'Ground Water Mirror' - An interview with Conor Clarke, 2018

Ground Water Mirror

An interview with Conor Clarke

Emil McAvoy for PhotoForum

February 2018

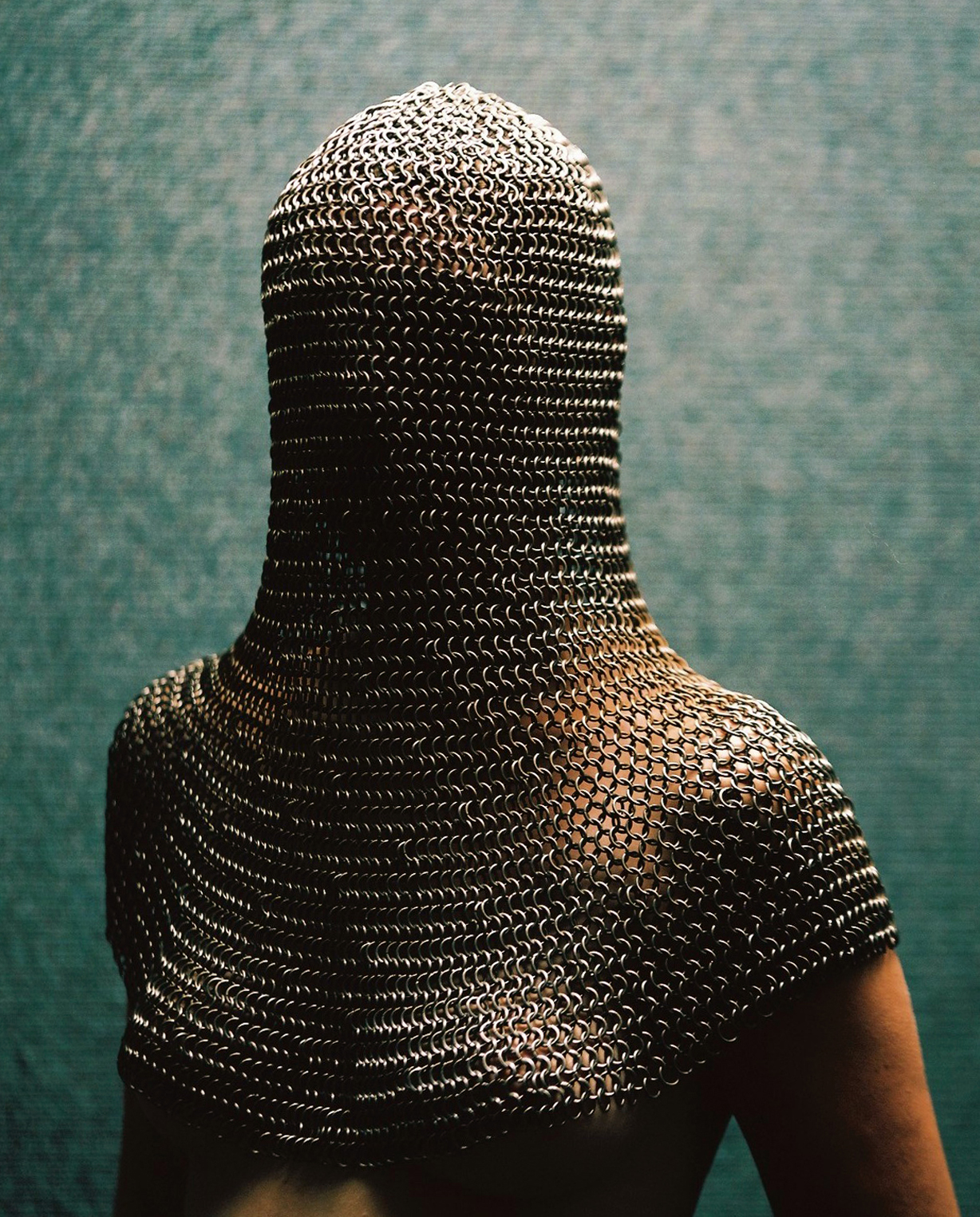

Conor Clarke. Untitled (veil of the soul), 2018

New Zealand born, Berlin based photographer Conor Clarke was back in Auckland for a fleeting visit in February-March when we caught up. Clarke returned to Aotearoa to take up a residency at Tylee Cottage in Whanganui late last year. She is currently preparing her forthcoming post-residency exhibition Ground Water Mirror at the Sarjeant Gallery, scheduled for December.

She is also re-presenting her Berlin landscape project Scenic Potential alongside works by artist Tia Huia Ranginui at the Franklin Art Centre, Pukekohe, March 3 - April 7. Their exhibition Sorry, not sorry emerged from the two meeting in Whanganui while Clarke was the artist in residence. In addition, she is developing a solo show at Two Rooms later this year as part of the Auckland Festival of Photography.

Conor, thanks for sharing some of your thoughts with PhotoForum. You’ve been based in Berlin for some years now. How does it feel to return to New Zealand this time around? What are the things you enjoy most here given the geographical distance and cultural differences?

It’s always great coming home to visit friends and family, but it’s really hard to focus on making work when I’m surfing couches, borrowing cars and generally reliant on other people’s generosity all the time. Living in Europe has also made me realise how much New Zealanders depend on and fetishise their cars, maybe it’s a lack a decent public transport that’s the problem, but it’s motivated me not to use one at all on this trip, or at least, only when absolutely necessary. I get most of my ideas on foot anyway, and it’s easier to trespass without a number plate.

Berlin has long been romanticised as an artistic centre – and for good reason – but how do you find the realities of living and working there? What are the highs and lows for you?

During my studies at Elam we always talked about going to Berlin, but it turns out I knew very little about it. There’s way more open, green public space than I’d imagined, and so much water – canals, rivers, lakes, the infrastructure network and a super high water table. This has been the inspiration for my new project Ground Water Mirror, a slightly incorrect and literal translation of Grundwasserspiegel, the German word for water table.

In terms of living and working there, lack of paid work for the growing population of creative young people and rising rents make it more difficult. The opportunity to live in the middle of Europe though and the range of art and cultural events on offer make it so worth it…I do get a bit overwhelmed by the social aspect though, it’s easy to get distracted.

Your recent residency project at Tylee Cottage was focused on the Whanganui river. The residency has also featured a number of photographers in its history. What is your personal take on this river and its photographic representation?

The river is an important part of the project, but I’m interested in fresh water in general, in all the waters that flow throughout daily life. I make no traditional views looking down on the river from a high viewpoint, I photograph the river from the river, or the ground from eye level, usually isolating subjects at close range. Any sweeping vistas I have made in the past have critiqued that quintessential, possessive view of land, water and people. I also want to challenge the categories that we put water into, like “resource”, or “nature destination”, and use these categories to talk about the connectedness of water, of nature. I am a romantic, but it’s more romanticism as a subtle form of activism.

What can visitors expect from your exhibition Ground Water Mirror at the Sarjeant?

There will be two parts: a series of photographic works at the Sarjeant gallery, and a sound work which I hope to be somewhere offsite. The photographs touch on lots of things: surveying, measurement of land and water quality, the New Zealand Company, nature categories, perception and representation of nature, the reflective qualities of water, early paddle steamers and industry on the river. Recurring subjects include chains, water, mountains, and people. The people part is a first for me in a really long time.

The second work is a collection of sound recordings from various sites and water sources connected to Whanganui that generally fall into the infrastructure or resource categories, like storm water drains, the town water supply, a dam, decorative water features, leaky guttering, Tongariro power scheme intakes, etc. I’m creating a collective image of nature using sound.

In a recent interview with RNZ [from 18'45"] you spoke of an interest in fresh water as a metaphor for nature, and emblematic of a human longing to connect with it. Nature as a concept, a destination, a resource, particularly in relation to human infrastructure. As you’ll be aware, the issue of water ownership and its sale to commercial bottlers for export has been foregrounded in recent New Zealand politics and media coverage. Interconnected to this national issue is the granting of the legal rights of personhood to the Whanganui river – thought to be the first in the world – and the associated Māori cosmologies which inform this. Would you care to speak to any of these aspects further?

Nature as we know it is becoming a resource. A tick on a bucket list, a solution to urban living. The Tongariro crossing is a good example of this, a fragile eco system, a gift to the public that actually wasn’t. Mount Tongariro (along with Ruapehu) is the source of the Whanganui river.

There is an old Māori tradition of shielding the eyes with woven harakeke or karaka leaves when walking near the central plateau so as not to be tempted to look up at those extremely tapu living mountain ancestors. Like all traditions, it comes with a practical reason too, protecting the eyes from the sun, snow glare and windblown sand.

Thinking about the tradition today, it feels once again relevant, even necessary. That by seeing less, taking less, thinking or feeling more…we could experience the world with more clarity than standing in a single file queue with hundreds, sometimes thousands of people waiting to “do” the crossing. I recently talked to some blind and partially sighted people about their experiences in such special places, and found their verbal descriptions carried a far greater depth of experience and awareness than my own sighted one.

My problematic relationship with sight has been summarised before by Edgar Allen Poe as seeing through the “the veil of the soul”, or the history of landscape representation. He suggests that we can “at any time double the true beauty of an actual landscape by half closing our eyes as we look at it”, that “the naked senses sometimes see too little – but then again, they always see too much”.i

Your 2015 residency at Waitawa Regional Park outside Auckland responded to the landscape, its history and communities, along with your personal family connection to the land. What were the most significant ‘take aways’ for you?

I found out that isolation is incredibly productive! And I rediscovered gorse, one of my favorite flowering shrubs.

What are you most interested in at the moment? Are there particular currents in contemporary photography – ideas, discussions, artists or scenes – that inspire you at present?

To be honest, I’ve been in a bit of a bubble since being here in New Zealand and haven’t paid much attention to the international art world, partly due to the death of my laptop soon after my arrival. It’s been really refreshing and productive being more or less computer-free!

I do feel like the subjects I make work about aren’t uncommon though, like urban nature. It’s a zeitgeist thing, responding to the state of the environment: the problems and solutions that come with urban living, how land is represented throughout art history and therefore perceived, and responding to the similarities and differences between life in Germany and New Zealand over the past eight and a half years.

You can see more of Conor's work at conorvonclarks.com

A video about Conor's Waitawa Regional Park residency can be viewed here.

i Edgar Allan Poe, "The Veil of the Soul," in The Unknown Poe: An Anthology of Fugitive Writings, ed. Raymond Foye (San Francisco, California: City Lights Books, 1980), 51.