Ways of Being - reviewed

Ways of Being: Representation and Photography from the Dowse Collection

Glenn Jowitt, Rebecca Swan, Ngahuia Harrison, Mark Adams, Andrew Ross, Bruce Connew

Dowse Art Museum

08 December 2018 - 28 April 2019

Reviewed by Deidra Sullivan for PhotoForum, February 2019

Who’s afraid of social documentary?

Bruce Connew, Jimmy ‘Grub’ Duggan & Brucie Brown, east heading haulage, Strongman Mine, 9 Mile, Westland, New Zealand, 1986.

Featuring the work of six New Zealand documentary photographers from the Dowse collection, Ways of Being: Representation and Photography from the Dowse Collection, seeks to investigate the evolution of documentary practice since the early 1980s.

The exhibition title is a play on John Berger’s seminal text Ways of Seeing, which, since its publication in 1972, has changed our cultural understanding of art and photography. Berger’s analysis rejected established art history with its emphasis on aesthetics and connoisseurship, instead emphasising the ways in which the meaning of visual culture is constructed by personal and cultural assumptions about “beauty, truth, genius, civilisation, form, status, taste.”[1] Ways of Seeing also drew on Walter Benjamin’s The work of art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction to explore how photographic reproduction shifted the value of original artworks, and Berger extended this critique to consider how photography operates as a visual language within a capitalist system to sell ideas (for example, about gendered stereotypes, wealth, status) through products.

This questioning of the supposed neutrality of ideas of genius, taste, aesthetics and truth also manifested itself in critiques of documentary photography during the 1980s. Martha Rosler’s In, around and afterthoughts (on documentary photography)[2] gave traditional documentary photography a run for its money by reconsidering the relationships between the photographer and subject, between the documentary photograph and its connection with ‘truth’. Rosler argued, “The exposé, the compassion and outrage of documentary fuelled by the dedication to reform has shaded over onto combinations of exoticism, tourism, voyeurism, psychologism and metaphysics, trophy hunting and careerism. ”Documentary testifies finally”, she suggested, “to the bravery or (dare we name it?), the manipulativeness and savvy of the photographer, who entered a situation of physical danger, social restrictedness, human decay, or combinations of these, and saved us the trouble.” Chastening words indeed for any documentary photographer.

These concerns about the ethics of representation have shaped documentary photography since, and they are the intended heart of Ways of Being. The exhibition literature notes, “Until the late twentieth century, photographers who worked in [documentary photography] aimed to capture life as it was, operating with the intention to intervene as little as possible. However, since this time, people have deliberated on issues of human rights and power dynamics at play in photography, questioning the role of the photographer.” Photographers have also responded to criticisms that documentary is too often ‘weaponised’ against its human subjects, ‘othering’ them and reducing them to symbols rather than acknowledging them as individuals. To avoid this, most contemporary documentary photographers ensure their subjects are fully aware of and active in the process of image production.

In order to fully examine this evolution in documentary, Ways of Being would benefit from further context, by way of publications, public programme events or supplementary materials, to further unpack the historical and critical background against which the selected work sits. It would also benefit from a broader selection of work, potentially supplemented by works from outside the Dowse collection. The three photographers in this show practicing within a traditional social documentary framework who might potentially be subject to a Rosler-esque critique – Glenn Jowitt, Andrew Ross, and Bruce Connew – demonstrate in their work an evident sensitivity toward their subjects.

Glenn Jowitt, Installation View. Photo, Elias Rodriguez.

Jowitt’s photographs of Pasifika culture emerged through a sustained connection with the Pasifika community, his stated intention being to use his camera in “a gentle way” to represent his subjects compassionately. The relatively small selection of his work on display (eleven prints) show a variety of subjects and locations that are testimony to his commitment to building relationships of trust with his subjects over time.

Andrew Ross, The Swensson’s front room, 45 Holloway Road, Mitchelltown, (2008).

Similarly, Andrew Ross’s magnificent photograph The Swensson’s front room, 45 Holloway Road, Mitchelltown, (2008), is the result of a long term connection with the family. “I knew the Swenssons for ten years before I was allowed to photograph their home,” Ross commented – an investment in time and friendship that manifests in the rich detail of this photograph. Bruce Connew’s photographs of coal miners in Beyond the Pale, (1986), are the result of five months spent with coal miners in seventeen different mines. His photographs convey both a sense of the oppressive nature of the work, and the camaraderie of the miners. We might observe that Connew’s work did indeed ‘save us the trouble’ of venturing into situations of ‘physical danger,’ but quite frankly, given he was willing to spend five months down a mine, I’m reluctant to suggest a motivation of careerism or trophy hunting. This is the power of a documentary practice that is created with connection and integrity: it conveys visual narratives and descriptive information that viewers would not otherwise be party to; it extends our understanding.

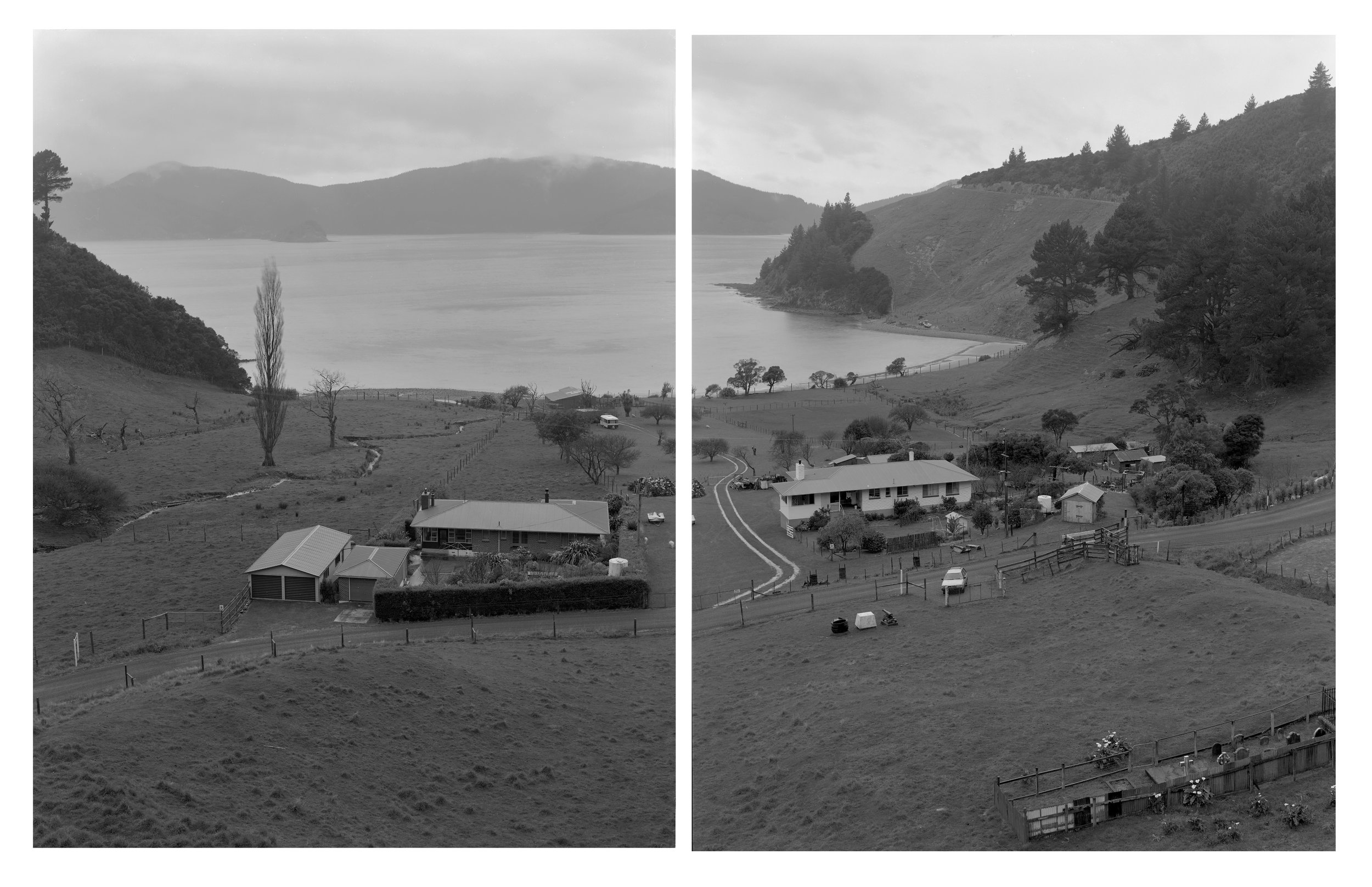

Mark Adams, Hora Hora Kakahu Kakapo Bay - Guards Bay 1, 2012.

Rosler’s critique of documentary prompted a shift in documentary practice – and a caution in engaging with what might be perceived as the didactic qualities of traditional social documentary. The work of Mark Adams, Rebecca Swan and Ngahuia Harrison point to the ways in which documentary strategies have evolved in response to these postmodern concerns. Adam’s landscapes, while largely empty of people, reference the history of the European colonisation of Māori land. Hora Hora Kakahu Kakapo Bay – Guards Bay 1, (2012) depicts an uneventful rural scene: two houses, sheds and cars, edged with hills and a beachfront. The location was one of the six sites where the Treaty of Waitangi was signed in the South Island. Adams’ photographs don’t provide us with a linear narrative or pose a conventional documentary problem to be ‘solved’ – rather, they invite a contemplation of the layered history of the land and its people.

Ngahuia Harrison, installation view. Photo, Elias Rodriguez.

Rebecca Swan and Ngahuia Harrison use portraiture to explore question of gender identity and cultural identity respectively. For her Assume Nothing series Swan worked collaboratively to produce portraits in which her subjects ‘were empowered to present themselves as strong, proud individuals.’ Her three images of Ema are engaging portraits, as are Harrison’s images of her brother, Kahu. Harrison’s work – as with Swan and Adams – also point to ways in which documentary increasingly intersects with other photographic genres – portraiture, still life and landscape are woven throughout the work of these three practitioners. But I can’t help wonder if this work fits more comfortably within – and has more to offer – those genres.

Rebecca Swan, installation view. Photo, Elias Rodriguez.

Ways of Being looks back at documentary practice from a cultural vantage point where we are cautious of any claim to ‘truth.’ We’ve declared all meaning is negotiable, and any potential to achieve certain knowledge through visual representation is highly problematic. In this environment, there’s a risk that the potential of social documentary becomes lost, that photographers self censor, or shy away from topics or questions they feel unable or unqualified to address. Contemporary documentary, instead of asking questions, runs the risk of becoming an exercise in affirmation, a practice no less didactic than conventional social documentary can potentially be. My suggestion therefore, is that while we might value a range of documentary strategies, the work of social documentary practitioners such as Jowitt and Connew remain testament to the value of that approach when it is conducted with compassion and integrity.

Deidra Sullivan teaches photography on the Bachelor of Creativity programme at Te Auaha, WelTec and Whitireia’s joint School of Creativity, Wellington.. She recently co-curated 'Still Looking: Peter McLeavey and the last photograph' at the Adam Art Gallery.

[1] Berger, J. (1972). Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin.

[2] Rosler, M. (1981). In, around and afterthoughts (on documentary photography). In Bolton, R, (ed). The context of meaning: Critical histories of photography. Massachusetts: MIT Press, p.303-325.