Jenny Tomlin - Featured Portfolio

Jenny Tomlin

PhotoForum Featured Portfolio

Essay by Nina Seja for PhotoForum, November 2020

An Unhurried Bounty – Jenny Tomlin’s Solargrams

“I wanted the images to convey the feeling of immersion and drainage, of being stuck in that sucking mud.”

Jenny Tomlin, Mangere Crush, 04/03/09 to 11/05/09

So unusual is the attempt to slow down life now that it can result in a flurry of articles, movements, and turning slow-movement spokespeople into celebrities. There’s even a genre called slow television, first popularized in Norway. Photography, though representative of stillness in any case, has a genre that also embraces slowness, through solargrams. These are, traditionally, six-month exposures from the shortest day to the longest or vice versa. The exposure period marks the sun’s journey across the sky. Other seasonal changes are also imprinted, like leaves falling from a tree.

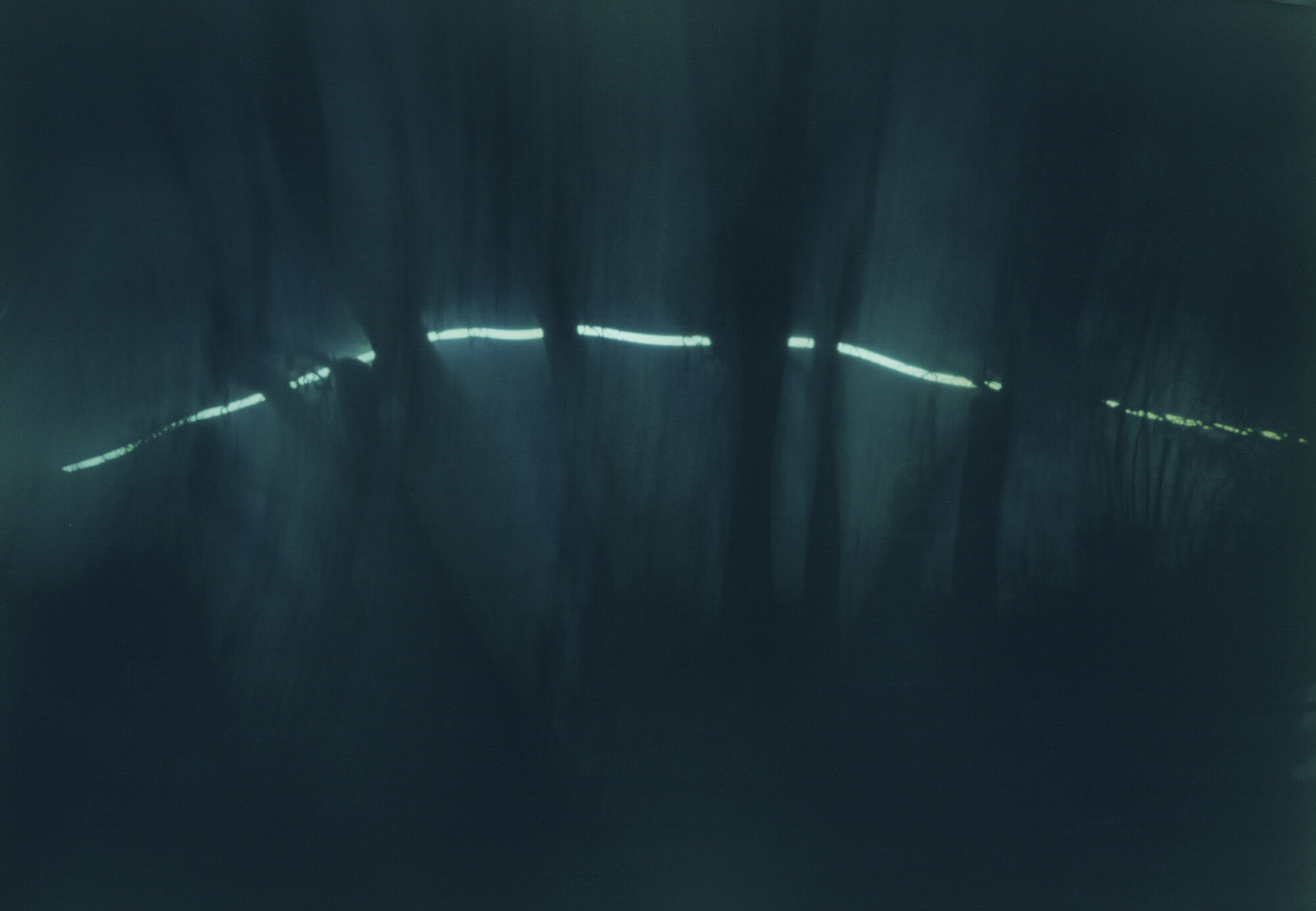

Photographer Jenny Tomlin uses solargrams to chart incremental shifts in nature that, when recorded over many months, reveal the intricacies of natural life changing around us. The end result is like the invisible made visible as the sun rests low and then high in the frame – a glowing band of light. Tomlin does say, though, that she “was initially surprised at the lack of detail in the landscape. The longer the time, the recognizable elements are less defined – time smoothing out the bumps and kinks – an extreme version of the streets devoid of people in nineteenth-century early long exposures.” This compression of time into a single image is what drew Tomlin to the process.

The extended making process is a critical part of the overall process for Tomlin’s work – it could, in fact, be seen as art (and performance) in its own right. Because solargrams capture the shifts of nature, Tomlin’s work is simultaneously epic (operating on a large scale, with planetary shifts in seasons) and focused on the micro – a “sitting in the moment” as time passes. Tomlin’s work is notable for its quiet landscapes and highly textured environments. Nature’s palette is subtle in its gradients. The longer exposures, particularly in scenes from the photographer’s garden, means the “sense of time passing as well as the coming together of the elements is unique each time and won’t happen the same again.” With some set against the backdrop of the pandemic, Tomlin acknowledges that “Lockdown intensified this.”

Jenny Tomlin, Flight, East Window.

One image, taken at the beginning of lockdown in March for a five-month duration, shows a view outside of the photographer’s window. The chemical damage of the paper adds in additional layers to the already ethereal qualities – chemical spots becoming stars and a dart.

Tomlin’s gaze also repeatedly returns to the magnolia in her garden. Wrapping around several windows, the photographer could see it from the kitchen, dining room, and bedroom. Tomlin says that she “never gets tired of its constant change through the seasons. It’s almost a muse for me – or an archetype.” Nature is a tethering post.

Jenny Tomlin, Magnolia, 29/05/19 to 31/10/19

Jenny Tomlin, Whau River, KM bridge, 15/07/19 to 07/07/19

Whau River, KM bridge camera location, 19/06/19

The locations of the solargrams also encompass the Whau River in Auckland’s Waitematā Harbour, whose personality is slow moving, thick with sediment and mangroves. “As well as needing to generally face north, I look for something that will be affected by the seasons or weather,” Tomlin says. “The Whau River has been a particularly rich environment to work in. It varies a lot between the feeder creeks on the Manukau side then getting wider as it enters the Waitematā and I was unfamiliar with it; scouting its many nooks and crannies for the first time. The spots are often quite hard to access because I don’t want them disturbed.”

There’s a physicality to Tomlin’s photographs – the tidal works, particularly, feel very “bodily”. You can sense the flows and receding of the water in them, and the feeling of being submerged. In this way, the images become almost cinematic, in that the time “lapse” occurs and the viewer moves through time, though in a single image. Stillness, floating, mangroves brushing the ankles – the presence of nature is immediate as well as sensual. The different textures convey the rhythms of nature of which we are a part.

Tamaki Tidal camera location, 26/05/20

This was Tomlin’s intention from the beginning of the project in terms of what she wanted to achieve. She was hoping for tidal effects on the paper negative in the camera. “I’ve always had a fondness for mangroves, the way they take over that edge between the sea and the land, their aerial roots breathing in the air or water rather than the mud.” These works harken back to Tomlin’s earlier work of forgotten and forsaken spaces, like those “of an industrial area of Westfield (1984–5) on the Manukau Harbour with mangroves and salt marshes reclaiming the space.”

Patience is a central part of the process – the rhythms of nature cannot be hurried, and so the photographs become blueprints for the changing seasons. Tomlin says “the waiting is difficult. The anticipation gets so intense, I need to use self-control not to remove them too soon.” This became even more so for a group workshop she led: “It was most extreme at the Whau as it was part of a group workshop project and I felt responsible for the participants’ cameras and went many times to recheck the cameras were still in their spots.”

The latter part of the process is also in-depth, immersive. “The scanning then inverting the image to a positive is a particularly intense aspect of analogue photography for me. All the waiting, then a single pass of the scanner simultaneously captures the image and degrades it. There’s one chance to get it right. Lots of disappointments and a low strike rate but the good ones are worth it.”

An additional layer is that formed by expired paper. What would be considered disposable is instead repurposed and valuable. Over the exposure period, the paper reacts to the environment – “water or mould changing the emulsion is an important parallel performative part,” Tomlin says.

There’s an underlying subtlety to the process too, with the camera itself becoming a part of nature over many weeks or months – hidden to those who may pass by. There’s something satisfying and somewhat rebellious in an era of ubiquitous cellphone snaps and the ever-present drone of surveillance recording to have slow photography remind us of the enduring beauty of the natural world. And more than this – they take us further on the journey when nature rewards our attention with an atmospheric magic.

*

Nina Seja is a writer and researcher based in Auckland.

Jenny Tomlin is an analogue photographer. Her work moves between medium or large format landscapes through to alternative slow light processes of pinhole photography, solargraphy, and lumen printing. These solargraphs are an exploration of how things change yet stay the same over time, a celebration of serendipity overlaying expected outcomes.

Based in Waitakere, Auckland, Jenny completed a Fine Arts degree at Auckland University in 1984 and has worked as a darkroom printer in NZ, Australia and the UK. Since 2002 she has run a black & white darkroom, printing for film photographers, holding workshops and exhibiting her own work.

To see more:

Instagram: jenny_camera_obscura

FB page: JennyTomlinPhotographics

www.jennytomlin.co.nz

contact: jen@jennytomlin.co.nz

Published with support from Creative New Zealand.