are hilariously haunted. We see the world around us as alive with activity which is as much the making of our own minds as it is of the world itself

Another Black image brings me back to Chevron Hassett and Harry Culy. It is of a young couple outside a hall I recognise in Wellington’s Cambridge Terrace. They are utterly comfortable in their own space - a place I’d venture older couples would find awkwardly public as a place of passage. Is this a portrait? They certainly aren’t puppets. At ease with the city as their landscape perhaps they are the puppetmasters.

(Chevron Hassett, One Heart, One Beat)

Young people and their landscape of belonging - their tūrangawaewae - has long been a concern of Hassett’s, both for himself and his communities. He’s been exploring how portraiture might reflect identity as one embodied in the landscape in which we stand. In the Hutt Valley, as we see in ‘One Heart, One Beat he finds a way to give often silenced subjects their voices back. To feel seen.

Countering negative stereotypes, on the eve of stepping out of uniform these final year students of Taita College look ahead with both positivity and quiet strength. ‘It is your world’, reads a poster, and indeed this is Hassett’s old school, the project a chance for him to reengage and see what has changed and how he can contribute.

Hassett’s approach is disarmingly simple and bold but this fits with the charge of his wider social purpose. Year 13 is a tricky in-between time for young adults.. As part of a Creative in Schools project Hassett focuses on empowering these rangatahi’s potential and purpose - he turns down his own ego entirely and thinks of his community. As he comments, the standard approach would have been a mural, but he’s been careful to use different media to give these students individual agency in the world as they transition, rather than just fade into the painted backdrop. Still, the artworks created here form part of a giant collage work which was installed at the college.

Culy, explores similar ground but with an entirely different aesthetic. Two young people sullenly stare and stand their ground. It might not radiate positivity but there’s still a sense of looking forward. The neglected weed-ridden pockets of land behind the backs of fences, the parking lots behind buildings, the bus shelters and the gutters - these are their own landscape to grow bigger in.

Mark Amery is an editor, curator, critic, broadcaster and journalist, interested in the role of the arts in public media and public space. Codirector of public art organisation Letting Space, Mark has worked across radio and print media since the early 1990s, contextualising arts practices within social, political and environmental spheres. He is a contributing arts editor and critic for the Dominion Post, and a producer and presenter for Radio New Zealand. With others he has established a radio station and web platform for his village of Paekākāriki. He has worked with Artspace Auckland and City Gallery Wellington, and works as an advisor and curator with independent art projects.

Footnote

(1) The Observer, Richard Billingham: ‘I just hated growing up in that tower block’ by Tim Adams. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/mar/13/richard-billingham-tower-block-white-dee-rays-a-laugh-liz

Artist’s Books

Of the Hill, Mary Macpherson

Between Dog and Wolf, Jane Wilcox

Jellicoe & Bledisloe, David Cook

Motel Life, Peter Black

We need your help to continue providing a year-round programme of online reviews, interviews, portfolios, videos and listings that is free for everyone to access. We’d also like to dream bigger with the services we offer to photographers and the visual arts.

We’ve partnered with Press Patron to give readers the opportunity to support PhotoForum Online. Every donation helps!