Christopher Pryor - featured portfolio

T

Photographs by Chris Pryor

Response by John Dennison for PhotoForum, 08 November 2019

Visible & Invisible: Four Contemplations

Born in Auckland, New Zealand in 1975, Chris Pryor began his adult life studying electronic engineering at the University of Auckland, a course that soon gave way to still photography and film projects. As a cinematographer, Chris filmed a wide variety of documentaries for television and short dramatic films and collaborated on many moving-image art projects before making his directorial debut in How Far is Heaven.

Centring on the life of the Sisters of Compassion at Hiruharama (Jerusalem), on the Whanganui River, How Far is Heaven follows Sister Margaret Mary as she learns to live alongside the local community, including its children, whose humour and unique philosophies transcend the harsher realities of life. Both How Far is Heaven (2012) and the 2015 feature documentary The Ground We Won screened to considerable acclaim in New Zealand and abroad. Chris and partner Miriam Smith were the recipients of the 2017 Harriet Friedlander New York Residency, which afforded Chris the opportunity to rekindle his photography practice.

The photo series T has arisen from trips back to Hiruharama, following this New York sojourn.

Central to Chris’s work is a concern with the way in which a sense of profound connection to the land is made difficult by the impact of colonization, opening up for Pakeha—as largely the beneficiaries of colonization—an ambiguous groundlessness. Another recurrent concern is his fascination with the tensions of late modernity; to adopt philosopher Charles Taylor’s schema, is the ‘frame’ of reality open or closed? [1] Is reality only material, is it more truly spiritual (where reality may be an illusion), or is it the world visible and invisible? With regards to both these concerns, photography has perhaps a useful pertinence, dealing directly and playfully with the ambiguities between the documentary and the acutely personal. It’s a helpfully unstable medium for the question ‘where is here?’

Slide show: Christopher Pryor, Untitled 1-8, from the series T, 2017-2019

Visible & Invisible: Four Contemplations

“For what they were not told, they will see,

and what they have not heard, they will understand”.

Isaiah 52:15

Let us say the problem is one of seeing.

Seeing is more than looking, which is a matter of holding something in one’s regard. It trades in appearances, in cursory impressions. I look at things; I look into things; I look down. I also cultivate a certain look – I become a looking at the world and present a look to the world – it’s intensely self-regarding.

But sight has a reach and scope that calls us beyond ourselves. ‘Now do you see?’, we’re asked—that is, do you intuit beyond the look of things what is also there? And do you not only intuit, but also understand—that is, comprehend and risk agreeing with the reality that now presents itself? To ask me ‘do you see the world is broken?’ is a question of deep understanding that may well require a response entailing nothing less than my whole life.

With seeing, a kind of knowing is in play, a knowing that has to deal with what is the case, visible and invisible, not just the look to things but also the things themselves beyond all looking. Of course, for the inheritors of late modernity and its Romantic reactions, knowing is a word that has long been orphaned, cut off from its necessary relations in epistemology: the body, linguistic, cultural and geographical situatedness, tradition, and so on, not to mention those embarrassing relatives, wisdom and faith; indeed, with this last, it is easier by far to etherealize it as spirituality—that is, a kind of empathy with a larger vibe that you can cultivate sensitivity to in ways that are more or less systematic. In this mindset, any knowing that is ‘spiritual’ is at once elevated as being irreproachably felt and, at the same time (and largely by the same token), dismissed as having no substantial bearing on real life.

The photographic image is dogged by the family dysfunction of Western epistemology, unbelieving about the world visible and invisible, and anxious about how to explain itself. Its mood swings from a ‘documentary’ take on things to intensely self-conscious framings of meaning; and what emerges in between these uppers and downers is a whole lot of looking. But the photograph can be seeing. It can see—that is in some fuller measure apprehend and understand—what is the case, visible and invisible. This is not because of what photography is, but because of what the world is, and what the photographer is. What is the world? it is visible and invisible, resonant with significance, answering purpose, even. How then shall I see the world? As the world visible and invisible! Given such conditions, can seeing be an exhaustive or total affair? Thank God, no! (total knowing being a bad fantasy, typically only achieved by prior exclusions of what can been known); instead, my seeing is as I am: creaturely and limited—there’s always a white field that bounds my imaging. To be chastened by this is to be released to see things as they’re given me to be seen. And so, it is to have joy.

It was a kind of tender joy in Chris that stayed with me after we met to talk over this project, the fruit maybe of his long attentiveness. Such attentiveness, it seems to me, can give rise to wonder and to love’s work of beholding, while opening us also to the grief of love—the good sadness involved in knowing other people and in knowing a place. These images are from a recent return to Hiruharama. Chris was, it seemed to me, drawn back into attentiveness by a desire to register and perhaps understand something of the mystery of that place and its people—to see it, visible and invisible.

What follows here in words will, I hope, bear witness to the goodness of that desire, and perhaps join and amplify the work of seeing. The number of images (14, with an opening photograph) and the Catholic associations of Hiruharama call to mind the traditional Stations of the Cross, although his sequence avoids any crude parallels, instead returning to ruminate on recurrent motifs: stone, water, boy, here, cross. And then always, there is an excess and ineffable quality to the whole sequence. Something of that ruminating and that ineffable quality is operative in the following meditations, which centre on four words.

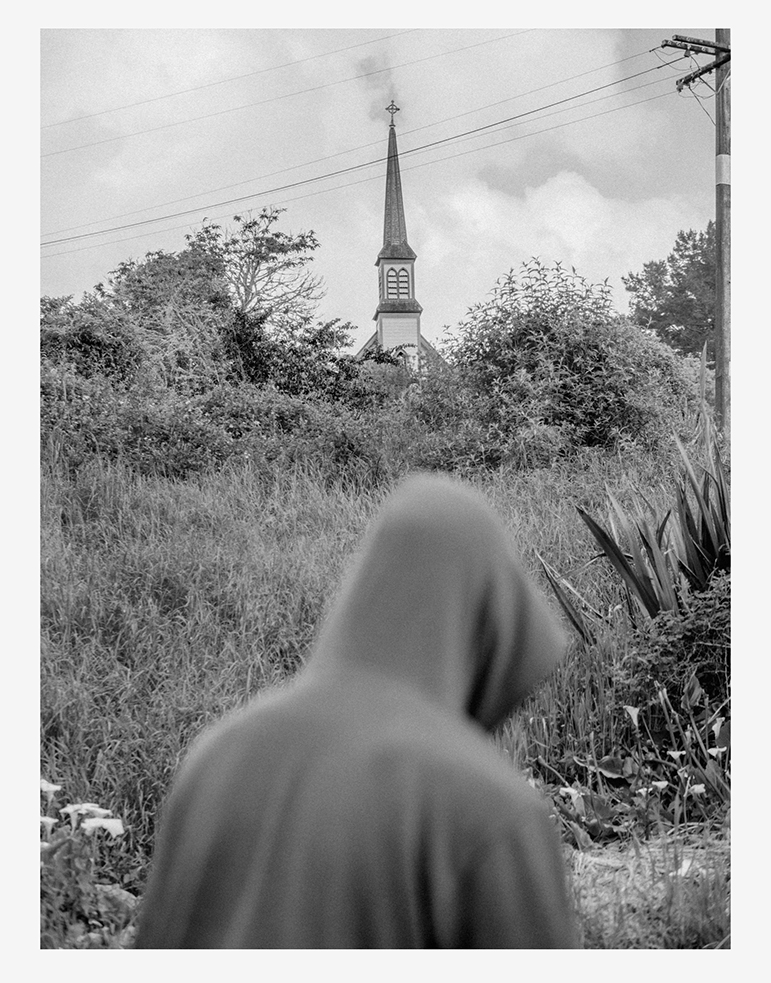

Boy

No choice but to follow him. Up there, the insistent spire with its cross, very slightly off-kilter. But he is moving off, head-down—a boy’s head with a man’s shoulders, and unfocussed. I’m not sure what to aim for here, but there’s no waiting: he’s getting on with it, under the brightness that falls thickly from a diffuse day. It is a kind of summer. The power-pole waits for him, indifferent, crossarms akimbo.

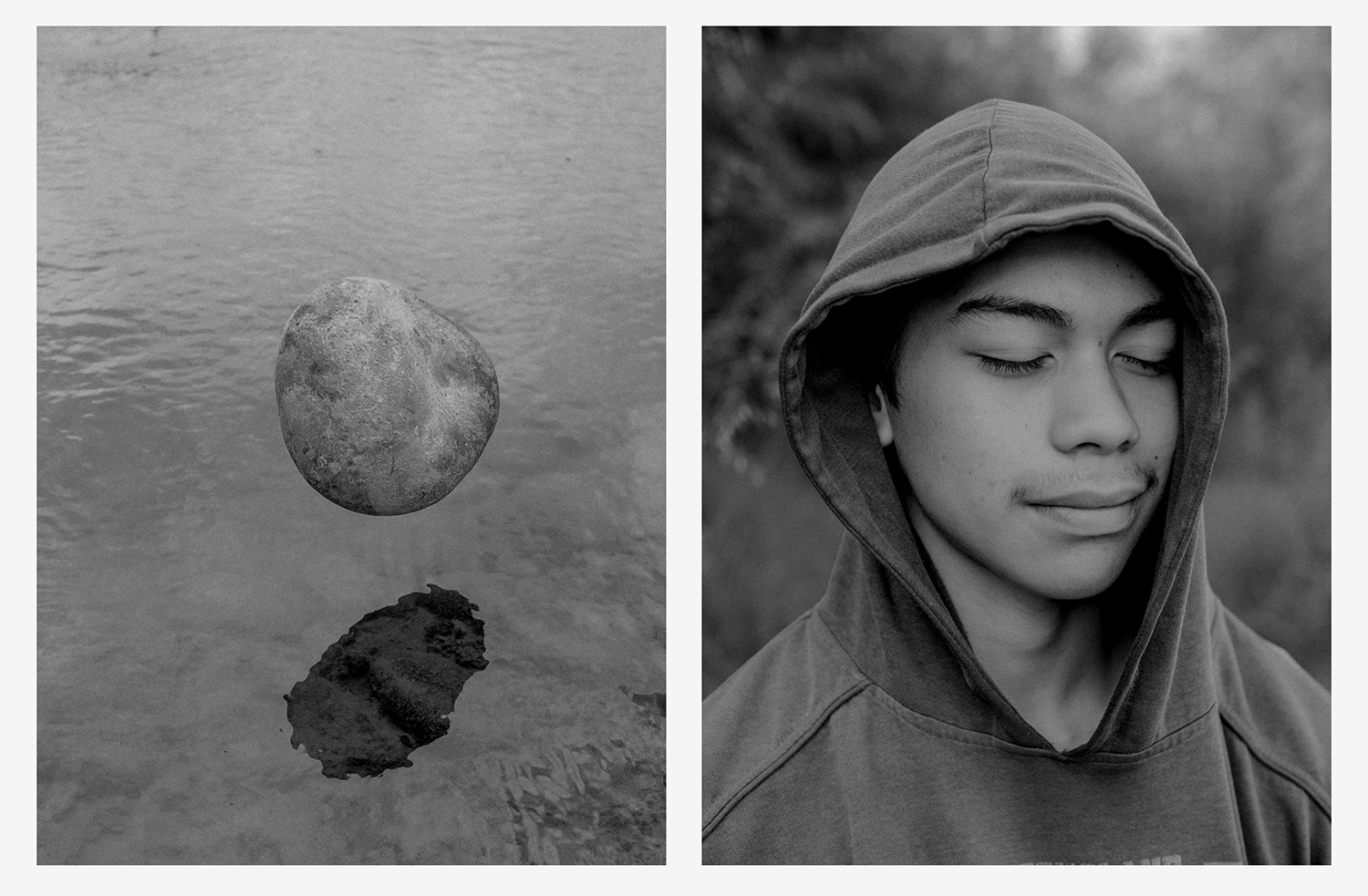

Still following, and it’s not clear where we’re up to, except that a kind of love is at work in the regard for this boy—this boy and not another—who stands at a three-quarter turn, more slight, more definitely himself, the body exceeding our ken just as every face, when it does suddenly turn to us, commands silence.

Do not say ‘captured’. Do not even venture ‘held’, unless it be to own the way in which this face apprehends anyone who sees it: we’re held, our assent compelled by the courtesies of presence. We will not suffer the eyes, will allow the sheltered mystery of this boy to be what it is: irreducibly person. What there is here is strange and mostly unseen: this one, not you. And beautiful: this boy, this boy, this boy. Now, here, an inscrutable joy, settling like a sun-warm stone.

Stone

Far easier, the black ripples widening across the day’s split reflection: bush cuts to skyline rendered in a forgetful moment of dark river. This at least is graspable: this is the momentary place of impact, where the air briefly caught in the stone’s folds of tumble now rises to say, ‘Here. It was here.’ We can get our heads around this, can say, knowingly, ‘This is how it ends’: the random rock, barreling into water—kaboosh!—and from the bridge above the boy’s shout. Stones fall, we affirm. Kaboosh.

There is, of course, much more that might concern us about these widening circles. Let us call them, for instance, the face of the waters, and brood over them, remembering God’s Spirit at the beginning of all things. However uneasy we become with it, this face looks back at us, weighing our concern. What do you see here? Is it mere impact, the place where a stone was inevitably overwhelmed? Or is it death’s comic overturning in a rising rush of air—that is, do you see baptism? The river reads the reader, sees through the viewer.

Still, the water is easier to live with than these stones, which are shocking in their utter now, their simple and relaxed way above the water. There’s no bridge, no boy, no shout, no widening impact—nothing known or inevitable about this apprehended now, which is wild with unexpected trajectory, the stone as likely to rise further or drift on the downstream breeze as to fall. A now so finely sliced, it’s a weird and fey power-play, magic with wrongness. By its difficult ease, it compels.

Difficult, because I may have no index for what I am seeing, no index unless it be our hearts which like stones impossibly hover, holding off from the beginning of all things, refusing baptism by water and by spirit. Ours is a bad dream of lightness, of a levitation of self, a higher plane and ethereal spirituality, of power and ease. It’s this vapid wanting that rises up to agree with the impossible stone, the insistent magical now.

And then it passes. Before the stone kisses the river, before the tumbled air rises, see here now: each one (each stone; each heart) lively with water-birthed detail, already in agreement with its baptismal shadow, rushing to meet it.

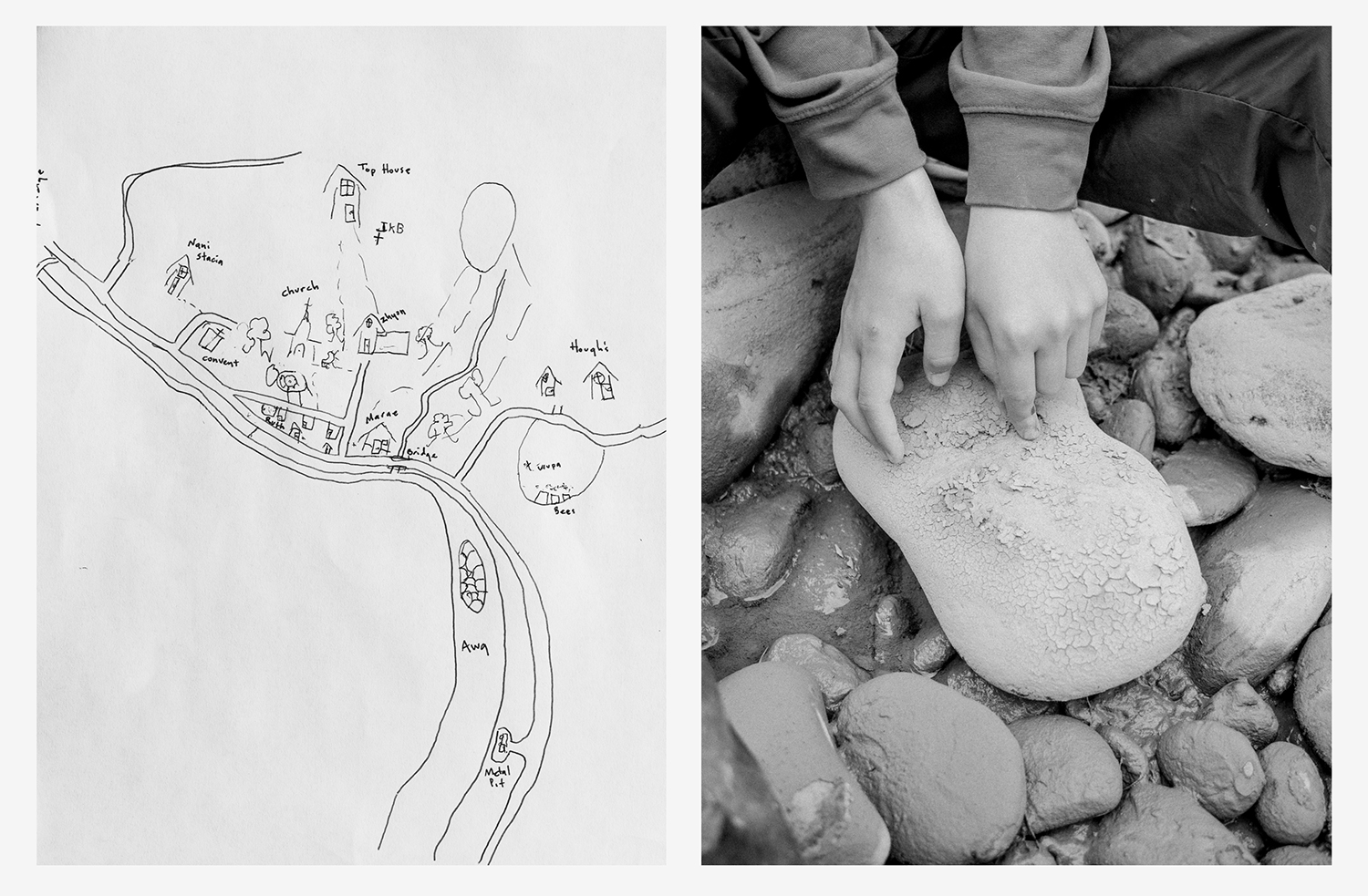

Here

See the map of the North Island Gregory O’Brien once told me of, drawn to indicate spiritual significance: Auckland, Wellington are tiny dots, dwarfed by the real centres, Parihaka, Kopua, Hiruharama, supernovas of the spiritual landscape. However up for grabs this may be (and sure, it needs fuller mapping), it points up what here requires of us, how here requires us to attend to things invisible as well as visible—to attend to those things that might make a place of seeming insignificance or precariousness a centre.

We might, let us say, pay attention to life lived in long agreement with the given features of water and land—or in disagreement with these. We might consider how people live rightly in a place, or fail to do so; to histories of blessing or cursing, of condemnation or forgiveness; to foundational words and actions that are raised like banners over the earth, or become gateways to those coming after (why is it, for instance, that life in Auckland is so prone to acedia—to spiritual inattention? What is the significance for Wellington of the willful inscription on Wakefield’s great slab: “The utmost happiness God vouchsafes to man on earth: the realization of his own idea”?). Etc.

Here, the river flowing, and the hills. Moon settles into the poplars, sings from the utmost like a blackbird at evening as the sky scaffolds makeshift towers about. Trees grow up through hands and go walking. Hills softly undress; the slips are full of it. No frame can take this in, can take in the wet macular of cloud and all it sees, hovering over waters; which is to say all this is here and before, prevenient in-placeness.

And now the boy’s hands this time, reaching for a stone surfacing through the dust. The clay here is so fine. It loves everything it touches, touches everything: the metal pit, urupa, bees, church, Zhyon, Top House. And boulders rush down to be loved and touched: this stone, this stone, this stone. Right here: that’s where you’re being touched—see?

Cross

The Romans did it best (bodies like banners along the Apian Way), but Golgotha ruined all that, the instrument of terror re-purposed as signpost and mercy seat, as the way of baptism. Seen whole, the cross becomes the incision, full of care, at which the heavens and the earth are opened, becomes a precise wound through which each (this boy) can get on with it.

Seen in section, it is lively, the line a stone makes as it falls to the river’s horizon; the line air makes as it rises through dark water from folds of tumble.

No wonder then that it proves so ready to fall apart in the hands of those who take it up as a sword, use it to make a point. McCahon saw this. Saw also its necessity, the cross as load-bearing structure, a way of holding things up—sheds, bridges, wires. The cross is the original power-pole, all crossarms and singing lines—basic infrastructure.

Not startled, then, by the unfinished studwork in the shed, the place of killing. That is the place through which this line of thought leads: into Pilate’s atrium, the cool of the courtyard always just beyond, with the sun on untold branches, and birdsong beginning again around Jesus’ silence.

Darkly, the horizon and the water rippling out; the incision, full of care; crossarms and powerlines, over shoulders like a stone rolling; basic infrastructure, holding up the roof, right here.

John Dennison is a poet. He is the author of ‘Otherwise’ (AUP/Carcanet, 2015), and a critical monograph, ‘Seamus Heaney and the Adequacy of Poetry’ (Oxford, 2015). He lives in Tawa, Wellington.

Footnote

[1] See Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007).