Everywhere We Look - curated exhibition

Everywhere We Look

Holly Best, Joyce Campbell, Tash Hopkins, Téhlor-Lina Mareko, Johanna Mechen, Anne Noble, Jasmine Togo-Brisby, Kate van der Drift, Mia Vinaccia and Virginia Woods-Jack

Online exhibition curated by Women in Photography NZ & AU for PhotoForum, October 2019

Virginia Woods-Jack, All the Stars

At the 2016 Toronto International Film Festival, director Jill Soloway gave a masterclass titled ‘The Female Gaze’(1). In the lecture, they define three ways that the female and non-binary gaze might present itself: the gazed gaze, which conveys how it feels to be the object of the male gaze; returning the gaze, an acknowledgment that women see men, seeing them; and feeling seeing, a way of feeling, rather than looking at, objects.

Significantly, the female gaze is not a direct reversal of the male gaze - an idea first articulated by Laura Mulvey in 1975. The female and non-binary gaze is about being and bearing witness to collective and personal events. Soloway explains:

The female gaze is more than a camera or a shooting style, it is that empathy generator that says: I was there in that room. The female gaze says I was there, and this is my shame, and this is my life, this is my humor, I’ll take all of it and put it into my protagonist, with music, with light, and we will all side with HER.(2)

Though Soloway’s ideas are based around their experiences of the film industry, they resonated strongly with photographers Christine McFetridge, Caroline McQuarrie and Virginia Woods-Jack, who work together as the facilitators of Women in Photography NZ & AU (WIP). WIP, started in 2018 to address gender inequity in the arts, promotes female and non-binary photographers based in New Zealand and Australia. Everywhere We Look is the platform’s first exhibition.

In this online exhibition, WIP aim to use Soloway’s lecture as a point of departure; aligning a selection of artists to each of their three elements of the female and non-binary gaze to interpret them within the context of Aotearoa New Zealand. By no means a survey show, the artists included interpret their experiences of the world and often draw parallels between the effects of patriarchy and the effects of colonisation in our country. If feminism is about ‘how we pick each other up’(3), then the photographs in Everywhere We Look offer insight about how we might do this; together.

The Gazed Gaze

Soloway’s idea of the ‘gazed gaze’ has the most direct inverse relationship to the male gaze. It’s an exploration of how it feels to be seen; to be the object of the gaze. Tash Hopkins most often turns her camera on adolescents and young adults. Her participants are young people on the cusp of their adult lives trying on identities to find out which tribe they fit into. The series Western Springs centres on a high school, where Hopkins photographs teenagers in an attempt to counter the one-dimensional view often given by mainstream media. She states: “I wanted to counter those generalisations by making images that give a glimpse into aspects of their interior lives.(4)”

This generation, so used to being photographed, is unfamiliar with her large format camera. By working slowly and with an awareness of the experience of the participants, Hopkins’ methods align to Soloway’s ideas of using a bodily awareness in the making of the imagery. They claim their space and they know we’re watching them; but they’re at home and we’re being invited in.

A different kind of invitation is being offered in Virginia Woods-Jack’s ongoing series Even as you watch I am fleeting. In recording life with her two teenage daughters, the work is as much about her as it is about them. Woods-Jack explains: “I now see how much I am actually in these images, revisiting this teenage period in my own life." As such, the series is a way of making sense of the uncertainty inherent to adolescent experience; both the memory of her own and the experiences she sees playing out in her daughters' lives.

Again, there is an embodiment to this work. It feels both embedded in a life and outside of it. It is everyday moments, but those moments are made special by being photographed, by being seen. The work seems to have been made in moments of leisure, which is traditionally when we take photos of our family. However, in the depiction of moments of doubt, discovery and wonder, these images eschew the constructed happy family photo-norm.

Mia Vinaccia is an emerging photographer, barely older than the young people pictured by Hopkins and Woods-Jack, who turns the camera on herself. Coz u a gem (from the photobook of the same name) shows a young woman using photography to work out who she is, while claiming space to do so. Vinaccia’s work boldly proclaims that you don’t need to wait until you have everything figured out – you can go and live your life.

That said, there is an undercurrent of vulnerability in the work. Vinaccia acknowledges the negative effect the male gaze has on young women: “We are constantly bombarded with images of beauty, Cos u a gem is a way of countering these problematic images that work to knock us down.(5)” This work shows both an acute awareness of being looked at and a willingness to engage with the effects that being looked at has. If, as Soloway explains, the female gaze inspires a collective roar, then Vinaccia’s Coz u a gem is at the crux of this call.

Returning the Gaze

This aspect of Soloway’s female gaze, they suggest, is the one we currently see the least of. It requires an understanding of cultural history; that if we don’t write it, we are written by it. Soloway states: “This part of the female gaze is a socio-political justice-demanding way of art making… Protagonism is propaganda that protects and perpetuates privilege.”(6) Which means that in moving image whoever writes the protagonist, has the privilege.

In still photography the ‘protagonist’ is more nuanced than in moving image, and Anne Noble’s Bitch in Slippers is an example of this. Depicting heavy machinery at Antarctica New Zealand’s McMurdo Station, this series of images at first seems innocuous. Then we notice that all the machines have been named, like WWII airplanes, with women’s names. Stemming from a military history, the machinery bears names such as ‘Hot Lips’ ‘Hazel’ and ‘Misty’, painted with varying degrees of skill. The practice was apparently halted for a time after a crane was named ‘Bitch in Slippers’. It has since re-emerged.

Despite not including a single photograph of a female person, this work is about objectification at its most absurd. Laugh it off, the perpetrators might say, it’s just a joke: boys will be boys. But Noble makes portraits of the now personified machinery, she gives them dignity. Her gaze is turned back towards the men who painted these names, and, by claiming her subjectivity, they now become the object of her gaze.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, gender identity isn’t the only privilege that has been perpetuated through mainstream culture. For many photographers, claiming a space for themselves means confronting more than one injustice. Both Jasmine Togo-Brisby and Tehlor-Lina Mareko turn the tables on the colonial forces that have heavily impacted their lives and those of their ancestors.

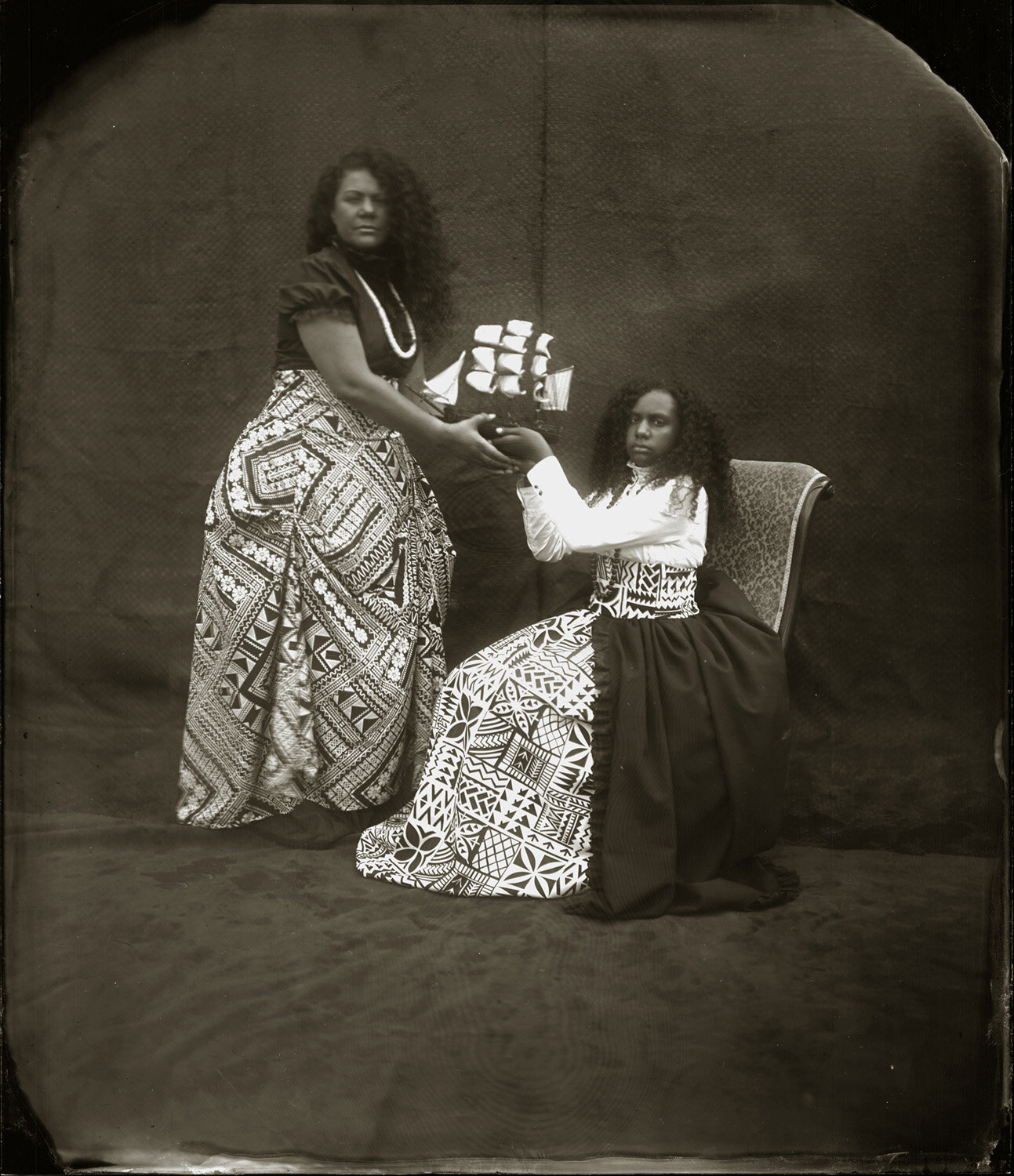

Jasmine Togo-Brisby’s work considers this history in a very direct way. Wellington-based Togo-Brisby is a South Sea Islander, a term given to Australian-born descendents of the South Seas slave trade. Traditionally a tool of the coloniser, Togo-Brisby writes of how photography was used by the Australian government as a means of control:

The Australian institutions almost always own our images. Commonly unknown subjects in photographs taken by unknown photographers, therefore deemed property of the State… As Australian Pacific Slave diaspora these images are part of our visual culture, the archives [are] part of our cultural practice. Our collections range from odd performance to painful realities.(7)

Togo-Brisby’s photographs utilise a tool of oppression, wet-plate collodion photographs on tin, to make her own record of her family history. Photographing herself, her mother and her daughter, Togo-Brisby claims her maternal line as a source of strength, while acknowledging the intergenerational trauma caused. By placing their colonised experience at the centre of her work, Togo-Brisby turns the gaze back onto those who persecuted her family and those who would claim to colonise them still.

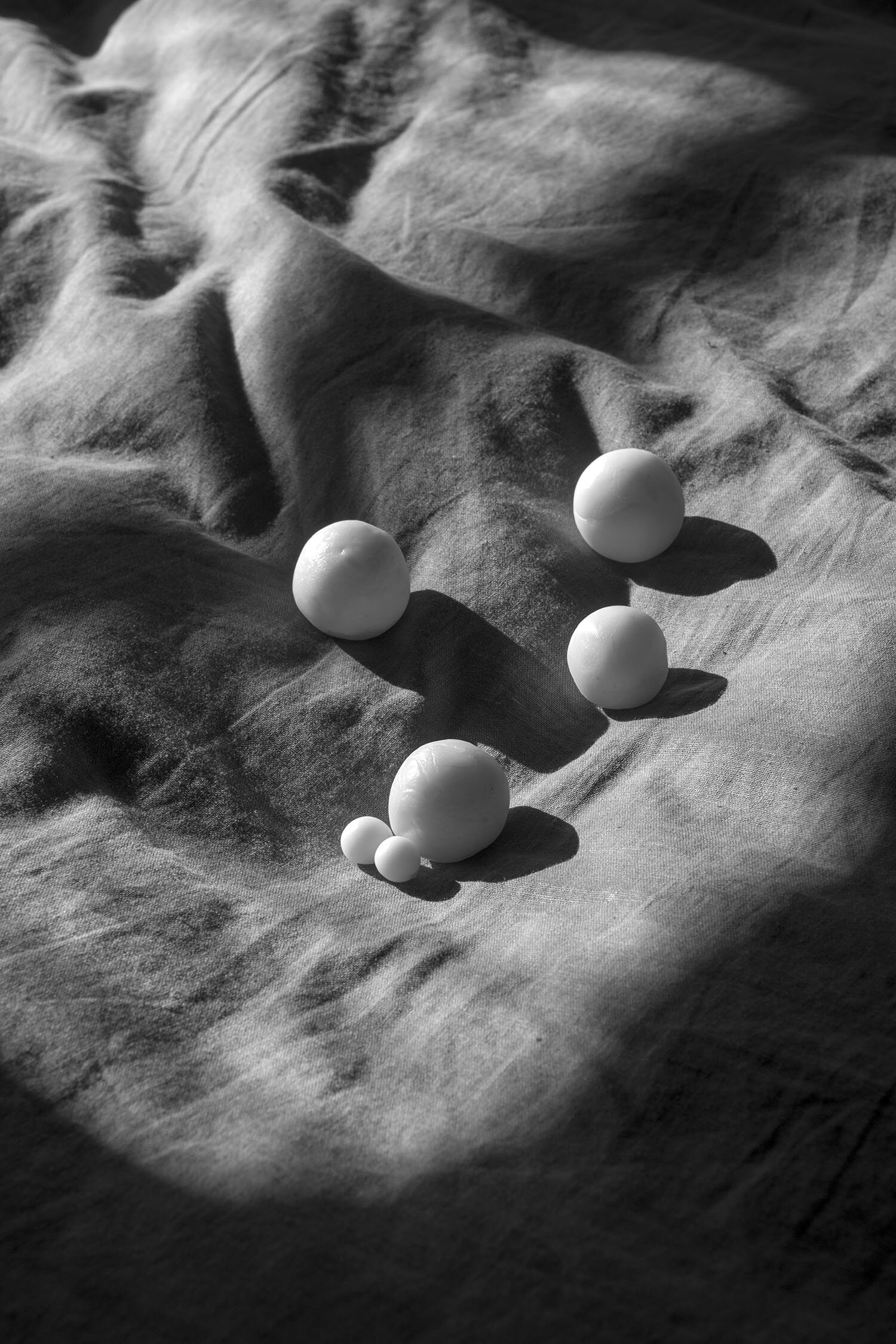

Téhlor-Lina Mareko is a New Zealand-born artist of Samoan heritage who is also claiming her right to turn the colonial gaze back on itself. Mareko’s work ‘Toto Masa’a’ depicts the traditional Samoan story Sina and the Eel, which tells of the first coconut tree planting. A pre-colonial story, it has endured through oral storytelling despite the prevalence of Christianity in Samoa. Mareko says: “Sina and the Eel, although simple, is an intricate story with a variety of messages. The more I explored and delved into photographing the story, the more I became aware of the complexities of the messages and morals woven into this simple story which are still relevant to today's world and the Samoan way of life.”(8) The first of which Mareko lists is a woman’s right to say ‘no’.

Aware of the intricacies of the gaze and how it is implicated in colonialism, Mareko wanted to do more than simply critique the past: “I intended to provide a language of Native power and latitude in preference to simply a restricted critique of colonial authority.”(9) In this series, Mareko becomes the protagonist with blood on her hands as she holds the body of the eel and the coconut which results from its death. Staring directly into the camera she confronts us and our complicity in perpetuating stories which put young women in impossible situations.

Feeling Seeing

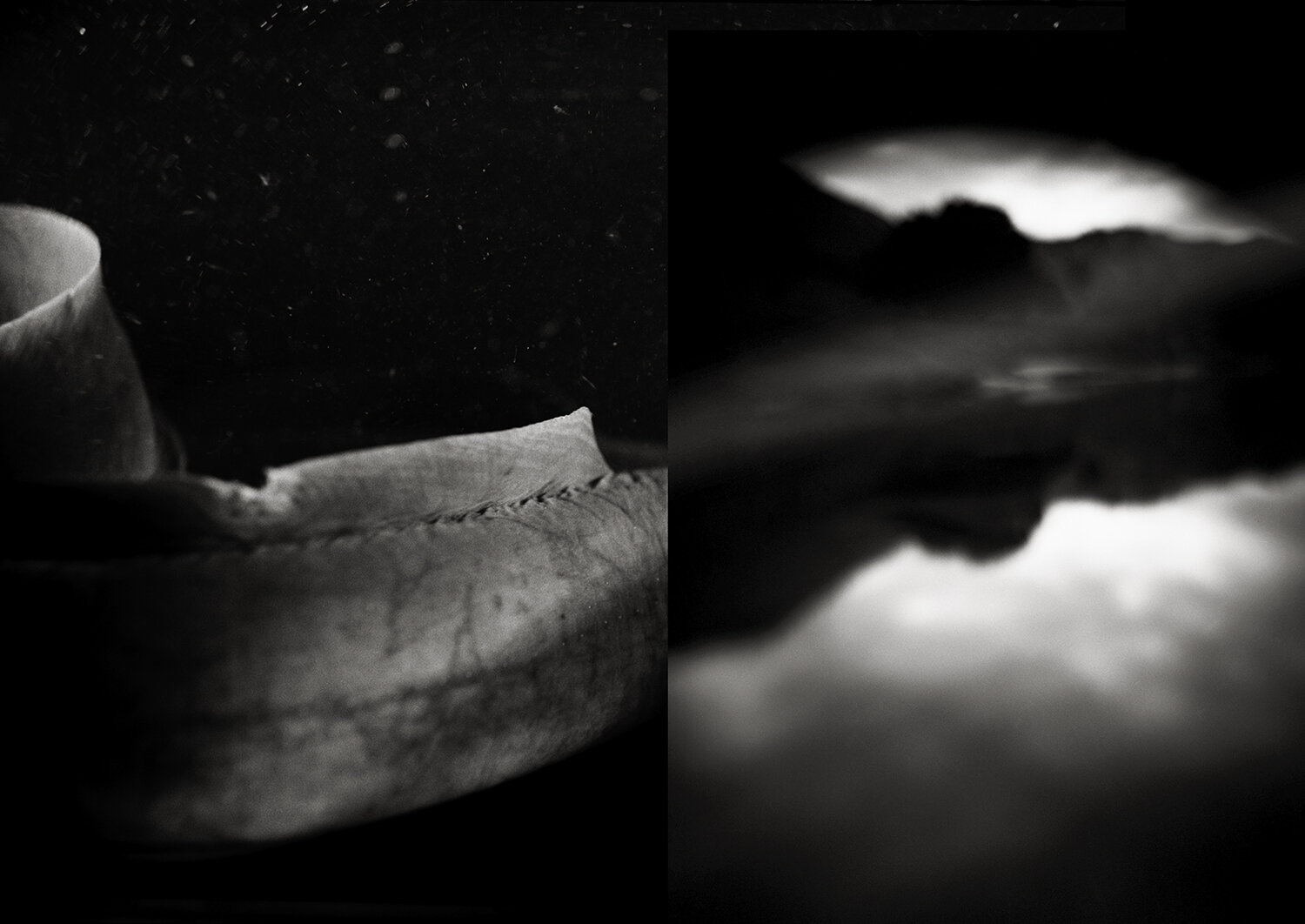

‘Feeling seeing’ is not about what is photographed, but how. It’s about how the photographer makes their work. One way to counter the trope of the singular artistic (male) genius is to make work collaboratively. Johanna Mechen and Joyce Campbell are two practitioners who do just that. Mechen’s work Sonorous Shadow is a series of still photographs and moving image works made in collaboration with her two children. While artist-in-residence at Toi Pōneke in Wellington, Mechen mined an archive of photographs taken while her children were young. Consulting with them, they selected particular moments to recreate and photographs properly, with the luxury of time. This practice suggests both a curation and an ability to edit the memories in hindsight (including the use of post-production to get the images just right), but it also means tackling issues around consent when incorporating images of the photographer’s / artist’s children. Here the pre-teen and early teen children have the right to say no, have their own creative input, and approval of the final work. The resulting sumptuous black and white photographs are carefully observed studies of light and shadow that illuminate everyday objects.

Joyce Campbell’s series Te Taniwha is a collaboration of another kind. Returning to the valley she grew up in, she explores local Māori mythology and ecology. Shooting large and medium format black and white film, her ominous imagery hints at histories beyond facts. Campbell states: “I am attempting to theorize and visualize an ecology that is ... limited, damaged, injured and defiled, or resistant, volitional and responding with fury. To further my research goals, I have found myself turning to the sacred, the visionary and the mythological, and to primal images and experiences of the maternal body becoming animal.” (10) Channeling somatic experience into a visual medium is how Soloway defines ‘feeling seeing’.

Kate van der Drift’s series Water Slows As It Rounds the Bend also engages with place and landscape, but from a Pākeha point of view. Van der Drift is not afraid to make beautiful pictures, which could be considered a risky strategy in the art world post-1990s German ‘objectivity’. However while utilising some traditional landscape tropes, she eschews others, preferring to photograph in portrait format. This simple but effective disruption of the recognised format of landscape photography gives us foreground and sky but very little peripheral information. The images remind us of the colonial and industrial toll people have had and continue to have on the environment; what we see is shaped by human hand and introduced flora and fauna (some now considered dangerous weeds). Here, van der Drift quietly points out that pretty pictures have complex undertones.

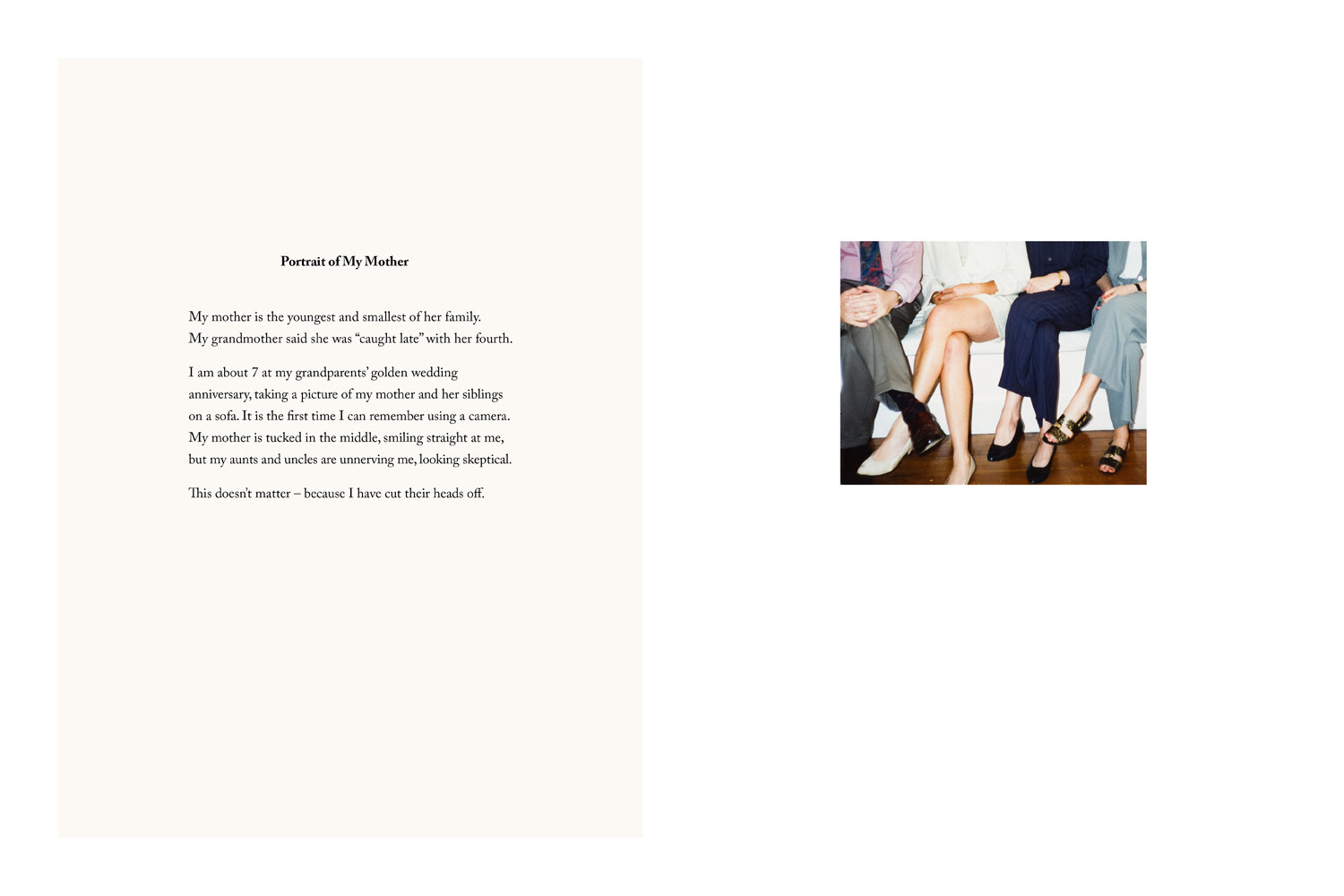

Holly Best also confronts photographic conventions in her work A Series of Disappointments. These are her ‘failed’ photographs, the ones that didn’t make the cut but have stayed with her – the ones that got away. Blurry, dark and unsuccessfully framed, this work challenges what makes a ‘good’ photograph. It also engages with photography as a cipher for memory, and in a similar way to Mechen’s work calls out its shortcomings in this regard. It is Best’s combination of text and image that proves so poignant, both the feeling for what might have been, and the joy and humour in what actually is. These images have their own successes, despite their failings. The work is strong for its vulnerability. Not so long ago (and perhaps even still), women had to be twice as good as men to succeed. Being able to celebrate supposed failure shows a maturity in the position of women in the photographic world.

All three aspects of Soloway’s female gaze are thriving in photography in Aotearoa New Zealand, and we could have selected many more practitioners for each category. Photographers here are critically challenging how the camera has been historically used and turning it into a tool for subversion; showing intelligence, strength and a common sense of purpose.

Women in Photography NZ & AU, October , 2019

[1] Jill Soloway, Jill Soloway on The Female Gaze, Toronto International Film Festival 2016, accessed 22 January 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pnBvppooD9I.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life (Duke University Press: London, 2017), p. 1.

[4] Text provided by Hopkins to the curators.

[5] Text from self-published photobook ‘Coz u a gem’ by Mia Vinaccia.

[6] Soloway.

[7] Jasmine Togo-Brisby, ‘Adrift’, 2019.

[8] Text provided by Mareko to the curators.

[9] Ibid.

Christine McFetridge is a photographer and writer represented by M.33, Melbourne. She is currently an MFA by Research candidate at RMIT University and a founding member of Women in Photography NZ & AU.

Caroline McQuarrie is a Lecturer in Photography in Whiti o Rehua School of Art, Massey University, Wellington, and a founding member of Women in Photography NZ & AU. She creates photographic and textile-based exhibitions which explore home, histories and land use.

Virginia Woods-Jack is an artist based in Wellington and the founder of Women in Photography NZ & AU. She uses photography to explore human experience and attachments to time, place and the natural world from a female perspective.