Stu Sontier - featured portfolio

collapse

Featured portfolio by Stu Sontier

Essay by Andrew Paul Wood for PhotoForum, December 2019

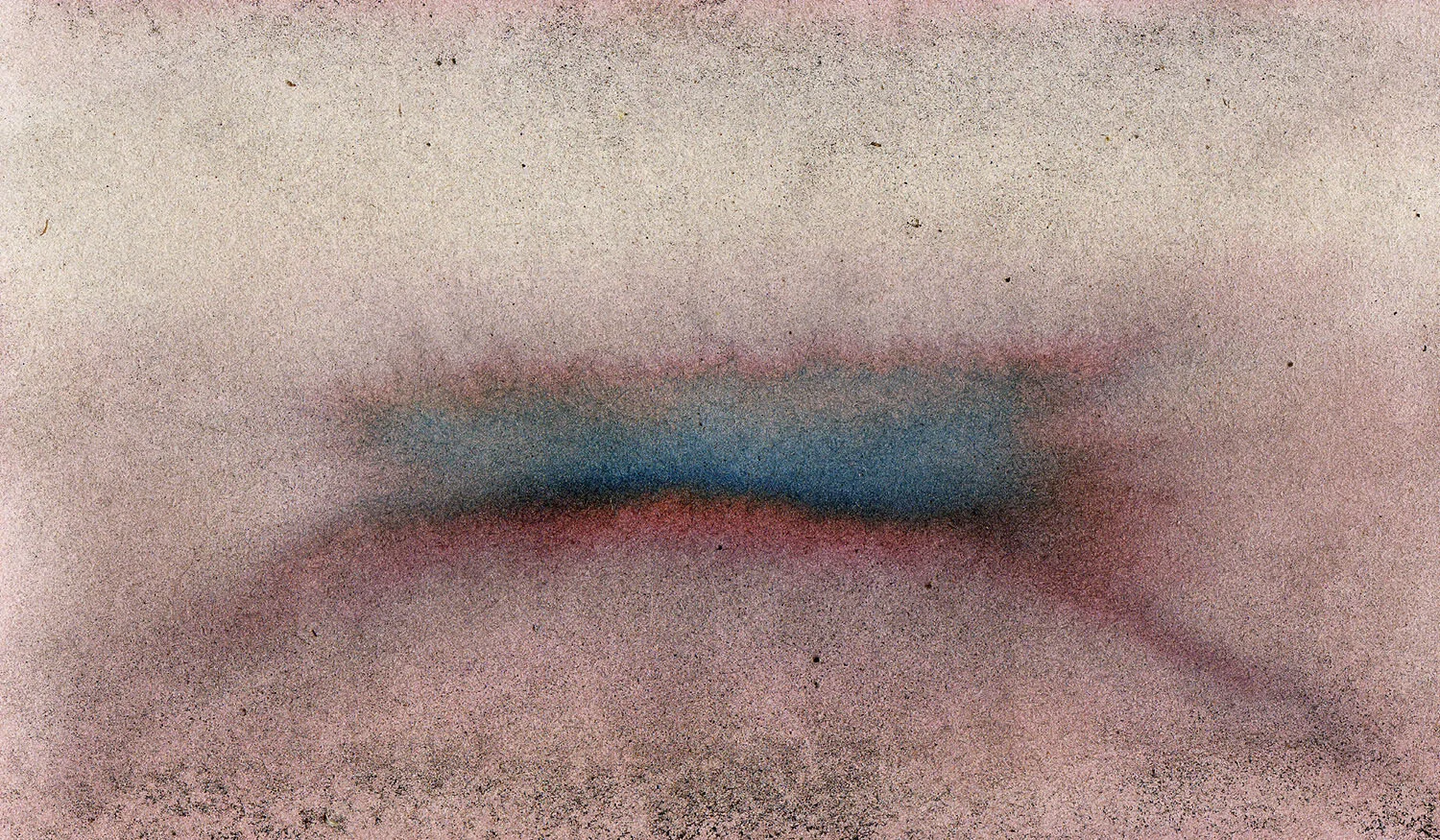

Stu Sontier, collapse - untitled (waste ink wip #3)

When Rosalind Krauss wrote “Sculpture in the Expanded Field” in 1979, it was one of the first attempts to describe postmodernism as a cohesive logic rather than a grab bag of eclecticism, noting the “permission, or pressure, to think the complex”. Traditional categorical hierarchies dissolved, and art moved into the spaces between. On this side of the digital revolution the same can be said of the relationship between painting, photography and two- and three-dimensional printing. In collapse, Auckland-based artist Stu Sontier explores this territory in seeking out the interesting analogue happenstances that emerge from the glitches, breakdowns and manipulations of digital technology. Old papers, faulty printers, re-photography, broken lenses and other damaged materials and components result in outputs that mimic the expressive gesture of the artist’s hand.

“On a basic level,” says Sontier, “I identify as a photographer and understand that language the best, so I consider my work to be in that realm even when it might appear to stray. To apply terminology and categorisation (as important as that is) is to potentially close down avenues of exploration, so when I start to worry about whether it is photography, I remind myself that I can leave it to others to ponder this – it’s not really my problem. I find it useful to be reminded of photography’s history – camera-less and experimental processes as well as the dead ends (often for commercial reasons), as well as looking at recent boundary-pushing work and the writing of the likes of Charlotte Cotton, Susan Bright and such books as ‘Why it does not have to be in focus’ by Jackie Higgins, along with various recent books and exhibitions on camera-less photography including Emanations, curated by Geoffrey Batchen.”

How does photography retain cultural relevance since digital manipulation shattered (in the public imagination at least, photographers honest with themselves have always known the process to be manipulated inside and outside of the camera) the contract with realism? Perhaps through looking at how painting responded with impression and abstraction to photography’s usurpation of visual primacy, an interrogation of the relationship between the digital and the analogue rather than a confrontation but looking cautiously forward rather than nostalgically back.

“The recent revival in old and alternative processes,” says Sontier, “is happening at just the time that such things were about to be lost to digitalisation. It fascinates me though that ‘alternative’ processes only appear to allow a looking back, and often reject the newer materials as inferior, and anything to do with pixels. Andreas Gursky’s pixel-pushing is allowed because it still looks analogue. Anything that looks too digital still suffers from an aesthetic bias, although I personally find that a lot of the recent digital work remains a bit clunky and unformed as to where it is going. More interesting perhaps is the mannered investigations of Thomas Ruff, which David Campany refers to as the “Aesthetic of the Pixel”. Ruff is clinical but realises the difficulty and simplicity in transitioning to digital work.”

We detect in Sontier’s work an ersatz painterliness which is the surface of its appeal, but this is backed with rich intellectual questioning and connection to the physical world of its generation, as well as the Romantic-Modernist sense of the transcendental and the possibility of the Sublime, which is often regarded with suspicion in postmodernism, a Borgesian approach to the labyrinthine infinite that seems cousin to Dane Mitchell’s approach to knowledge. Sontier creates his own logic in his approach to technology and creates his own systems of visual knowledge.

“The underlying motivation of the project and much of my work,” says Sontier, “is based around an interest in the physical sciences and the environment. Collapse can refer to classical quantum theory and the notion of wave function collapse, to the possibility of climate tipping points and to current problems with bees and colony collapse disorder. The physical sciences have been attempting to describe the universe in ever more detailed ways, but to a layman it can seem that theoretical physics is currently delving into very esoteric areas and competing explanations are both captivating and currently unprovable.”

The limits of the knowable and the impulse to circumvent aesthetic restrictions through the random and procedural has been of interest to artists at least since Duchamp. This seems to be particularly important in our culture saturated in disposable spectacle as predicted by Walter Benjamin in his Arcades Project (1927-1940, first published in 1982). Flaws provide a kind of authenticity, a stamp of realness and humanity. In literature there is found poetry extracted from mundane prose, and the cut up. Glitchcore music, for example, relies on what is often called an “aesthetic of failure”, incorporating glitches in audio media and sonic artefacts to make sound art. New Zealand artist Leigh Martin creates paintings from raster scanning and printing techniques.

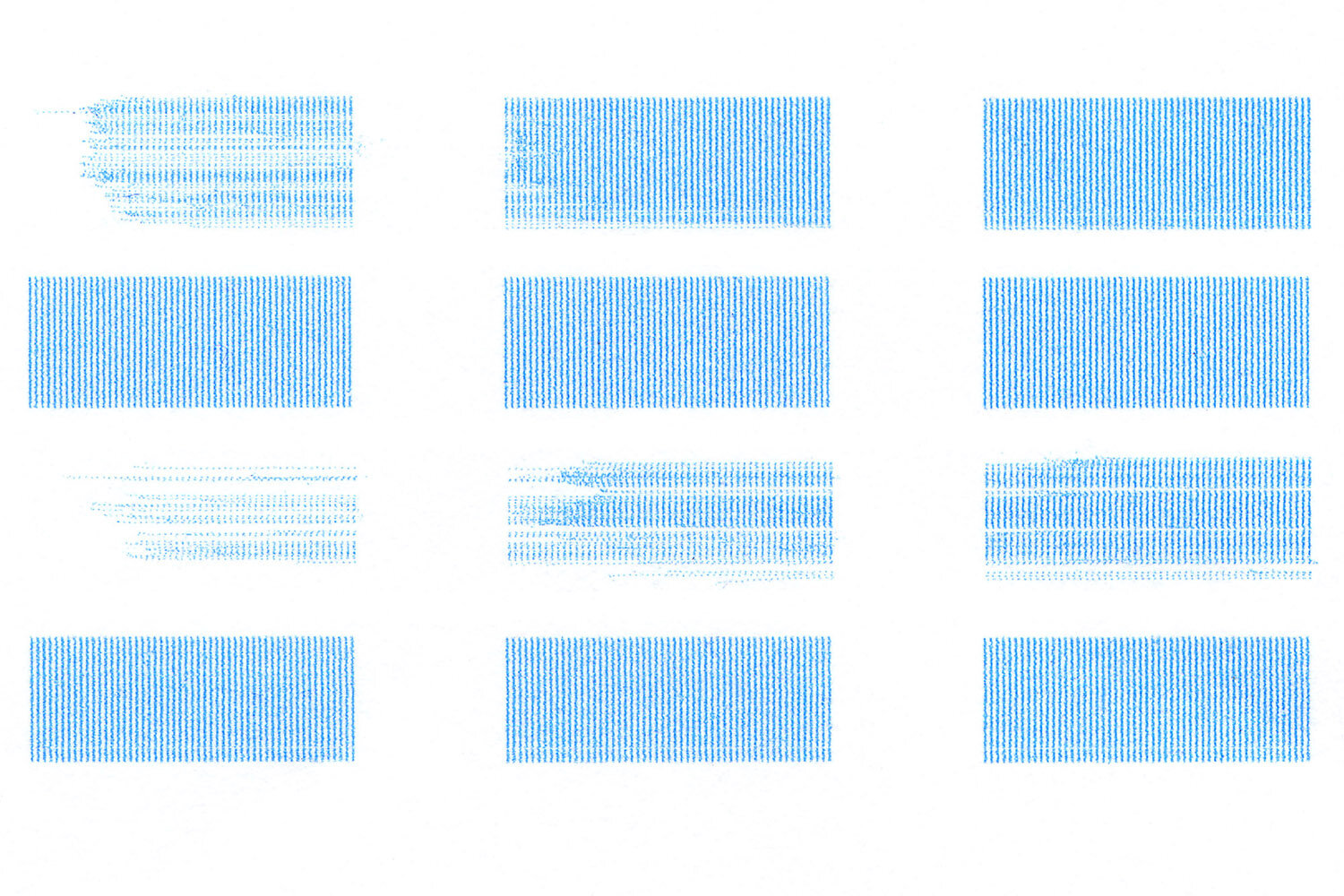

Brian Eno once said something to the effect that the future avant-garde would emerge from the glitches in modern technological production. “My own feeling” Sontier says, “is that the glitches are more an inherent part of a system. That is, you don’t approach a technology as a system that operates perfectly most of the time, with failings that need to be fixed occasionally. You treat it, as all systems, as human creations with inherent problems and inconsistencies that can always be improved on, but maybe at times, can create breakdowns that are more interesting than the original intent. I suspect Eno would go along with that, and that his Oblique Strategies are a tool to expose the humanness of systems that we labour under.”

“There’s an argument, he says, “that technology has created such forward momentum that reflection on technology that has already passed is necessary to fully assimilate its effects. The glitch and the notion of error and the reinterpretation of the outdated are ways we might reassess their usefulness or significance (or dominance and constraints). The pace of change and the involved commerciality that is keen to hide its significance also means that looking back from the future becomes inevitable.”

This approach offers a counterpoint to Heidegger’s The Question Concerning Technology (1954) where a distinction is drawn between techné (technique, art, the organic facilitation of the emergence of truth from nature) and technology (the human-centric extraction of information from nature by brute force). Is it not possible to use technology in a way that satisfies Heidegger’s prerequisites for techné?

Indeed, perhaps we should look to Bruno Latour’s notion of iconoclash when there is an ambiguous uncertainty about what is actually happening when an image or concept is destroyed, perhaps in an act that is actually a form of creation itself beyond merely ironically deconstructing established forms and norms. The glitch is not necessarily a failure to function or transmit, but a synergy that is part of a holistic creative gestalt – creation and destruction coexisting in superimposition. Ambiguity, uncertainty and happenstance are necessary for that primal creative soup that exists in continuity with the history of technology and human-originated systems of knowledge.

“One of my interests,” says Sontier, “is looking at similarities and differences that digital processes can bring to the medium. Light sensitivity, one defining notion of photography, has moved from silver and other chemical based compounds, to light sensitive electronic sensors. Light sensitive papers, for output, have become coated papers that take up inks or dyes. So in some respects nothing has changed, or perhaps digital photography is part of the same evolution (rather than a revolution) that say Kodak and other companies brought at various points to photography –“You Press the Button, We Do the Rest”, and the Kodachrome slide for instance. I think we are still struggling to determine what technology is offering and taking away. A lot of the digital, post-internet and glitch art that I have seen seems to still be addressing very old problems in a naïve way or wedded to a glorification of technical competency.

There are a few though, who I think have taken technology to task on their own terms – Laurie Anderson seemed to do this starting with her use of tape-head violin bows to the 90’s stage shows, and Trevor Paglen in his recent visual-geographical investigations of surveillance and AI. Maybe a direct example of Eno’s idea is Symphony #1 for Dot Matrix Printers by [The User]. Although basically a musique concrete field recording, it’s a great example of looking back at ‘new’ technology with a wary eye and producing compelling sound. Although I have a technical background, I’m deeply suspicious of where technology is taking us, or more accurately, where we are allowing ourselves to be taken by our unaware embracing of the systems that build up around it.”

These are ancient roots indeed, extending back through the esoteric schools of philosophy, Neoplatonism and Gnosticism, even unto the ancient mystery cults of Dionysus and Eleusis, even the art of prophecy by reading the random. Knowledge in its raw state is a dangerous thing and tends to accumulate systems and riddles by which it is mediated to an uninitiated audience. Art offers an opportunity to re-enchant technology with the random, the magical and the possible.

Photography, in all of its pre- and post-digital manifestations, is uniquely positioned within technology to do that, probably because it embodies that transitional lineage between the analogue and digital, documentary and virtual. “Photography” is inclusive, expansive, cumulative, and elastic, growing to accommodate, facilitate and assimilate, especially when it comes to technological and social change.

“My interest,” says Sontier, “is in the uncertainties in our current knowledge and in past theories that have been rejected, as well as new theories that have varying levels of credibility. Rather than a quest with a particular outcome, it is apparent that we will continue to live with unanswered questions. My work's approach is with a feeling of revelry in this uncertainty, but it also asks how we might use knowledge and uncertainty to position and move forward. “

Sontier sees a symbiotic relation between science, photography and technology. “The bounds on photography have expanded several times over the last number of decades,” he says, “perhaps continually since its multifarious births in the form of several different processes. Photography, unlike most other arts is built on and embedded in discovery and technology. I’d argue that photography continually expands to fit the technically possible. So, digital materials and processes, as they are explored, gradually add to what photography can be.”

Sontier is part of this expanded field of technology full of conceptual possibility, capable of connecting to the physical and social world in an incredible diversity of novel ways, while always remaining essentially its own entity where past and future meet.

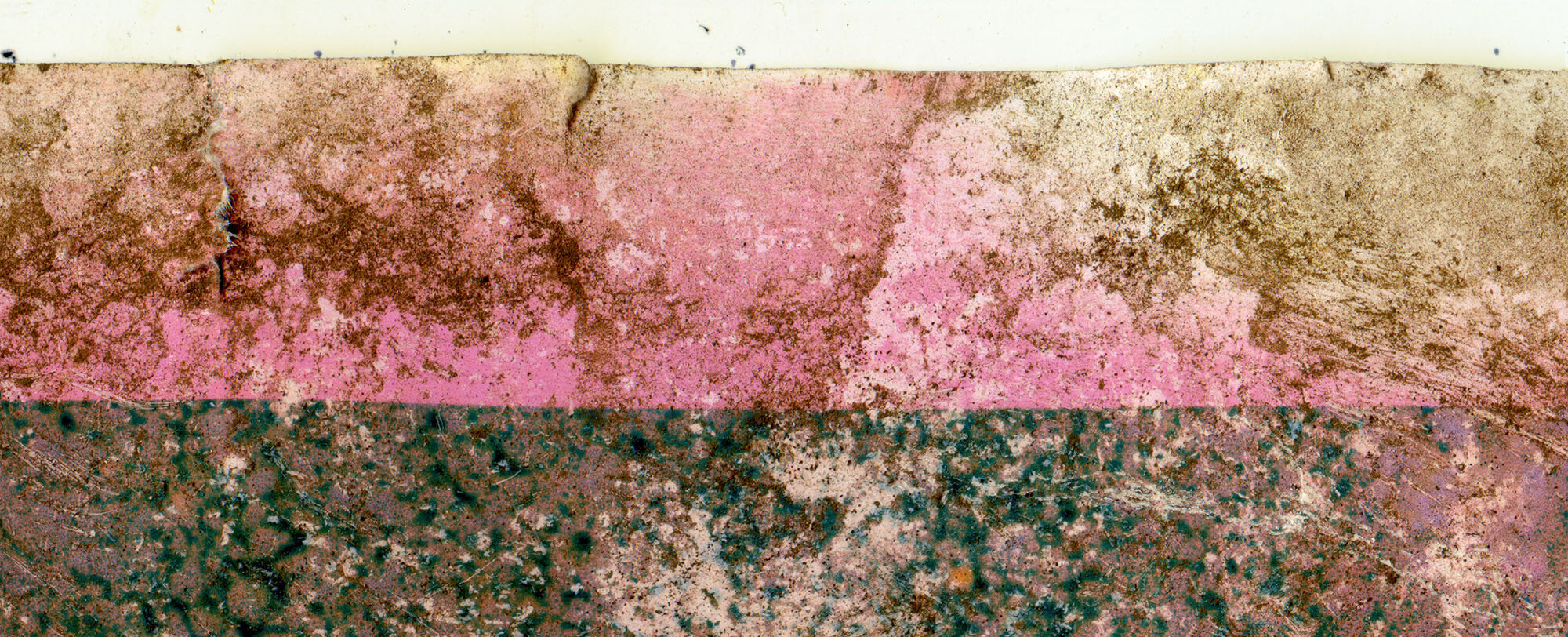

“The camera, the printer, the scanner, the inks and the papers become open to investigation,” he says, “in the same way that say, Marco Breuer and Alison Rossiter explore silver gelatin papers, or Matthew Brandt has applied lake water to, or buried prints in the environment the image came from. My work with digital processes isn’t done as antagonistic to what others are doing in an analogue way – I’m fascinated by those explorations too, but I think, why only look backward – the new materials of photography hold an untapped beauty of their own, with a requirement to look carefully at where we are going.”

Andrew Paul Wood is a Christchurch-based independent cultural historian, art writer and critic. He writes for a number of publications including Art News New Zealand and Art Monthly Australasia. He was co-translator (with Friedrich Voit) of two collections of the poetry of Karl Wolfskehl, and is art and essays editor at takahē magazine.

Born in England, Stu Sontier has lived in New Zealand since the age of 8.

As a photographer he previously worked with traditional silver gelatin printing in an extended documentary tradition and was an active committee member of PhotoForum for many years. After a break which included raising a child and reassessing the personal importance of photography, he now works in a more conceptual way where traditional photographic 'rules' are malleable and open to exploration.

instagram: https://www.instagram.com/stusontierphoto/