Charles McKenzie - essay

The Boundedness of Familiar Strangers – Charles McKenzie’s People of Parnell

An essay by Nina Seja for PhotoForum, March 2021

There’s a connectivity that happens between people when you acknowledge each other on the street. It’s something particular – unique – to the circumstances of the encounter. The location, the moods of each party, the weather. When a camera is involved, there’s an element of trust, the degree to which is revealed in the image. The subject’s openness, ambivalence, or reluctance is there in the frame.

I’ve wanted to write on Charles McKenzie’s early 1970s Parnell photographs since I discovered them when writing PhotoForum at 40. There was something caught in the photographs that felt without artifice, each interaction distinct. The images affirm a spectrum of human relationships, their intimacy a gift to those who witness it.

While living in Parnell, Auckland, Charles McKenzie was able to survey, out his apartment window, the development of the main drag as it changed in 1974. Being walking distance to the University of Auckland and an inner-city suburb, this was a time of Parnell coming into its own as a night-life hotspot. As with my 2019 essay on Clive Stone’s Hibiscus Coast Project, we are presented with changing social landscapes. (1) The down-to-earth Parnell of McKenzie’s work represents the soon-to-be gentrified upmarket Auckland suburb. It’s vital that these histories – made all the more potent by being visual – are part of public memory. They show that a city is not static, its energy not contained by rigidly enforced, unchanging social lines. (2)

The photographs that make up Urban Environs – People of Parnell ’74 show the value of unearthing material from personal archives. By doing so, photographic history becomes that much more all-encompassing and offers a more substantive discussion across a greater time span of image history. We’re able to see the influences and networks – pedagogical and artistic – that have shaped a photographer. Importantly, disseminating them by way of a public, ongoing digital platform continues the life of the images, an increasingly vital conversation to be had about how we can ensure New Zealand’s photographic legacy is not lost. (3)

Studying at the University of Auckland, McKenzie’s Bachelor of Fine Arts papers included photography classes with Tom Hutchins and John B. Turner, critical figures and encouragers in New Zealand’s photographic genealogy. (4) One assignment was documentary in nature, with John B. Turner encouraging McKenzie to pay attention to his immediate surroundings, and to consider photographic history through the likes of practitioners such as August Sander and Lewis Hine. Sander’s direct gaze and social palette that depicts a cross-section of society is notable in Urban Environs. From rough and ready students to stern older men, from nuclear families to professionals in charge of our way of the earthly state, McKenzie’s city-fringe Auckland residents are a reminder that humans are, by nature, heterogeneous.

Parnell in this time period had its ramshackle houses. In one image, a young family stand outside their home, the overalled father, cigarette held casually in hand, smiling at McKenzie. The pregnant mother, likewise, has an expression of openness – like that of greeting a neighbor. McKenzie had wandered the back streets of Parnell to find subjects, and the sense of homeliness is apparent. He meets another family in a supermarket, both the building and fashion for adults and children gone in the midst of time. At the old stone library and lecture hall facilities on Parnell Road, a neighborhood bruiser – the local paper boy– munching an apple gazes down at McKenzie in a low-angle shot. “He knew exactly how he wanted to pose,” McKenzie says. This giving of subjects the autonomy to pose how they liked is a significant element that cultivated a sense of trust.

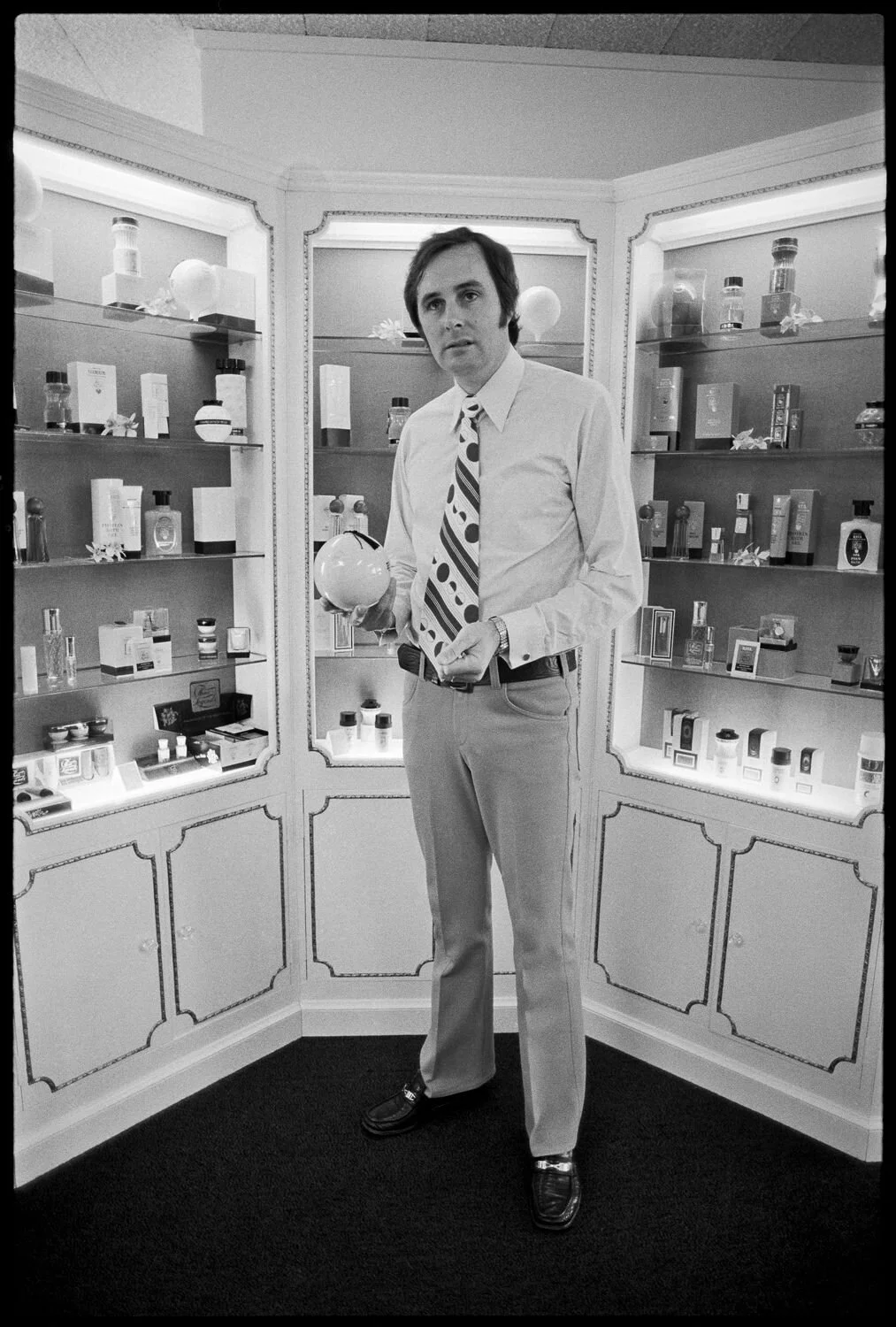

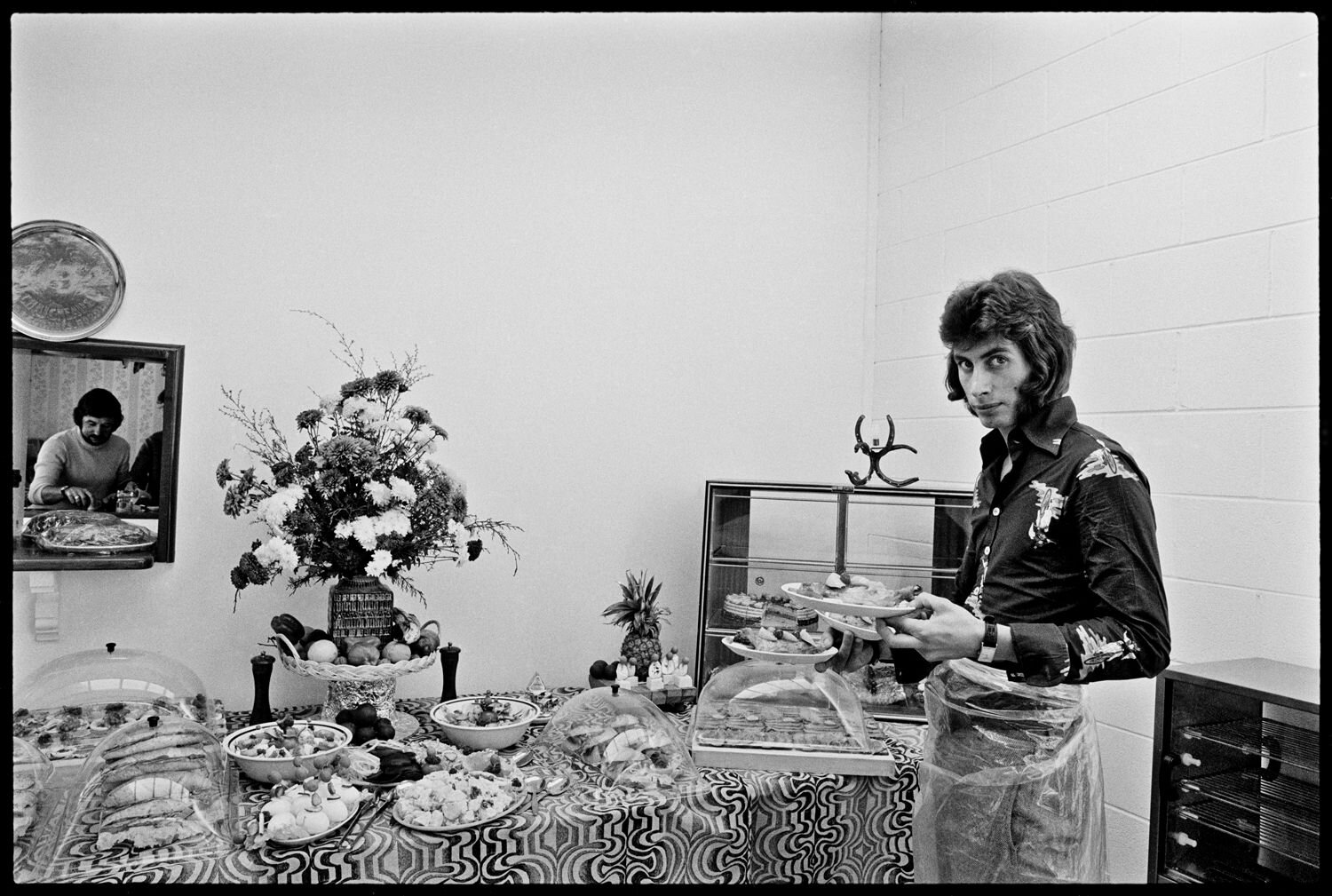

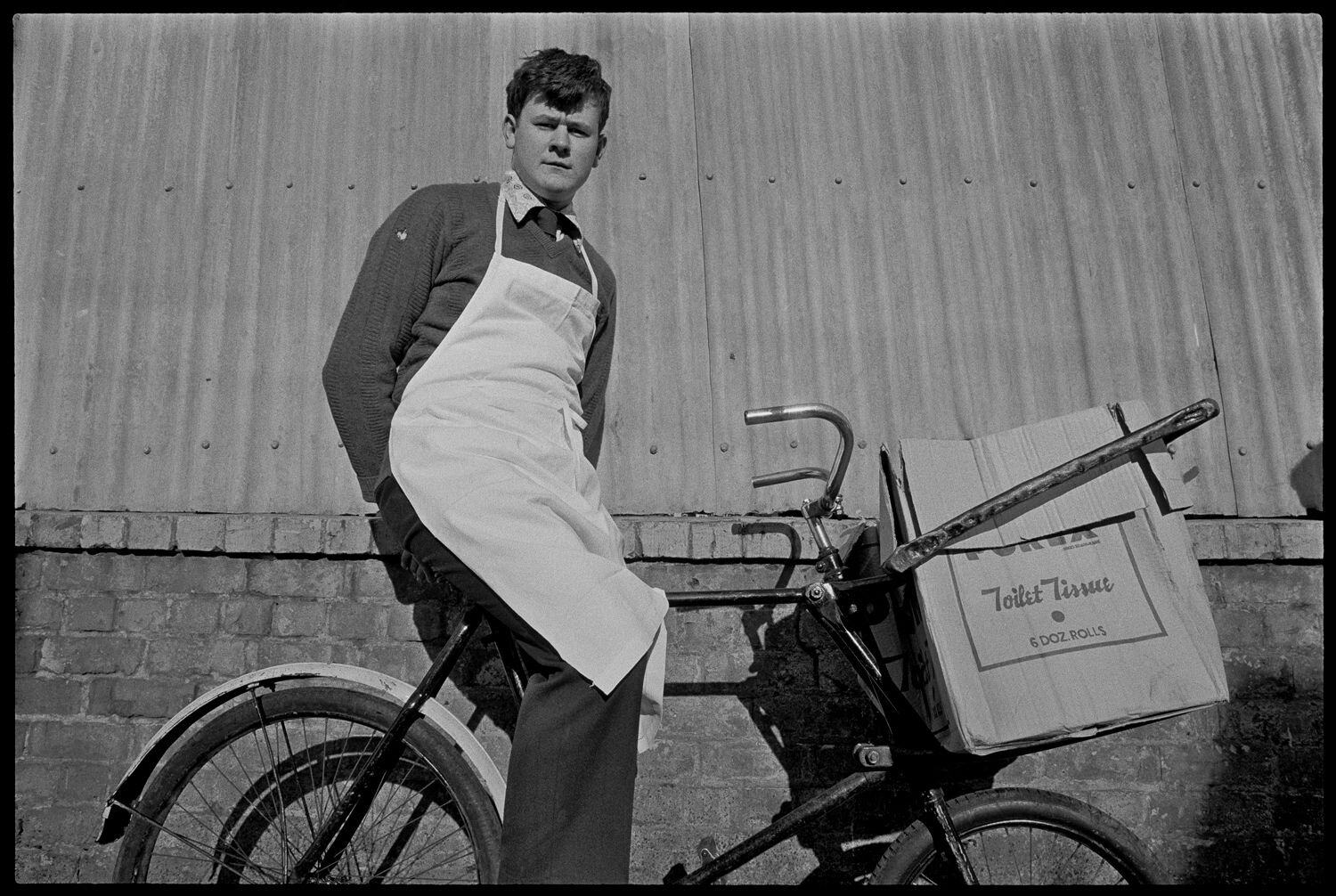

In other photographs, the locals proudly display their wares, their occupations notable not only by their outfits but also by the tools of their trade. McKenzie’s use of a wide-angle lens takes in the subjects’ surrounds, the environment a natural extension of their roles, some of which seem like relics from a different age, as with the grocer in his white apron and his similarly-aproned helper on a bicycle, making local deliveries. In another image, the hairdresser’s buoyant gaze welcomes the photographer into her space. Hairdressers are often considered ad-hoc therapists – the rapport between them and their clients forming a sacred ritual. The familiarity here expands to include McKenzie.

Cars play an important part in how some wanted to be represented. “The undertaker insisted he have his photograph standing in front of his hearse.” The subject, clearly a man who enjoys his job, beams beatifically. Though, as McKenzie notes, “I didn’t notice until later that his finger is pointing down to the ground.”

It’s important to highlight, too, the details that ground Urban Environs in a particular time period. The textures take us back to the glory of the ’70s, when bold psychedelic abstracts took hold. They form the background to the hair salon, a tea lounge tablecloth, carpets, the pharmacist’s tie and the deco cabinetry behind him. Even the eager Mormons in the takeaway joint sport wide patterned ties. Photography, in this way, also records the settings that frame daily routines, inconspicuous until seen through the distance of many decades – then the bold geometric wallpapers and furnishings truly show their personality.

As a form of visual heritage, Urban Environs is a testament to the need to both mine the archives and share the bounty so that we come to know our histories to a much richer degree. Charles McKenzie’s Parnell neighborhood reminds us of the inevitably of change. But it’s also a tribute to the lives that form impressions on us as we go about our day, and to this, the boundedness of familiar strangers.

Nina Seja is a writer and researcher based in Auckland. She extends warm appreciation to Charles McKenzie for his time and enthusiasm during the writing process, and in the conversations that began during PhotoForum at 40.

Footnotes

(1) For a selection of Clive Stone’s portfolio from this series, see “Summer’s Lease: Clive Stone’s The Hibiscus Coast Project,” PhotoForum, October 2019, https://www.photoforum-nz.org/blog/2019/11/1/clive-stones-hibiscus-coast-revisited-essay

(2) For example, Henry Chalfant’s photographs from New York City in the ’70s and ’80s depict the city in a time of economic decline but also grassroots cultural expression. For his images of graffitied subway cars, see Valeria Ricciulli, “Subway Photographer Henry Chalfant’s Photos of ’70s and ’80s NYC Documented in New Exhibit,” Curbed New York, September 30, 2019, https://ny.curbed.com/2019/9/30/20891490/bronx-graffiti-hip-hop-history-henry-chalfant-photos.

(3) Of photographer Tom Hutchins’ work, John B. Turner writes, “Among the disintegrating cardboard boxes of damaged papers, publications and manuscripts found by Mala Mayo and myself under Tom Hutchins’ Remuera, Auckland house early in 1989 were around 600 rotting Agfa Brovira 8x10 inch prints made for his intended book on China.” See John B. Turner, “Seen in China, 1956,” Photography of China, https://photographyofchina.com/blog/tom-hutchins

(4) Read more on both photographers in John B. Turner’s “PhotoForum: A Personal Reminiscence,” and Tom Hutchins’ obituary, both in my 2014 book PhotoForum at 40 (Auckland: Rim Books, 2014).

We need your help to continue providing a year-round programme of reviews, interviews, portfolios, videos and listings that is free for everyone. We’d also like to dream bigger with the services we offer to photographers and the visual arts, including more payments for artists and opportunities to foster new projects and exhibit them online.

We’ve partnered with Press Patron to give readers the opportunity to support the PhotoForum Online programme.

Every support donation helps.