NEW ZEALAND’S PHOTO TREASURES HEADING FOR THE TIP? - Part 6

Notes on the collection of photographers’ collections for posterity

A PhotoForum discussion paper by John B Turner

Part 6: Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira & Auckland Libraries Ngā Whare Mātauranga o Tāmaki Makaurau

“Sadly, Fifi Wynn-Williams dug a hole in the driveway at her house in Takapuna, dumped her glass plates in it and then laid a new concrete drive over the top just to get rid of them. Of the few remaining boxes of Wynn-Williams negatives, several were consigned to the recycle bin before I got my hands on the rest.” – Keith Giles, Principal Photographs Librarian, Auckland Central Library.

01: Introduction

02: Te Papa

03: Significance & Archives for Artists

04: Gael Newton: Parting with your art & Photographers’ Archives

05: Auckland Art Gallery & Alexander Turnbull Library

06: Auckland War Memorial Museum & Auckland Libraries

07: Internal Affairs & Heritage Departments

08: Canterbury Museum & Christchurch Art Gallery

09: Collection case studies: Tom Hutchins, Paul Gilbert, Max Oettli & Barry Myers

10: Curating, Barry Clothier Simple Image show & Clothier/Turner 1965 Artides show

Figure 6.01: Wayne Wilson-Wong: Motukorea - Browns Island, Tamaki Pa, Auckland c2010

Is this a significant historical photograph?

A work of art?

Or both?

That is what specialist picture librarians, curators, archivists, and historians are called upon to decide every day

***

Please consider the primary criteria:

Historic, Artistic or aesthetic, Scientific or research potential,

and Social or spiritual when assessing significance [i]

Auckland War Memorial Museum Tāmaki Paenga Hira

As befits New Zealand’s largest regional museum, which is second in size only to the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in Wellington, the Auckland War Memorial Museum has some collections that are larger or more significant than others nationally and internationally.

The Museum has collected photographs almost from its inception over 160 years ago and currently has more than three million images. In addition to his personal observations, Shaun Higgins, their Curator of Pictorial Collections, supplied a draft copy of their Collection Development Plan for 2020-2025 which includes photography. It demonstrates the breadth of their interests and present thinking and is extensively quoted here because it provides an opportunity for photographers to perceive aspects of the content of their work in ways they may not have thought of.

The illustrations are samples of images from collections of the kind that I think the Museum or other appropriate art and historical archives should investigate and consider collecting for posterity if they have not done so already. And in this case to illustrate a fruitful collaboration between independent New Zealand curators, the Overseas Chinese History Museum of China in Beijing, the Auckland War Memorial Museum, and numerous other public and private collections.

‘The Museum collects in order to support research, community access, learning, exhibitions and public programmes that can be delivered onsite, off-site and online.’

Among the broad stated aims and objectives of the Collection Development Plan are to:

• Build on existing collections and past collecting plans and policies, and to articulate clear priorities for collection development over the next five years.

• Create a framework for the acquisition of objects collected that will enrich the permanent collections.

• Assist with the allocation of existing and future resources (human, financial and physical) for collection development, care and interpretation.

• Help identify objects that are inconsistent with this plan and which may be refused or considered for disposal.

• Raise organisational awareness of the aspirations contained in this plan and foster acquisition proposals across all collecting areas.

Among their further objectives are to:

• Align the Museum collections with regional priorities and other collecting institutions in Aotearoa New Zealand.

• Manage collection growth so that resources (human, financial and space) are sustainably allocated to collections.

• Ensure collections are relevant to the research needs of the Museum: audiences onsite, off-site and online, iwi partners and other stakeholders, in line with He Korahi Māori, and Pacific communities, in line with Teu le Vā.

They also prioritise the task of anticipating future use of their collections and creating exhibitions among their responsibilities.

The Museum stresses its long-term purpose of being the kaitiaki (custodian) of the collections that are held in trust for Aucklanders, New Zealanders, Pacific communities and agencies, and international communities, specifically in:

• the recording and presentation of the history and environment of the Auckland Region, New Zealand, the South Pacific, and in more general terms, the rest of the world, as priorities, as are its conservation of the heritage of the Museum, and its role as a war memorial centre.

• It aims to celebrate the rich cultural diversity of the Auckland Region and its people, through education which involves and entertains people to enrich their lives and promote the well-being of society, along with the advancement and promotion of cultural and scientific scholarship and research.

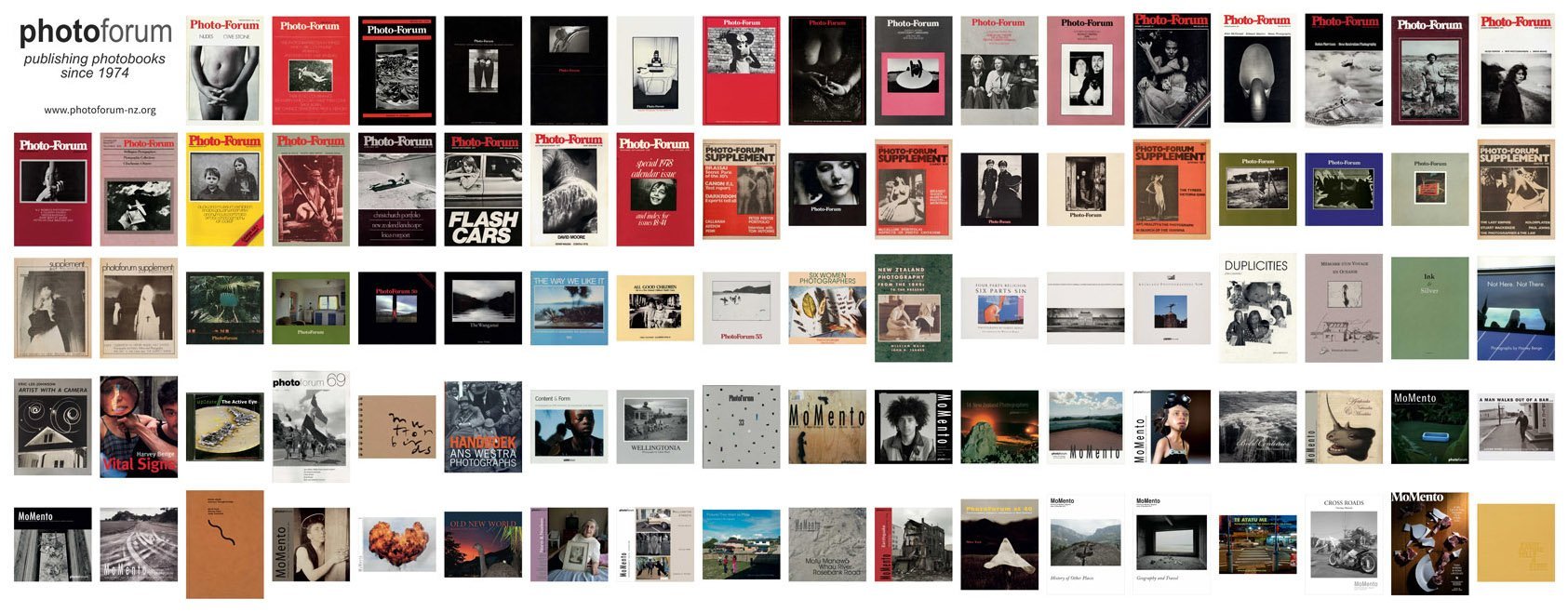

Figure 6.02: Bernie Harfleet: Photograph and text about his adoptive father from PhotoForum Momento 11: Norm and Noeleen by Bernie Harfleet and Donna Sarten, PhotoForum 2012

In relation to other collecting institutions in Aotearoa New Zealand the Museum acknowledges that our cultural heritage is preserved in a network of museums and other public collections in Auckland and beyond and works to avoid unnecessary duplication. The museum considers the collecting policies of other organisations with similar collections.

Their aspirational goals are aimed at the:

‘achievement of customer satisfaction by consultation, responsiveness, and continuous improvement; leadership through professionalism, innovation, and co-ordination of effort with relevant organisations, and greater financial self-sufficiency through the prudent operation of compatible revenue-producing and fund-raising activities which supplement public funding and provide maximum community benefit from the resources available.’

Auckland’s other ratepayer-funded collecting institutions include the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, Auckland Libraries, the Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT), and the New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui Te Ananui a Tangaroa in particular. No mention is made of any links with the University of Auckland or other tertiary institutions in Auckland which have their own collections.

I don’t know if records are kept of collections that are rejected, but the Museum acknowledges that each of these institutions has a different strategic goal for their collections, which allows for limited overlap in collecting objectives. Their intention is to work together informally to minimise collection duplication, and presumably, to help ensure that significant collections are not lost in the process (my emphasis).

The Museum notes that the Auckland Art Gallery and Auckland Libraries, for example, share several historical deposits from the same source as the Museum, such as those of Sir George Grey and James Mackelvie. The Museum Library, they note, operates an informal understanding with other documentary heritage institutions in the region, and nationally – including the Alexander Turnbull and Hocken libraries about areas of collection responsibility and focus.

Principle of collecting and disposal

Acknowledging its finite resources for its activities and care of its collections, the Museum is also aware that over time, collection priorities shift as does their use, so collection priorities and criteria are reviewed regularly, including both acquisitions and disposal options. They note that their collections are acquired variously through gift, purchase, commission, field collecting or exchange. Its preference is for ownership and copyright to be transferred to the Museum, but also continues to consider long-term loans for the safekeeping of objects such as Taonga Māori. (My emphasis).

A large portion of Auckland Museum’s maritime collection was transferred as a loan to the New Zealand Maritime Museum in 1993, so that is no longer an area of their own collecting priorities. Ideally, this suggests to me that it would make sense if the late Paul Gilbert’s diverse collection were to go to the Auckland War Memorial Museum which could then decide how to share the important maritime heritage portion of Paul’s output with the Maritime Museum which already has some of Paul’s work. But whether that will happen is another question. In my opinion both Paul Gilbert’s collection and Barry Myers’ New Zealand work are suitably unique and worthy treasures that by all criteria should belong in the AWMM’s archive, so I have included brief case histories on Gilbert’s and Myers’ collections in Part 9 of this report.

The Museum’s Collection Development Committee is comprised of the Director of Collections and Research, Head of Human History, Head of Natural Sciences, Head of Documentary Heritage, Head of Collection Care, Head of Exhibitions and Manager Māori Development, which reviews and assesses proposals for acquisition, disposal, repatriation and long-term loan of objects and oversees policies related to collection development.

Figure 6.03: Sale Jessop (1966 -2012): Octopus Island, Samoa, 1988. This photograph, which includes Fatu Feu'u, the distinguished Samoan-New Zealand artist at bottom right, was made when Sale, a third year Niuean student at the Elam School of Fine Arts visited Samoa in 1988. Charles Sale Jessop became a prominent artist and art teacher in Niue. Turner Collection

‘The Museum will only acquire items for its collections where it has reasonable resources necessary to provide for long term care and preservation of the object, such as appropriately protected and environmentally controlled storage space and conservation treatments. And as a general principle, preference is will be given to collecting items which are relatively complete and in good condition, and therefore do not require significant collection care resource to stabilise.’

The Museum’s primary criteria for assessing the significance of a collection is based on the Australian model outlined in Significance 2.0: a guide to assessing the significance of collections, by Roslyn Russell and Kylie Winkworth published by the Collections Council of Australia Ltd, in 2009 [Which is introduced in Part 3 of this Photoforum report]

To reiterate:

The four primary criteria apply when assessing significance: historic, artistic or aesthetic, scientific or research potential, and social or spiritual, plus five modifiers of the primary criteria which are provenance, rarity or representativeness, condition or completeness, and interpretive capacity.

Disposing of objects

The AWMM’s development plan helpfully discusses their approach to the thorny issue of disposing of items or a collection. Of particular interest to photographers among their weighty criteria for disposal include objects that:

• are in poor condition that have deteriorated beyond practical conservation

• lack physical or historical integrity due to substantial changes to its original composition

• are to be transferred to their country of origin to comply with international agreements

• are desired to be returned to their community of origin by descendant communities

• are duplicates, for which duplication serves no useful research or interpretation purpose

• the Museum cannot adequately care for or store

• have no potential use for research, community engagement, display or interpretation

• have legal title vested in a party other than the Museum

• have unknown provenance

• are known to be a fakes, forgeries or copies and are not suitable for exhibition, research or interpretation

• have been unintentionally lost, destroyed or stolen and their recovery is deemed unlikely

Assessing Potential Acquisitions

The Collection Development Committee assesses potential acquisitions using the following criteria:

• Significance and relevance of the proposed acquisition to the Museum’s existing collections and collecting areas

• The relevance to the natural and cultural heritage of the Auckland region, to New Zealand and the regional Pacific, and, more generally, to the rest of the world

• Research value

• Relevance to exhibition, public programme, and learning and engagement activities

• Historical or cultural importance to Auckland, New Zealand or internationally, by themselves or by association

• Rarity – item is not currently represented in the collection and, if not preserved in a public collection, may no longer be available for future reference

• Clear legal title

Collection development priorities

The AWMM defines its four major collecting areas as:

• Human History – Archaeology, applied arts and design, History (social and war) Pacific, Taonga Māori, world collection

• Natural Sciences – botany, entomology, geology, land vertebrates, marine fauna, palaeontology

• Documentary Heritage – manuscripts and archives, maps, pictorial [including photography], ephemera, books, publications, serials and newspapers, sound and moving image

• Online Cenotaph – an online repository for the official and personal stories of New Zealanders’ service in international conflict

More extensive and detailed information for each collecting area is contained in the full Collection Development Plan. In addition to the CDP, annual collecting plans provide short-term priorities which are completed by the curators for their respective collection area and submitted to the Collection Development Committee for approval.

Although the emphasis here is on the collection of photographs, which the Auckland War Memorial Museum categorise under their Pictorial umbrella, it may be helpful for photographers to think not only of their photographic output but also that perhaps their own life experiences may be of relevance within the social history of New Zealand, in the way our pioneer amateur and professional photographers are starting to be recognised.

History collection

The Museum’s History collection had two main components that were broadly termed “Ethnology” when it was founded. Since then it has separating into Applied Arts & Design, Archaeology, History (Social and War), Pacific, Taonga Māori and the World collection.

Photographers may not own the actual objects they have photographed, but being representations and records of objects, their photographs might be of interest to a Museum and the following descriptions might help the process of sorting and culling one’s work?

In my own case, for instance, I deliberately set out to photograph my parents and the interior of the rented state house in Lower Hutt in the 1960s as typical of many working-class suburban homes with a kitchen safe instead of a refrigerator, a copy of Gainsborough’s Blue Boy as a nod to art and a tiny library of sports and cowboy books. The blinds of our family living room were nearly always pulled so the light did not fade the hard-won carpet or radiogram treasured by my Depression-era parents. I have included some of those images in this report as a reminder to other photographers who will have records of the interiors of their family homes and workplaces, etc., that illustrate how household items are valued and used.

Applied Arts & Design

The AWMM’s Applied Arts & Design collection was established in 1966 by Trevor Bayliss.

It covers furniture; ceramics; glass; metal work; costumes; textiles; jewellery and accessories; mixed media/new media; musical instruments; horology; and objects d’art.

Over the next five years we will strengthen our holding of key 21st, and mid-to-late 20th century designers and makers and will collect objects which will support key stories identified through gallery renewal projects.

Archaeology

The Archaeology collection was established in 1966, when an Archaeologist’s position was funded by the E. Earle Vaile bequest to Auckland Museum.

This is the only archaeological position within a museum in New Zealand and, significantly, Auckland Museum is the only institution to curate archaeological assemblages containing not only formal artefacts but faunal bone and shell samples, stone flakes and botanical material from excavated sites in the Greater Auckland, Northland and Coromandel Peninsula regions. There are several internationally significant collections within Archaeology, including Oruarangi on the Hauraki Plains and Houhora in the Far North. The Museum also holds objects from Chatham Islands and Rangitāhua Kermadec Islands; Pacific collections, such as those from Samoa (held on behalf of the Samoan Government) and a large and internationally significant collection of approx. 20,000 stone artefacts from Pitcairn Island.

The Museum aims to collect assemblages of different ethnic groups such as Chinese in Auckland and to enhance collections from early 1820-1850 European settlement in the Greater Auckland area; and to purchase significant items in order to fill the gaps in the world collections. We will also work with iwi owners to encourage them to place significant items or excavated assemblages of taonga in the Museum under a loan agreement.

The History collection was established in 1992, by the amalgamation of the War collections (established 1920) and the Colonial History collection (established 1965) together with the Numismatic, Maritime History and Philately collections, and with the appointment of a dedicated social history curator. The collection has two main strands: New Zealand at War, and Auckland-New Zealand social history; and although they are treated separately, it acknowledges that there is some overlap between the two themes though they are treated separately.

Figure 6.04: Ian Macdonald: Curlew Island 1990. A leading conservationist, photographer and gallerist, Macdonald’s work was shown at the 2014 Pingyao International Festival of Photography, 2014, along with that of Martin Hill and Craig Potton in ‘To save a forest…’ Courtesy of the photographer

Figure 6.05: Ian Macdonald. An image from his work as a stills photographer for the BBC series Walking with Dinosaurs. Screenshot. Courtesy of the photographer

Figure 6.06: Ian Macdonald: A scene photographed for the BBC series Walking with Dinosaurs, with the digital dinosaur include. Screenshot. Courtesy of the photographer

It is highly likely that a photographer’s life work could be relevant to more than one of the Museum’s collection interests. For this reason, I include their full description of their acquisition objectives for their Social History collection below:

Social History Collection

Over the last 25 years, acquisition objectives have focused on expanding the history collection to include 20th century objects, the stories of women and children, the processes of migration and settlement, the everyday lives of Aucklanders and local community organisations and businesses. In line with the strategic direction of the Museum, the social history collection seeks to represent the needs of Auckland’s communities by documenting the histories and experiences of all Aucklanders, past and present. In order to achieve this, social history collecting priorities are continuing to move away from ‘first’, ‘important’ and ‘unique’ objects, towards collections that reflect the stories and experiences not currently represented in the collection. This requires shifting away from passive collecting (i.e. collecting in response to offers from the public), and prioritising actively identifying and targeting collections that enrich understanding of histories not currently reflected in our collections. Identified gaps that will be prioritised include objects representing significant past and contemporary issues and events in Auckland, and objects representing contested histories or histories of under-represented communities in Auckland. The gallery renewal project over the last three years has provided an opportunity to begin focusing on these areas of collecting. Historical context is particularly important for the history collections, so priority will also be given to objects with a strong provenance and social or cultural context.

War History collection

The War History collection was established in 1920 following the end of World War One and the AWMM is the only New Zealand museum that includes war history as a major theme. The collection scope relates to New Zealand involvement in warfare but has an Auckland focus, and approaches this topic from a social history stance, with the focus on the wartime experiences of individuals, military, and civilians.

Currently, the collection addresses four major themes: the experiences of war, the impact of war, remembering war, and the materiality of war.

Acquisition priorities include: objects associated with particular campaigns, regiments, and events, the role of women in wartimes, and information on the lives of conscientious objectors. At present their Online Cenotaph only includes records for imprisoned conscientious objectors during 1916-1920.

Pacific Collection

The Pacific collection is the most diverse and significant collection of its type in the country and covers ‘all the cultures of the Pacific, from West Papua, north east to Hawaii, to south east to Rapa Nui Easter Island and includes material from Auckland-based Pacific communities.’ The collection is not only geographically diverse but ranks as a major world-class collection. Along with the Taonga Māori collection it has an international reputation.

The Pacific collection aims to represent and preserve a well-balanced range of arts and material culture from tropical Polynesia, Melanesia and Micronesia. For Pacific island-based groups and New Zealand-based Pacific communities the focus expands to include aspects of contemporary art, specifically those fields of contemporary Pacific art that derive from, relate to, resonate with, or bear reference to the traditional arts of these groups, or enhances existing collection strengths. Among their other identified collecting priorities, which photographers could likely contribute are: Post-war migrant histories and accompanying material; Material brought by migrants when moving to settle in Auckland; Protest movement materials, historical and contemporary; Pacific peoples engaged in climate change protests; reflections on contemporary Pacific peoples in Economic Development: Business, Science, Design and Innovation sectors; Auckland based NGOs and other organisations funded to work in Pacific related projects or with Pacific communities in Auckland and the Pacific region.

Taonga Māori

Although the objectives of the AWMM Act 1996 focuses on the recording and presentation of the history of the Auckland region and its people, many of its the early Māori acquisitions came from across New Zealand and consequently has a wide tribal representation of the arts and material culture from New Zealand Māori and Moriori.

During the 2000s the focus expanded to include selected aspects of contemporary art, specifically those fields of contemporary Māori art that derive from, relate to, resonate with, or bear reference to the traditional arts. Collecting in this area has been a priority in recent years and will continue to be more vigorously pursued. Museum commissioning of specific works from selected contemporary artists has occurred in the past and will increase in the future, particularly as part of gallery redevelopment.

With the current gallery redevelopment work weaknesses within the existing collection became apparent. This has highlighted the need for a broadening of the current collection development brief to provide a finer demarcation, and greater clarity within and between, what can be loosely classed as Māori ‘art’ and Māori ‘social history’. We will increase our collection of contemporary Māori Art (c.1960s to present day) across a range of genres and mediums ‘that continue to derive from, relate to, resonate with, or bear reference to the traditional arts’ and composition of the existing collections (e.g. weaving, carving, ceramics, and sculpture)’.

Of particular interest to photographers is that:

A further broad theme of Māori social history will be established that mirrors the current Pakeha/European Social History approach where priority is given to objects of everyday life supported by historical context. This latter theme seeks to show Māori participation in NZ life throughout the nineteenth century and up to the present day across all areas including domestic, political, social, economic and international arenas (e.g., kapa haka costume, folk art carving, material associated with early 20th century figures such as Māori politicians, religious figures, Māori organisations such as Māori Women’s Welfare League, Māori participation in sport, etc.). This can include material that has not necessarily been made by Māori but relates to Māori history, art, culture, and traditions and or was used by Māori. Collecting in these areas will be undertaken in conjunction with curatorial colleagues from History, Applied Arts and Design and Documentary Heritage.

World Collection

The World Collection consisting of approximately 9,000 objects, is diverse, the largest and most significant collection of its type in the country. The continued development of this collection is important to enable the presentation and representation of a well-balanced range of arts and artefacts of non-Western, non-Pacific and non-Māori cultures. With increasing numbers of migrant groups to New Zealand – and specifically to Auckland – it is important that Auckland Museum can reflect the changing cultural landscape and the creativity in the interstices these new communities are impacting and creating from within New Zealand society.

Collection Development Priorities include: ‘material brought to NZ by migrants as expressions of identity, status, importance; documentation of historical occurrences within migrant communities; reflections on contemporary migrant peoples in Economic Development, Business, Science, Design and Innovation; mementoes of significant historical moments within the different communities; material of events that reflect a range of perspectives on event(s); objects/works associated with decolonisation – literature, artworks, applied arts, t-shirts, diaspora records’.

The Museum does not mention it as such, but it occurs to me that they might consider New Zealand photographer’s images made in foreign countries, which tend to be excluded by other institutions, for their World collection?

Natural Sciences collections

The Natural Sciences collections are primarily to support research on the biodiversity and geology of the Auckland region, New Zealand and the regional Pacific. It aims to hold a comprehensive representation in time and space of the biodiversity and geodiversity of the region. Without going into the details of the Museum’s extensive natural science collections which might include some aspects of a photographer’s content, they include the disciplines of Botany, Entomology, Land Vertebrates, Marine Life and Palaeontology.

Geology

The AWMM’s Geology collection was established in 1852 and in addition to New Zealand material, the collection has global reach, including specimens from Europe, North and South America, and Australia. Collection development priorities are focussed on opportunistic collecting, when specimens are offered to the Museum that complement our existing collections and collecting New Zealand material with research and historical value.

With the natural environment being such a popular subject for photographers it would appear likely that even a quick search of a personal collection would come up with images that would likely be of interest for geological research.

The Museum Library’s Documentary Heritage collection

The Museum Library was established in 1867 as part of the Auckland Institute, and from the 1990s, active collection development turned it more distinctly into the major documentary heritage resource for the Auckland region, with an increasing use by the general public. The Library’s collection, now referred to as the Documentary Heritage collection houses its extensive photographic holdings, described in full below. The Museum Library is an ‘approved repository’ under the Public Records Act 2005, and although they don’t appear to say so, perhaps they, unlike the current National Library management, would be interested in preserving collections of books on the international photography publications that have informed and influences New Zealand photographers in so many areas?

The nationally and internationally significant collection spans manuscripts, Museum archives, maps and plans, ephemera, serials, newspapers, books and other publications, together with extensive pictorial collections including photographs, paintings, drawings and prints. Both physical and born-digital [my emphasis] formats are collected. Areas of strength are early Māori imprints and manuscripts and Pacific missionary and pre-independence materials, human and natural history of the greater Auckland region, New Zealanders’ involvement in international conflicts and exploration and discovery.

The mid to late 20th and early 21st century wave of migration and settlement in Auckland of Pacific island groups is emerging as a significant gap. Further with some of these early migrants passing it is crucial that considered approaches and active collecting (published and unpublished etc) be undertaken. Of importance are: Climate Change in the Pacific; Cultural and social disruption, protest, impact on wellbeing and identity; Religion; Sport; Language revitalisation; Cultural revitalisation e.g. Waka ama, reo and Polyfest; Food security. In tandem with the Pacific curators in Human History the Documentary Heritage team aspire to co-collect in the areas above with a collaborative community approach.

Manuscripts / Ephemera / Oral History

In 2016 the first Curator Manuscripts position was established and with this the three collections which now sit beneath the Manuscripts umbrella (manuscripts, ephemera and oral histories) were brought together to provide a greater alignment of strategic collection priorities and growth. These collections preserve material that is significant to the social, cultural, environmental and economic history of Tāmaki Makaurau, as well as fulfilling the Museum’s function as a war memorial by holding material that reflects diverse experiences of New Zealanders in times of war and conflict.

Collecting priorities across these three collections are shifting. Past priorities have resulted in important collections that reflect particular people, times and events which, although rich and significant, do not adequately reflect a diversity of experiences and histories. To ensure the continued relevance of our collections as we move into the future, we must not only ensure that our collections are grown with consideration but that we are actively developing relationships with communities, groups and people whose histories are not currently reflected within these collections.…. While a balance must always be struck between new collection growth and building on existing strengths, this strategic direction will necessitate an active shift away from past priorities to focus time and resources on new areas of development.

Another necessary shift will be in an increased consideration for born-digital material, particularly across the Manuscripts and Ephemera collections which are now largely created in digital formats. In terms of collection development, the abundance of material created in the digital world means that our collecting approach must be targeted and focused. Rather than wait for this material to come to us, we must actively seek it by developing pilot projects in collaboration with potential sources, makers and creators of digital content and material. Collecting this material is a growing priority and will be essential to enable the Museum to tell the stories of Auckland in the future. (My emphasis. One hopes also that they recognise the need to collect photographer’s analogue collections before it is too late.)

There is an obvious cross over here with the subject matter of photographers who have documented their own lives and aspects of the communities familiar to them, as an alternative to the official nation-building narratives of governmental and business propaganda toward the image of clean green, classless, racially harmonious and peaceful society.

The Museum seeks to increase its collecting on:

• Migration and settlement, particularly of non-British communities and 20th century migration

• Empire and colonisation - with emphasis on the NZ Wars

• Material that reflects research and discovery around biodiversity and human impact on the natural world particularly regarding climate change and sustainability

• A focus on more diverse representation of war and conflict including women, Māori, Pasifika and counter voices such as pacifist and protest

• Contemporary Auckland – social groups, community perspectives

• Collections relating to Māori – urban migration, mana whenua perspectives, Te Reo Maori,

• Collections relating to Pasifika communities in Auckland, post-war migrant histories and contemporary culture.

• History of childhood

• Collections that reflect gender and sexual identity

• Holistic and collaborative collecting across collection areas

• Personal papers relating to significant Aucklanders – with a focus on women

Ephemera

Ephemera is typically unpublished material that contains descriptive and/or illustrative content that relates to an event or is intended to convey a message to a broad audience. These items include posters, pamphlets, cards, menus, tickets, stamps, programmes, advertisements and promotional material in both analogue and digital form. Although these items are usually intended for temporary use, they are a rich resource that provide a snapshot of social conditions, design, propaganda, advertising and popular culture.

Major themes of the ephemera collection (in approximate order of collecting priority):

• Tāmaki Makaurau and the history of Auckland Province

• Protest

• War and conflict

• Significant Auckland organisations

Oral History

Oral history is a relatively new area of focus for the Museum in the 21st Century and it is now actively collecting and commissioning oral histories. The Museum’s existing holdings primarily reflect its function as a war memorial and include interviews with Holocaust survivors and veteran testimonials. Oral histories present a unique opportunity to allow individuals and communities to speak about their experiences in their own voices.

The development of Auckland Museum’s oral history programme is built on capturing stories that reflect the diverse cultural identity of Tāmaki Makaurau with a firm focus on supporting gallery renewal, Future Museum and adding to the knowledge of existing and new acquisitions. Teu le Vā provides the framework to develop an oral history collection that reflects Pacific community voices in Auckland.

Figure 6.07: Barry Myers: Lion Breweries bartender, Newmarket, c. June 1981. He tended the bar for production staff and blue-collar workers, which was frequently open during the day. The beer was free, I think. and in addition, each employee was given a free case of beer each month. There was a separate bar and dining area for white-collar employees. I also photographed at Lion’s headquarters in 2012-13 when the brewery itself had moved out of the area. – Barry Myers

Myers, a US photographer, worked on his Newmarket project in 1981-82 and again in 2012-13 spending over two years documenting what was once called New Zealand’s Smallest Borough.

Figure 6.08: Barry Myers: An accountant working at Lion Breweries which was the largest employer in Newmarket, June 1, 1981. I also photographed at Lion’s headquarters in 2012-13, when the brewery itself had moved out of the area. – Barry Myers

Pictorial collections and Photography

Pictorial is comprised of Photography, Artwork (such as Paintings, Drawings, Prints, Bookplates) and Moving Image collections. The Museum has been involved in collecting photography and artwork almost from its inception. There are now more than 3 million photographic images, some 3000 artworks ranging from oil paintings to original bookplates and almost 400 moving image reels. Focus is now firmly on original acquisitions although some copies exist within the collection.

Major themes in the Pictorial collection

1. Tāmaki Makaurau and the history of the Auckland Province (physical growth, social and economic development).

2. Social awareness (civil rights, protest).

3. Indigenous culture and Aotearoa (especially within the context of Tāmaki Makaurau).

4. Cultural identity, particularly in a Tāmaki context (referenced in Future Museum, Māori, Pacific, Asian, European and many others).

5. Conflict, especially New Zealand involvement (including peacekeeping and anti-conflict/response to conflict).

6. History of photography (Auckland photographers, New Zealand photographers and a high impact international context)

7. Land and water, particularly in a Tāmaki context (changing land use, urban development, volcanic cones, environment).

8. Architecture, Townscape & Streetscape (Auckland city and N.Z. small town streets, buildings etc).

9. Scientific exploration (including expeditions such as, Antarctic, Himalayan, Kermadecs).

10. Natural History (botanical, ornithological, marine).

Photography

’Over the next five years there is an opportunity to develop a stronger connection to makers and photographic practice. Whilst subjects (photographs of) continue to be of interest, a photography collection should also reflect the person behind the camera and the practice of taking pictures. A soldier snapshot (of which we have many examples) is not the same as photojournalism in conflict (of which we have few examples).

Focusing on areas of specialisation enables capacity to expand particular areas relevant to photography as a practice, such as photojournalism in response to conflict or portrait photography as identity. Some will overlap such as commercial, fashion and food. Collecting portrait and snapshot photography enables the collection of selfies as a photographic phenomenon. Priorities in these areas will inform collecting alongside the general thematic interests associated with Pictorial’.

Figure 6.09: Barry Myers: Tania Da Silva and Giselle Chaves both work on the hair of their client at the Belladonna Beauty Salon, located at 53 Davis Crescent, Newmarket. Da Silva was the owner of Belladonna, which shared space with the Preto Hair Salon, a men’s barbershop. This photograph was taken on April 16, 2013. – Barry Myers

Figure 6.10: Barry Myers: Auckland Grammar School, June 17 or 18, 1981. These boys are playing a game of dodgeball during their lunchbreak. Auckland Grammar School was known as the best public boys’ school in New Zealand at the time. I photographed there for two days in 1981 and made several visits during my 2012-13 continuation of my Newmarket Project. – Barry Myers

Figure 6.11: Barry Myers: Dilworth School, December 2, 2012. A boy struggling to put on his robe for a Christmas performance of the Dilworth Junior Campus Choir. This is part of a series showing various stages from the awkward beginning to success, from my extensive coverage of Dilworth, an independent full boarding school for boys. – Barry Myers

Figure 6.12: Barry Myers: The proud parents of a new student on his first day at the Junior Campus of the Dilworth school look over his room, February 4, 2013. (Dilworth is technically in Remuera, bordering on Newmarket, and the head of the Junior School was Peter Vos. – Barry Myers

Figure 6.13: Barry Myers: Ranfurly House, Newmarket December 19, 2012. Residents and clients of Ranfurly House participate in a Christmas Nativity play. Ranfurly House, located at 56 Ranfurly Road had residential and day care services. Previously I had photographed there in September 1981. – Barry Myers

Figure 6.14: Barry Myers: A group of girls on the lawn during the lunchbreak at Epsom Girls’ Grammar School, Newmarket, January 31, 2013. While one part of the group focuses intently on something on one girl’s mobile, the others take selfies while others look on. I first photographed at EGGS in 1981, and this was taken on one of several visits there. – Barry Myers

‘Photography is now a largely digital discipline photography from the mid-1990s onwards will feature born digital formats which represent the discipline in the same way glass and film have before them. In addition to prints it is important to collect digital photography in all its forms, ranging from single stills to 360, 3D and other imaging formats. Many photographers use platforms such as Instagram to share their work and seldom print it. A distinction is made between born digital original work and digital surrogates of analogue material such as photographs of collection objects which are not collected’. [My emphasis – Ed. There is no indication of how they are distinguished, and whether ownership is a key factor?]

Under their heading of Books and Pamphlets, the Library of the AWMM notes that they will prioritise collecting items from groups not yet represented in the Museum, such as Indian [and presumably Chinese, Korean and other] communities, and will increase their collection of material from diverse cultural identities in Auckland including contemporary and historically marginalised perspectives e.g. women of colour, LGBTQI (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Questioning, Intersexed) etc.

I am not sure if this means that the Museum will collect information about still hidden or censored aspects of society such as sex, sex work, drug and gambling addiction, alcoholism, illegal activities, the justice system and incarceration? Topics explored by well-known overseas photographers such as Antoine d’Agata, Nobuyoshi Araki, Brassai, Morrie Camhi, Larry Clark, Nan Goldin, Danny Lyon, Mary Ellen Mark, Boris Mikhailov, Joan Sinclair and Liu Zheng which have beneficially focused on their own and other countries with educational and artistic success. And in New Zealand by photographers such as Mark Beehre, Fiona Clark, Bruce Connew, Nicky Denholm, Russ Flatt, Yuki Kihara, Anne Noble, Peter Peryer, Jono Rotman, Ann Shelton, Rebecca Swan along with those not known who have kept their work and identity secret because it is seen as deviant if not illegal subject matter.

To give some idea of what photography the Museum has collected over the past decade, Shaun Higgins noted the following:

2014. Vahry Photography archive (negatives, transparencies and prints).

2014. Victoria Ginn, The Awakening Heart – A Sojourn in Papua New Guinea (prints).

2014. Jane Ussher, Still Life: inside the huts of Scott and Shackleton (prints).

2015. Gil Hanly archive (negatives and proof sheets, some exhibition prints).

2016. King Tong Ho, Objects affection (prints).

2017. John Mercer, A walk around the park – Eden Park that is (negatives and proof sheets).

2017. John Miller, The People Said No! New Zealanders oppose the Vietnam War (prints).

2017. Emily Lear, Women’s March on Washington – Auckland (prints).

2018. Peter Black, Street-Action Aotearoa (prints).

2019. John Johnston archive (studio prints, sheet film + WW2 negatives).

2019. Gail Orgias, 2017 NZ Women’s March, Auckland (digital images).

2019. Michelle Moir, Images of Maori Women, Mataahua Wahine (prints).

2020. Becky Nunes archive (negatives, proof sheets and some prints).

2020. Gail Orgias, 2019 Ihumatao protest (digital and prints) and Climate Change March (digital).

2020. Kim Hak, Alive (prints).

Artwork (Paintings, Drawings, Prints)

’Artwork has been collected as both documentary evidence and for display. Whilst history painting and portraiture has been used as visual narrative, the botanical art collection has been one of recording. In general, there is room to collect artwork sympathetic to the pictorial themes identified above.

The primary focus of collecting artwork is to document the development of Tāmaki Makaurau through paintings and drawings as graphic records that trace the growth of the city before photography became widely available as well as presenting portraits of its inhabitants. Painters such as Goldie and Lindauer also present the medium alongside photography depicting detailed portraits of Māori and Pākehā in the context of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In addition to this local context the Museum includes cultures of the southwest Pacific as home to many Aucklanders and New Zealand’s involvement in conflict (including peace keeping and opposition to conflict).

Contemporary artwork created in response to these themes as well as representation of Tāmaki is also identified as relevant to our collecting provided it is in harmony with the collecting aspirations of the Auckland Art Gallery. Artworks of the digital era are increasingly produced in applications such as Adobe Photoshop. Digital art may largely fall into the realm of the Auckland Art Gallery, but our own collecting criteria in this area should be applied to relevant material’.

Moving Image

’The Museum as a small collection of some 400 film reels , the growth of this collection has primarily followed general areas of interest rather than film in its own right. Growth in this area is minimal with the National Library’s Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision considered the primary archive of New Zealand Film. In terms of the Museum’s interests the Collections range from early flight at the Kohimarama flying school to footage from the Farmers Trading Company collection.

Collecting in this area happens in harmony with the collecting aspirations of Ngā Taonga who already care for some of our collections in specialised film storage. The only area identified for collection development is digital 360 video and drone footage’.

Publications etc.

’The Publications Collection is comprised of books, serials, newspapers, pamphlets, maps and plans.

One of the four major heritage collections in New Zealand, it sits alongside the Alexander Turnbull Library, the Hocken Library at Otago University and the Sir George Grey Special Collections at Auckland Libraries as a significant collection of historic materials reflecting New Zealand, the Natural Sciences, Māori and Pacific culture and heritage.

The Auckland Museum collection has strengths in Discovery and Exploration, the Pacific and Natural Sciences. Both the Discovery and Exploration and Natural Science themes are the points of difference between the three Auckland heritage collections; AWMM, Auckland Libraries and Auckland University. As our understanding of these strengths continues to grow and is surfaced to researchers through our own research, enhanced access and digitisation, we will identify gaps and areas for further development.

In addition to books, the Museum also collects pamphlets and will prioritise collecting items from groups not yet represented in the Museum e.g. Indian communities, and material from diverse cultural identities in Auckland including contemporary and historically marginalised perspectives e.g. women of colour, LGBTQI etc.’

Maps & Plans

I won’t go into the details here, but once again photographers might well have such items to contribute to the Museum. The shift from analogue to riskier and unproven solely digital collecting of some material is worth noting, however. The Museum’s future collecting will prioritise non-traditional or commissioned material and maps about geographical distribution of plants, and Auckland land use, subdivision plans, and modern maps and charts of the Pacific. They note that most of their map collection is uncatalogued.

Serials & Newspapers

’Today serials are acquired primarily for the benefit of staff research, to support exhibition development, independent researchers, and to capture the changing social and cultural heritage of Tāmaki Makaurau-Auckland. Serials that are permanently retained also gain value as a record of history. The extent, and in some cases uniqueness, of the Museum Library’s holdings of historical and current journals makes their research value of national importance.

Individual issues of New Zealand newspapers have been collected by the Museum since the 19th century through donation or judicious purchase. The defining acquisition was the 1967 donation by Wilson and Horton of their historical Auckland newspapers dating from the early 1840s. Subsequently we have also acquired a large run of the Auckland Star and the New Zealand Truth. This makes our collection one of the most significant collections of Auckland titles in a New Zealand institution. A further strength of the newspaper collection is those in Te Reo Māori and in a range of Pacific languages and titles representing other ethnicities in the Auckland community as well as born digital serials’.

Museum Archives

’The collection includes organisational records from the museum’s beginnings in 1852, and the establishment of the Auckland Institute and Museum in 1868 and covers all aspects of museum activity and business - curation, field trips, exhibitions, public programmes, governance records such as board and committee minutes, legal, funding and financial records, records of building and development works, corporate and business policy, plans and reports.

While managing, preserving, and improving access to the existing analogue archive of the museum is the primary focus, current records in the museum are created and only held digitally [my emphasis], across numerous museum systems. Since 2005 the Museum has been subject to the Public Records Act 2005. The act that sets out a framework and obligations regarding the creation, maintenance, preservation and provision of access to records’.

Online Cenotaph

Online Cenotaph is a unique digital collection of national significance. The “Cenotaph Database” was established in 1996, as a biographical database relating to individual New Zealand service personnel. Content was gathered from a range of publicly available sources. Online Cenotaph now consists of more than 235,000 individual personnel records.

The Museum’s intention is to provide a page for all personnel who have served our country in international and national conflicts. This includes New Zealand born personnel serving in the New Zealand and international military services as well as non-New Zealanders serving in the New Zealand Defence Force (NZ Army, Royal NZ Air Force and Royal NZ Navy). While Auckland Museum collections prioritise material relating to the old Auckland Province, Online Cenotaph covers all New Zealand.

There are specific exceptions to the Online Cenotaph inclusion criteria. Individuals who are proven to have been a part of the following service organisations, or undertook the following service, are also accepted for inclusion into Online Cenotaph:

• Members of the New Zealand Merchant Navy (e.g. individuals who were crew on New Zealand ships undertaking wartime service), or New Zealanders who were members of any Allied Merchant Navy.

• Members of the New Zealand Women's War Service Auxiliary (Overseas Hospital Division) or the New Zealand Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (Voluntary Aids) and served with Voluntary Aid Detachments.

• New Zealanders, or individuals living in territories governed directly or indirectly by New Zealander, who undertook officially organised coast watching activities during wars in which New Zealand had official involvement. This includes employees of the New Zealand Post and Telegraph department.

• Conscientious objectors. Online Cenotaph currently only includes records for imprisoned conscientious objectors, 1916-1920.

• New Zealanders who fought in the Spanish Civil War.

Priorities for adding to the Online Cenotaph includes records of Air Force and Navy personnel and defence personnel involved in international conflicts such as the Korean War, Borneo Confrontation, Malayan Emergency and later peace keeping operations.

Among the Auckland Museum’s guiding strategies are:

1) to reach out to more people

2) transform our buildings and collections

3) stretch thinking

4) leading a digital museum revolution

5) engaging every school child

6) to grow and diversify our income

Their priority on “stretch thinking” refers to the importance of generating new knowledge and ideas, being a catalyst for debate, and engaging the next generation through these activities.

Chinese in New Zealand

A mini photo essay on the history of the Chinese in New Zealand exhibitions as shown in China and New Zealand, 2016 and 2017 respectively

Independently co-curated by NZ Chinese historian Dr Phoebe H Li and the writer (photo historian John B Turner), it proved essential to have government-level cooperation between each country (provided by the NZ Embassy in Beijing) to realise this photographic exhibition. Unable to get financial support from New Zealand we had to rely on the generosity of public museums, libraries, individual photographers, and private collectors to gather the work. Our bi-lingual book based on the Beijing exhibition was financed by grants from Chinese academic sources. And unlike the system we are accustomed to in New Zealand there was no payment to the authors nor royalties.

The Auckland (digital) version did not present any of the few rare vintage historical prints or original analogue prints by living photographers that distinguished the Beijing presentation and was appreciated for helping the audience to become more literate regarding photographic processes and history. Both the Beijing and Auckland exhibitions included video content, with the AWMM version including contemporary interviews and the cartoons of Ant Sang.

Although designed as a travelling exhibition, the staff of the Beijing Overseas Chinese History Museum, which is one of 10 or more similarly dedicated museums throughout China, failed to secure additional venues despite the interest of the Guandong museum which has previously exhibited photographs of New Zealand’s predominantly Cantonese immigrants. The Auckland War Memorial Museum’s iteration was exhibited with acclaim for the whole of 2017 and later had a limited New Zealand tour.

Recollections of a Distant Shore: A Photographic Introduction to the History of the Chinese in New Zealand (1842-2016)

Overseas Chinese History Museum of China, Beijing

20 October 2016 – 19 February 2017

Installation photographs by John B Turner: Beijing 2016 and Auckland 2016 and 2017

Figure 6.15: John McKinnon, the New Zealand Ambassador to China opening ‘Recollections from a distant shore: A photographic introduction to the history of the Chinese in New Zealand (1842-2016) at the Overseas Chinese Historical Museum, Beijing, 21 October 2016. (JBT20161021_0327)

Figure 6.16: NZ Chinese historian Dr Phoebe H Li discussing Artron’s digital exhibition prints with staff of the Overseas Chinese History Museum, Beijing, 9 October 2016. (JBT20161009_0339)

Figure 6.17: After framing the lead picture, of Appo Hocton, recognised as the first Chinese person to reside in New Zealand, is being installed at the Overseas Chinese History Museum, Beijing, 19 October 2016. (JBT©20161019_0301

Figure 6.18: Digital enlargements of portraits of Appo Hocton, recognised as the first Chinese person to reside in New Zealand, his English wife and their children as presented in ‘Recollections from a distant shore….’ Overseas Chinese History Museum, Beijing, 21 October 2016. (JBT©20161021_0369)

Figure 6.19: The director of the Overseas Chinese Historical Museum, [name?] studying Les Cleveland’s photographs during the hanging of ‘Recollections of a distant shore…’, Beijing, 20 October 2016. (JBT20161020_0253)

Figure 6.20: A variety of print types presented in ‘Recollections from a distant shore….’ at the Overseas Chinese History Museum, Beijing ,2016. From left to right: A vintage Burton Bros view of Dunedin c1883 next to a digital enlargement of it; a digital enlargement of a Burton Bros cabinet-size portrait of Choie Sew Hoy c1895; and an enlargement of a 2016 cell phone photograph by Phoebe H Li of an 1881 letter from the Cheong Shing Tong society to Choie Sew Hoy. The colour differences of “black and white” analogue prints provide vital information for dating photographs, as well as emotional cues. (JBT©20161020_0282)

Figure 6.21: John McKinnon, the New Zealand Ambassador to China discussing an image during a visit by Sam Lotu-liga, New Zealand’s Minister of Ethnic Affairs, to ‘Recollections from a distant shore: A photographic introduction to the history of the Chinese in New Zealand (1842-2016)’ at the Overseas Chinese Historical Museum, Beijing, 8 November 2016. (JBT20161108-0158)

Figures 6.22 and 6.23: John Thomson: Tsiang-Lan-Kiai (Market Street), Canton, China, c1870. Two photographs from a travel album (PH-ALB-564-p74), and The Harbour, Hong Kong, c1870 (PH-ALB-564-p63), courtesy of the Auckland War Memorial Museum. Included in New Zealand Chinese in historical images by Phoebe H Li and John B Turner, Social Sciences Academic Press (China) 2017, the book based on the 2016 exhibition at the Overseas Chinese Museum, Beijing

Figure 6.23

Figure 6.24: Tom Hutchins: Not permitted to photograph the Peking Opera when he was in Peking (Beijing) in mid-1956, Hutchins took the opportunity to photograph a visiting Peking Opera troupe in Auckland during its New Zealand tour in October 1956. This performer played the part of the celebrated Monkey King in Trouble in Heaven. (RDH5x4-8) Tom Hutchins Images / Turner collection.

Figure 6.25: Wayne Wilson-Wong: Restoration of heavily damaged family photograph from China of Wilson-Wong’s grandmother and aunt, Su Moor and & Alice, 1938

Figure 6.26: Rough copies of two pages from one of the many family photo albums compiled from Diana Wong, from which a few were included in the photographic introduction to the history of Chinese people in New Zealand exhibition and book of 2016-17. Left: Photographs by NZ born Diana Wong of relatives in China in 1960 at her mother’s village, Toon Mee in Zengcheng, Guandong Province. Right: Family photographs in New Zealand of Diana’s aunt and Mother, including her closeup image of them shopping together in Auckland about 1970 (far right) and later portraits. Courtesy of Diana Wong

Figure 6.27: Studio portrait of James Shum attached to his poll-tax certificate kept by New Zealand’s Customs Department upon his departure from NZ in 1905. Shum arrived in NZ in 1871 to try his hand at gold mining in Otago before the racially discriminatory poll-tax was imposed on Chinese in 1881. The ‘poll tax’ was £10, the equivalent of around $NZ 1,700 today was imposed on Chinese migrants and the number allowed to land from each ship arriving in New Zealand was restricted. One Chinese passenger was allowed for every 10 tons of cargo from China, originally before being changed to one passenger for every 200 tons, and the tax increased to £100 ($20,000). Courtesy Archives New Zealand (DADF-D429-19064-1ad)

Figure 6.28: Unidentified photographer: Chinese family in a greengrocery shop, c1920. Since publication in New Zealand Chinese in historical images (2017) Phoebe Li, the NZ Chinese historian, informed me that Turnbull Library staff have identified the photographer as John Reginald Wall (c1870-1944) who had a studio in Stratford, Taranaki. I don’t know if the family responsible for this remarkably tidy shop has been identified yet. (ATL1/2-037 502-G)

Figure 6.29: John B Turner: Yin, Bo & Theresa Ye, M&M Takeaways, corner Te Atatu and Wharf Roads, Te Atatu Peninsula, Auckland, 6 March 2005. This was accidentally dated this ‘11 June 2010’ in New Zealand Chinese in historical images (2017) (JBT027)

Figure 6.30: King Tong Ho: Commemoration of the descendants of Choie Sew Hoy at their family reunion depicted at the Dunedin Railway Station, October 2013. Courtesy of the photographer. A mural-sized print of this picture was featured in the 2016 exhibition at the Overseas Chinese History Museum, Beijing. Courtesy of the photographer

Being Chinese in Aotearoa: A photographic journey

Auckland War Memorial Museum

10 February 2017 - 21 January 2018

Figure 6.31: Installation view of ‘Being Chinese in Aotearoa’ at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, February 2017. (JBT©_20170213-130)

Figure 6.32: Installation view of ‘Being Chinese in Aotearoa’ at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, February 2017. (JBT20170213-148)

Figure 6.33: Installation view of ‘Being Chinese in Aotearoa’ at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, February 2017. JBT©_20170210-083 Being Chinese in Aotearoa exhibition Auckland Museum

Figure 6.34: Installation view of ‘Being Chinese in Aotearoa’ at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, February 2017. (JBT20170213-019)

Auckland Libraries Ngā Whare Mātauranga o Tāmaki Makaurau

I put four questions to Keith Giles, Principal Photographs Librarian at Auckland Central Library:

1. What for you are the big issues that prevent your Library from being more proactive in acquiring collections?

2. What do you think should be done about this?

3. What can photographers do to make their collections more relevant and attractive for institutions to collect?

4. And do you consider this is a crisis in the making, or soon could be unless (what you think could/should be done about it)?

Giles’ response was short, passionate and to the point. He considered it “A very timely enquiry” and his sense of urgency underlines the necessity to take this issue seriously by the government as well as local bodies, that one can argue are not so well-served as those in the capital city.

‘To answer your questions:

1. My policy (following established practice) was always to try to accept whatever collections were on offer, on the basis that it encouraged continuing donations and that if we turned down a collection it might never be seen again’ [my emphasis].

‘The sole issue preventing Auckland Libraries from proactively acquiring collections is space. The library is full, to the point where collections needing a controlled environment cannot even be squeezed into ordinary storage. Collections that we’ve received in previous years cannot be worked on because we don’t have the staff or financial resources to process and describe them’.

2. ‘There needs to be a dedicated repository for photographers’ collections. I think this has to be led by the National Library/DIA [Department of Internal Affairs]. Auckland photographers’ work can only be retained in Auckland if there’s somewhere to put it, and I don’t think there’s the political will to establish any regional storage facility’.

3. ‘A tricky one. I find it difficult when some photographers feel there is money to be made from their collections and want to place all sorts of restrictions on the use of their images. As a public library we want to be able to provide copies to families, researchers, publishers etc. It costs us to safely store and copy photographs. If we have to refer to a photographer or his/her estate or representative for permissions each time someone wants to use a photograph this is an added complication’.

‘Whatever money we receive for providing copies goes towards storage and staff costs. Ideally we would like to receive collections with no strings attached and copyright signed over to us. I know this can be problematic for some photographers. From the photographer’s point of view, I also realise it can be frustrating when some institutions are only able to accept collections on the say so of their Accessions Committee or after a long period of deliberation, when all they want is an instant yes or no’.

4. ‘This is already a crisis, and has been for a number of years [my emphasis]. I know of several collections that have already been lost because of Auckland Libraries’ inability to accept them, because the photographer does not know what to do with their work, and because descendants have been unable to find a repository’.

Auckland Libraries’ basic photographic collections policy aims to concentrate specifically on New Zealand and the Pacific as areas of interest. However, as Keith Giles explains, it's not rigid in terms of geography.

‘For instance, the Ron Clark Collection consists of around 7,000 colour 35mm slides from the 1950s to 1980s. Only around 2,000 of them are specific to New Zealand. This is a problem you touch on in your writing of course. In this instance, whilst it was unlikely that the offer of the collection would be withdrawn if we refused to accept it as a whole, it seemed not only immoral but also an insult to the photographer to suggest breaking it up. Moreover, the whole collection - NZ and non-NZ content - was actually representative of the NZ experience and as such has additional value.

Some years later the wisdom of not breaking up the collection was realised when we came to produce an exhibition called "The Big OE" which drew heavily on Ron's photographs of European trips. For me, this confirmed my belief that collection policies should not be adhered to rigidly and that where possible we should aim to accept whatever collections are offered’. [My emphasis.]

Giles understands, as does Gael Newton, that a body of work that ‘might not be sexy or obviously relevant now may well have an unexpected importance further down the line.’

Lost, broken and damaged collections

Among the “sad stories” Keith Giles mentions are the following:

‘A phone call to John [Jack] Lesnie's widow about his surviving work confirmed that his negatives had been disposed of relatively recently’. [ii]

Figure 6.35: Jack Lesnie: Māori Battalion marching in Queen Street, Auckland c1946. (APL 755-ALBUM-79-0-1) Courtesy Auckland Libraries

Figure 6.36: Unidentified photographer: John (Jack) Lesnie at right with Robert (Tom) Hutchins, news photographers, Auckland c1952. Tom Hutchins Images / John B Turner Collection

Fifi Wynn-Williams worked a professional photographer from Auckland’s Queen Street in the 1930s and Shortland Street during the 1940s, probably under the name of Wynn Williams Studio. She and Frances Gifford ran St. Anne’s School in Takapuna from 1932 to 1971.

Figure 6.37: Fifi Wynn-Williams: St. Anne's School students on Takapuna Beach, Auckland, c. 1939 (T4083). This is a copy of a surviving Wynn-Williams photograph in the Devonport Public Library. Courtesy Auckland Libraries

‘Sadly, Fifi Wynn-Williams dug a hole in the driveway at her house in Takapuna, dumped her glass plates in it and then laid a new concrete drive over the top just to get rid of them. Of the few remaining boxes of Wynn-Williams negatives, several were consigned to the recycle bin before I got my hands on the rest’. – Keith Giles, Principal Photographs Librarian, Auckland Central Library.

Major collections with an online presence:

Figure 6.38: Portrait of woman thought to be photographer Fifi Wynn-Williams, Nd. (AL 1550.1.8). Courtesy Auckland Libraries

Click Kura to browse the Auckland Public Library’s huge heritage database.

Henry Winkelmann Collection: ‘Auckland streetscape glass plates purchased by the Old Colonists' Museum (part of the Auckland Public Library) in 1928.’ The Auckland War Memorial Museum also has part of the Winkelmann collection.

Richardson Collection: an extensive collection of early photographs of Auckland City and surroundings made and compiled by James Douglas Richardson (1878-1942), manager of the Ponsonby branch of the Auckland Savings Bank who was a keen photographer. To help continue his pictorial documentary survey, Richardson worked on it almost full-time after he retired, with the moral and material support of the Auckland Library under the leadership of John Barr.

H J Schmidt Collection: The collection of Herman John Schmidt (1872-1959), of approximately 26,000 glass plates, plus some daybooks, negative registers, and correspondence (manuscript collection NZMS 1347) was saved in 1969. A year later 49 bromoil exhibition prints were donated by his descendants. The Alexander Turnbull Library has a small collection of Schmidt’s negatives also, but his daughter told Keith Giles that the person who bought Herman’s studio spent the first week burning all of the film negatives in the studio grate because they were taking up too much room.

Clifton Firth Collection: The collection of Clifton Firth (1904-1980), negatives and prints, consists of around 100,000 images. It contains his stylish photographs of well-known Auckland identities, writers, musicians, models and the general public. He recorded an era of Auckland's growth - its people, styles, leaders and intellectuals. His trademark, a dramatic blend of light and shadow, was achieved by intense lighting from differently angled light sources. Firth wanted to produce a glamorous theatrical image in the manner of Hollywood black & white still photographers. He established his studio in 1938 with his first wife, Patricia Fitzherbert, and in 1942 Frank Hofmann joined Firth’s studio.

Figure 6.39: Clifton Firth: Auckland War Memorial Museum in construction, c1948. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collection (34-M987A). Courtesy Auckland Libraries

Figure 6.40: Clifton Firth: Maureen Roberts, c1947. Auckland Libraries (920 ROB Display Print, ID 34-355B.) Roberts was a favourite model for both Firth’s commercial fashion work and nude and glamour pictures. Courtesy Auckland Libraries

Charlie Dawes Collection: The collection of Charles Peet Dawes (1867-1947) comprises of 500 plates acquired from a Kaitaia junk shop in 2012, a box of glass plates from a junkshop in Auckland (bought in the 1970s), and a donation of 1,660 glass plates from the family in 2018. The collection has been inscribed in the UNESCO Memory of the World.

Figure 6.41: Charlie Dawes (Attrib.): Detail of the online catalogue entry for this photograph showing the condition of the glass plate negative. Dawes, second from left stands behind fellow photographer Enos Pegler with a camera outside the tent advertising Dawes as ‘Everybody’s Artist Photographer’, with prospective customers and/or friends beside them, c.1910. Auckland Public Libraries’ catalogue description of this undated photograph. Badly damaged through adverse storage, the digital copy of this double-exposed image was extensively retouched for exhibition purposes to restore it to its intended state as a record of the men, their work and time. As is often the case, there may be no original photographic prints from this negative, especially if the photographers were annoyed by its accidental double exposure. (1572-1220). Courtesy Auckland Libraries

Figure 6.42: Charlie Dawes: Detail of the above Dawes photograph showing the masking effect of the partial double-exposure which spoiled the picture well before the physical damage caused by moisture which softened the photographic emulsion and stuck a batch of unprotected glass negative together. (Detail 1572-1220) Courtesy Auckland Libraries

Figure 6.43: Charlie Dawes: The digitally restored and cropped version of the damaged glass negative rescued by the Auckland Libraries as the lead picture for their 2019 exhibition Detail of the above Dawes photograph showing the masking effect of the partial double-exposure which spoiled the picture well before the physical damage caused by moisture which softened the photographic emulsion and caused a batch of unprotected glass negatives to stick together. Note that the normal white and dark spots and dust marks revealed when copying photographs, and are a kind of unintended visual static, have been removed to enrich the visual experience and more accurately reflect the photographer’s intention of making a more refined image (1572-1220). Courtesy Auckland Libraries

Charlie Dawes photographed the people and communities of the Hokianga at a time when the area was at the centre of New Zealand’s timber industry, and before the arrival of cars and intensive farming. The collection includes many formal portraits, but more importantly Dawes often captured his neighbours informally at work and at play in Kohukohu and Rawene for example. He was a jack-of-all-trades, working variously as a carrier, mailman, nightsoil collector and orchardist and was active as a photographer from at least 1892 to around 1925.

Rykenberg Collection: John Rykenberg (1927-2014) emigrated to New Zealand from the Netherlands in the 1952 and established a successful photography business in Auckland. He took pictures on streets, in restaurants and on the wharves as well as shooting weddings and other social events. He inherited or collected thousands of NZ photographic negatives by other, often unidentified photographers. The Rykenberg Collection consists of well over one million images, of which more than 15,000 have been digitised and published on the library's online database.

The 1990 Project: In 1990 the Auckland Libraries commissioned five photographers to make documentary photographs of Auckland city and surrounds as part of the nationwide New Zealand Sesquicentennial celebrations. The photographers chosen were Miles Hargest, Chris Matthews, Paul McCredie, Stuart Page and Ans Westra and the task of putting the work of all five photographers on-line was completed in 2022.

Figure 6.44: Miles Hargest: Avondale Wholesale Meats, Great North Road, Avondale, Auckland 1989. The 1990 Project (273-HAR001-09). Courtesy Auckland Libraries

Figure 6.45: Stuart Page: Cow on Mount Wellington, Auckland 1989. From the 1990 Project (273-PAG008-04). Courtesy Auckland Libraries

Lost collections:

‘Dennis Hamblin told me that when institutions showed no interest in his negatives, he took the drastic action of destroying them to recover the silver they contained.

‘Although I agreed to take Rob Newbiggin's negatives, by the time he came back to me several years later we had no storage space left for a collection of the size he was offering. We finally compromised on accepting a single banana box of his work. I didn't dare ask what had happened to the other 22 boxes.

Giles was not surprised to hear recently, that somebody who had worked in both museum and archaeology roles said that they were always conscious as an archaeologist not to aim to dig up every last artefact because that would only create problems for the museum curators!

While the logic behind that decision seems perverse, the disincentive to make tasks more difficult or unsurmountable is a reality, and one can only wonder if it is shared by the powers-that-be as an easy way of letting aspects of our photographic heritage destruct through neglect as a means of self-preservation when they lack the support to properly fulfil their responsibilities for posterity?

Sally Symes Collection. The good news, Giles reports, is that Sally Symes' negatives from her collaborative essay, the Te Hapua Project, of 1977-79, are now held by Auckland Libraries: ‘We've digitised these and we currently have a team of Māori librarians working on descriptions and metadata. The rest of Sally's collection is still with her family.’ [iii]

Sally Symes (1945-1995) was the Director of Photoforum Inc in 1989-93. Her personal collection will undoubtedly include photographs from her extensive overseas travels including South-East Asia and East Africa, which almost certainly would have some relevance in the future, if not now, in relation to the history of our African and Asian refugees and immigrants, just as Tom Hutchins’ photographs of China in 1956 embody a NZ sensibility, encourages comparison of living conditions, and remind us of aspects of New Zealand’s contact with that then poor and devastated nation which is now a thriving economy and major participant in international affairs.

Additional online links: A list of Auckland Libraries on-line exhibitions includes those of Charlie Dawes, Clifton Firth, the Tornquist brothers and the Dominion Road Project, a series of oral histories, supported with photographs by Solomon Mortimer.

I know of many personal collections that would fit into the collecting criteria of the Auckland Libraries and the Auckland War Memorial Museum, including my own and that of Tom Hutchins, but it does seem that the Auckland Libraries, at least in the central library, have reached capacity in terms of storage, facilities and staff and can’t seriously contemplate taking in more collections under their present circumstances.

I have shown glimpses of some work from collections in limbo that have yet to find a home and are therefore in danger of being lost in part or whole. There is an urgent need to identify the most significant collections in this situation, nationwide. We can’t assume that the photographers who should be concerned about the future of their work will know who to approach, any more than expect librarians, curators and archivists to seek out their work when they have more than enough of a backlog to work with.

Figure 6.46: John B Turner: Youth group, corner of Te Atatu and Wharf Roads, Te Atatu Peninsula, Auckland, 6 March 2005 (JBT056a). From Te Atatu Me: photographs of an urban New Zealand village by John B Turner (2015). Photographer’s collection

Figure 6.47: John B Turner: Young men in 2005 photograph (Figure 46 above) visit the photographer's exhibition at Abundance Art Gallery, Te Atatu Peninsula five years later. Auckland, 10 July 2010. (JBT054b). Photographer’s collection

Brian Donovan's Then & Now project