Cathy Tuato’o Ross and Ellen Smith - featured portfolio

Partial Loss: Exercises in Reduction

Cathy Tuato’o Ross and Ellen Smith

Essay by Andrew Paul Wood

PhotoForum featured portfolio, May 2019

Raised in Wellington, Ellen (Ellie) Smith now lives in a small coastal community at the head of Whangarei harbour with her partner, dog and chickens. She is interested in the cameras ability to force us to re-look at, and make significant, the things and places which surround us but are so familiar they lose visibility. Her latest work explores combinations of digital, natural light and darkroom processes. Ellie exhibits locally and nationally, runs community art projects and works commercially as a photographer of exhibitions and artwork. She also works part time as one of the photography tutors and gallery co-ordinators at NorthTec.

Cathy Tuato’o Ross lives in Parua Bay, Whangarei, with her partner and their four daughters, where she works from her home studio. She exhibits nationally, teaches drawing and works as a freelance writer. In 2010 she was awarded a PhD from the University of Otago.

Among other things, Cathy's work explores people's relationships to objects and images in their lives and their homes. Of particular interest is the transfer of things, by means of gifting or bequeathing, for example. She is interested in both the types of objects and images that circulate, are selected, reproduced, kept and treasured (or otherwise) and in the meanings and significance that are bestowed on these objects/images.

VANESSA IVES: “Do you have a favorite?”

ALEXANDER SWEET: “Not meant to. But mostly the unloved ones. The unvisited ones. The cases that get dusty and ignored. All the broken and shunned creatures. Someone's got to care for them. Who shall it be if not us?”

- Penny Dreadful, Season 3, Episode 1, “The Day Tennyson Died” (2016)

It has been said that capitalism makes people into things, and animism makes things into people. There is a fundamentally animistic sensibility underlying Cathy Tuato’o Ross’ and Ellen Smith’s diligent cataloguing of nostalgic waifs and strays of nostalgic cultural detritus making up Partial Loss: Exercises in Reduction, presented in sharp aesthetic sensibility with wistfully ironic titles. These relics are concrete stories that have a mysterious pull to them, they cajole us into caring about them.

One concept this project evokes is the “salvage paradigm,” an anthropological term of the early twentieth century for the idea that cultures perceived by the West as “weaker” must have its authenticity protected and preserved by the dominant culture even as that dominant culture corrupts and destroys it. More recently this idea has been heavily criticised for its implicit Western ethnocentrism and failure to recognise the capacity of other cultures to adapt and respond, but what if we turn that gaze back on our own recent artefacts and the feelings they evoke. The sentimental gaze is all too often dismissed, but is nonetheless an authentic emotional, human response – an act of existential self-preservation in an otherwise arbitrary and disinterested universe.

There is a distinctly anthropological/museological gaze at work here. The objects are presented on their own against a blank background like a specimen for study. The objects are imaged on a flatbed scanner, which slowly peels back strata of archaeology: each object tenaciously clinging to its distinct psychic aura or presence and social context, their public and private significance persisting down the corridors of time beyond their use. They are talismanic fetishes that can be put out of mind, hidden away out of sight, but can never be disposed of. They are nodes that tie us to memories, to genealogies, to relationships we barely understand. Some are significant simply because they have endured the vicissitudes of fate even if all other context has been lost. There is often a poignancy and pathos to them.

The use of the scanner rather than a camera to make the images has a peculiarly flattening effect, particularly on the bulkier objects, and introduces a uniformly dulling and subdued effect that is as full of subtle pathos as it is utilitarian. Scanners are not uncommonly used that way by harried museum cataloguers trying to seed up the databasing of accessioned items, but here it has become an aesthetic.

And I have seen dust from the walls of institutions,

Finer than flour, alive, more dangerous than silica,

Sift, almost invisible, through long afternoons of tedium,

Dropping a fine film on nails and delicate eyebrows,

Glazing the pale hair, the duplicate grey standard faces.

- Theodore Roethke, “Dolor”

We might recall the minimalist challenge often attributed to Ernest Hemingway, of the shortest short story possible: “For sale: baby shoes, never worn”. These photographs seek to pack a similar amount of information and ambiguity into a compact format. As with any Aristotelian exercise in the encyclopaedic and museological, Partial Loss condenses categories to representative types in attempt to define different kinds of subjective, ineffable feeling of objects that are immediately familiar. This is the reduction of the subtitle, the minimum concrete signifier a whole ecosystem of complex human, social and psychological relationships can be condensed and attached to.

The objects in this iteration of Partial Loss: Exercises in Reduction are connected in a rhizomatic overlap that isn’t immediately obvious; a Foucauldian genealogy, a Wittgensteinian web of disparate “family resemblances”. There are two loose groups: the commemorative bric-a-brac of marriage, and trophies and awards that represent minor triumphs in life’s quotidian mundanity. When we tune into the artists’ logic we can see how marriage can be, benignly or cynically, be viewed as a kind of competition (with the world, time, family, economy, each other) for which society awards prizes, especially when these objects were new. In the end we are all competing with time and oblivion, which puts these images firmly in the vanitas tradition – sic gloria transit mundi, the glories of this life are swift in passing.

Most of the objects depicted date from the first half of the twentieth century when marriage was the norm and expectation of life, shimmering with a romantic lustre that twenty-first century capitalism and cynicism have done much to commodify and make disposable. Why should the decorations of a wedding cake or an engraved tray commemorating a wedding anniversary be seen as any different from a trophy cup or a medal? Especially when they are made of, or pretend to be made of, the same material: silver.

The preciousness of silver makes it an appropriate gift to mark the slowly vanishing rituals of life – christenings, first communions, twenty-first birthdays, weddings, and twenty-fifth wedding anniversaries and jubilees. Like the photograph itself, such an object preserves a moment in time, an emotional charge that fades with time and distance until the value lies chiefly with the preciousness of the material itself and its display to a public gaze until they eventually take on the mantle of memento mori. If that’s the case, does the integrity of the form really matter, not least because since the mid-nineteenth century it’s more than likely to have been mass-produced and picked out from a catalogue.

Silver’s shiny purity is full of optimism, but as silver ages follow golden ones, silver medals and trophies suggest second place, Salieri to someone else’s Mozart. Increasingly silver is less an achievement than an award for participation. As the stakes descend, everyone’s a winner (and more often than not, silver-plated nickel or plastic). Partial Loss filters these artefacts through Marcel Duchamp’s readymades, and Neo-Geo and commodity sculpture and presents them encyclopaedically in a similar way (though not quite as obsessively) as Bernd and Hilla Becher accumulated their photographs of water towers and other human constructions.

When one looks at these things that were once precious to someone, one can’t help but feel voyeuristic, even as their aestheticization as art object attempts to defuse and exorcise that aura of privacy. Perhaps the most obvious method (already established in practice by other photographers) is the distance created by the act of photography or scanning itself, re-categorising intimate memorabilia to objet trouvé. This has the advantage of refocussing the viewer’s attention on the aesthetic details, especially when outside of sentimental attachment these objects are more or less functionally useless.

J'ai plus de souvenirs que si j'avais mille ans.

- Charles Baudelaire, “Spleen”

Yes

You have come upon the fabled lands where myths

Go when they die,

But some, especially the Brummagem capitalist

Juju, have arrived prematurely.

- James Fenton, “The Pitt-Rivers Museum, Oxford”

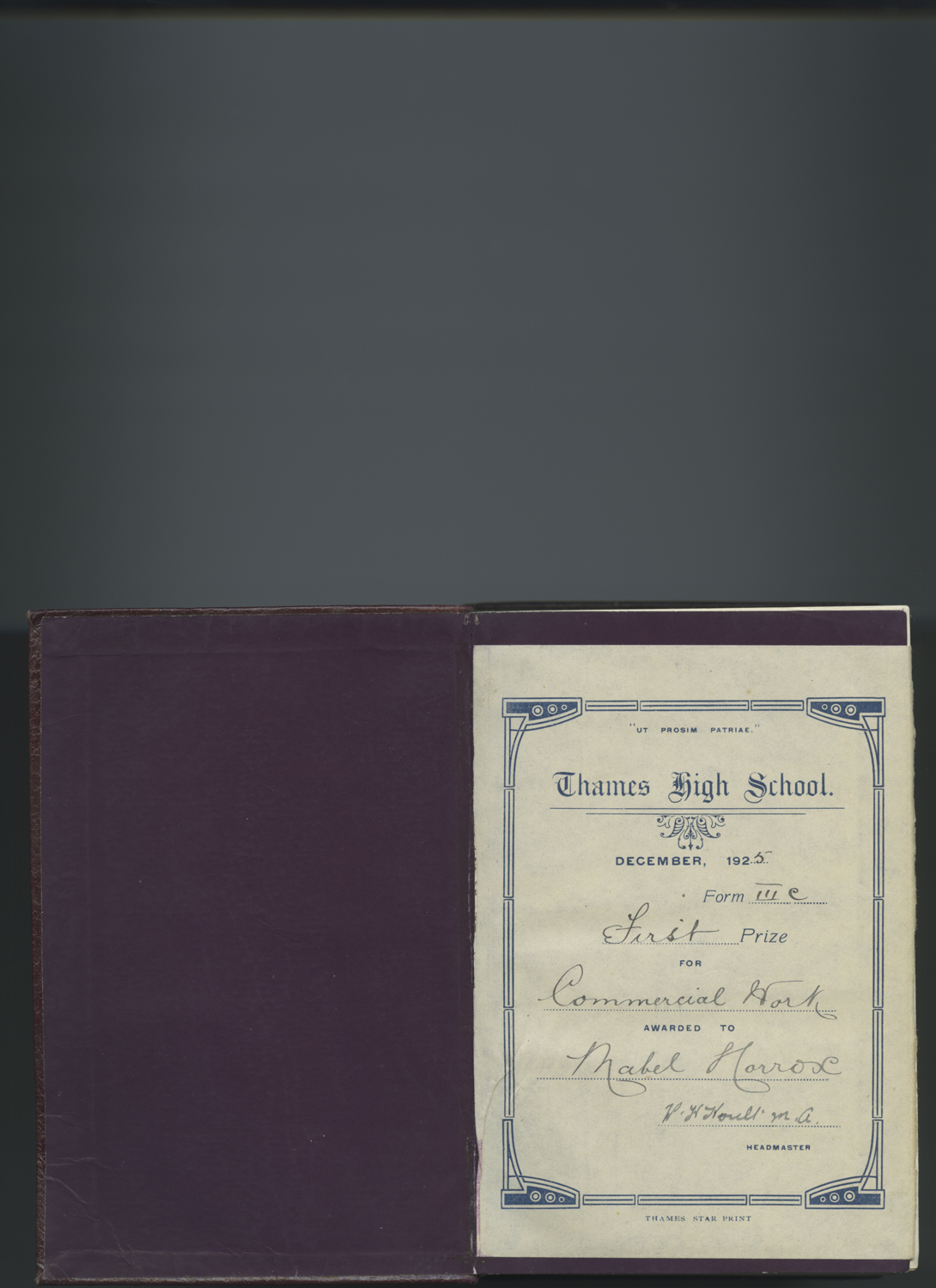

Objects with text introduce a further element of meaning. A china plate inscribed “Father”, a book plate announcing it was a school prize long ago. What's Hecuba to me, or I to Hecuba? Look upon these works, ye mighty, and despair. These hint at names and relationships that meant something to someone sometime. Now it is only a stylistic choice, a design, an example of fine penmanship.

Ashes to ashes, dust to dust, to settle as a second skin on tchotchkes on the mantle and the shelf. In a way these things are a kind of Pākehā taonga that links back to distant European origins and traditions. With every death of an older relative, with every house clearing and divvying up, once treasured heirlooms and mementos find their way to op shops and TradeMe. It is fortunate that Cathy Tuato’o Ross and Ellen Smith have shored these fragments of shadow lives against our ruin.

Andrew Paul Wood is a Christchurch-based independent cultural historian, art writer and critic. He writes for a number of publications including Art News New Zealand and Art Monthly Australasia. He was co-translator (with Friedrich Voit) of two collections of the poetry of Karl Wolfskehl, and is art and essays editor at takahē magazine.

Ellen Smith and Cathy Tuato’o Ross are both represented by Photospace Gallery